Study Notes

Overview

This topic, Energy, is a cornerstone of your GCSE Combined Science course. It explores the fundamental principle that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transferred from one store to another. Understanding this concept is crucial, as it underpins many other areas of physics, from electricity to mechanics. In the exam, you will be expected to precisely identify different energy stores, describe how energy is transferred between them, and perform calculations involving kinetic energy, potential energy, and power. AQA examiners place a strong emphasis on using correct scientific terminology, so mastering the language of energy is just as important as mastering the equations. Expect a mix of calculation questions, descriptive tasks, and evaluations of energy resources. A solid grasp of this topic will give you the confidence to tackle a significant portion of your physics papers.

Key Concepts

1. Energy Stores and Systems

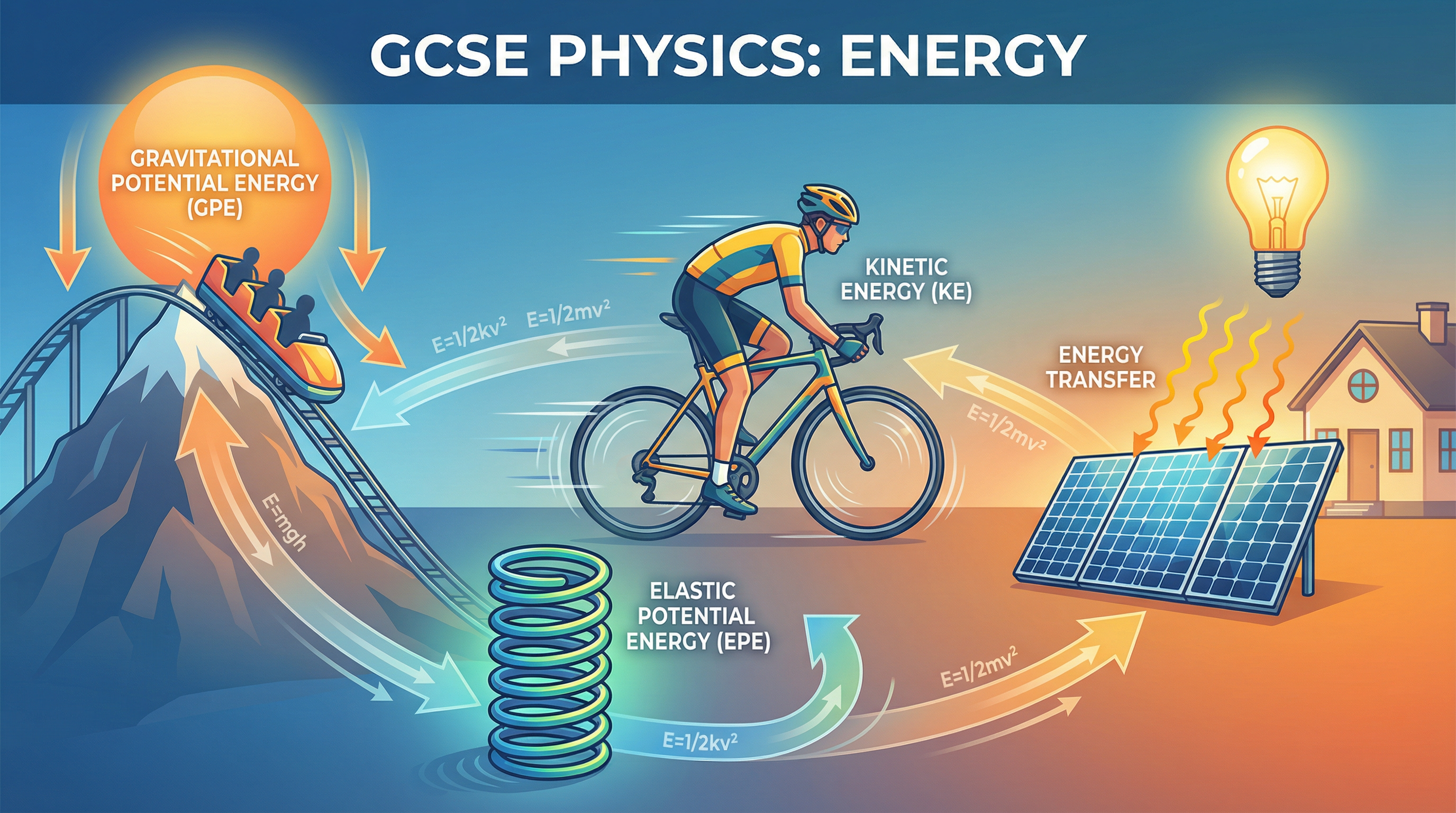

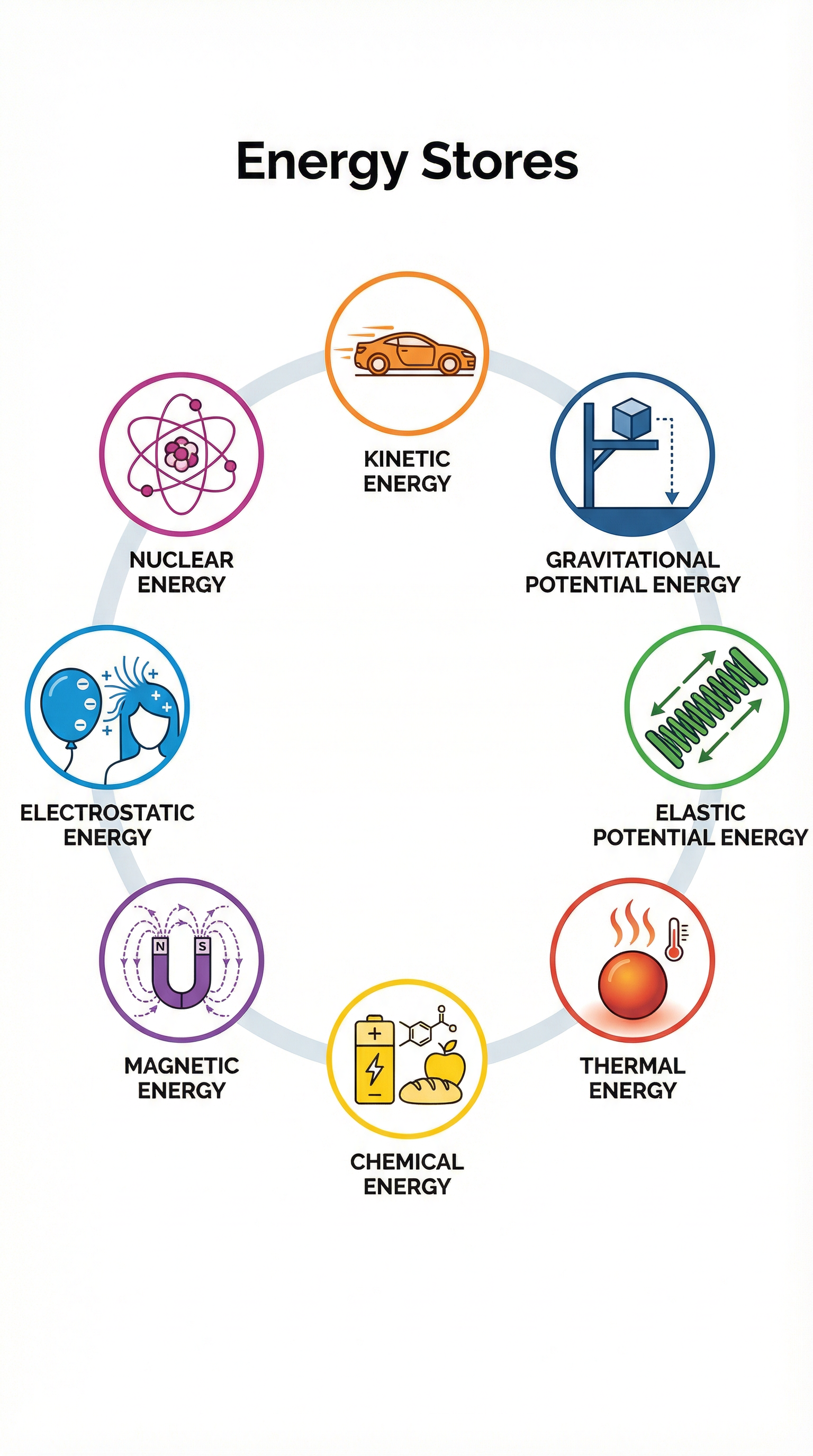

In physics, we think of energy as being held in different stores. An object or a group of objects is called a system, and we analyze how energy is stored within that system. For your AQA exam, you must be familiar with eight distinct energy stores. Using these precise terms is essential for gaining marks.

The eight energy stores are kinetic energy, which is the energy of a moving object—the faster it moves or the more mass it has, the larger its kinetic energy store; gravitational potential energy, the energy stored in an object due to its position in a gravitational field, where the higher it is, the more GPE it has; elastic potential energy, the energy stored in a stretched or compressed object like a spring or rubber band; thermal energy, the total kinetic and potential energy of particles within an object, where hotter objects have more thermal energy; chemical energy, stored in the bonds between atoms and released during chemical reactions in substances like food, fuel, and batteries; magnetic energy, stored when repelling poles have been pushed closer together or attracting poles pulled further apart; electrostatic energy, stored when repelling charges have been moved closer or attracting charges pulled further apart; and nuclear energy, stored in the nucleus of an atom and released during nuclear reactions.

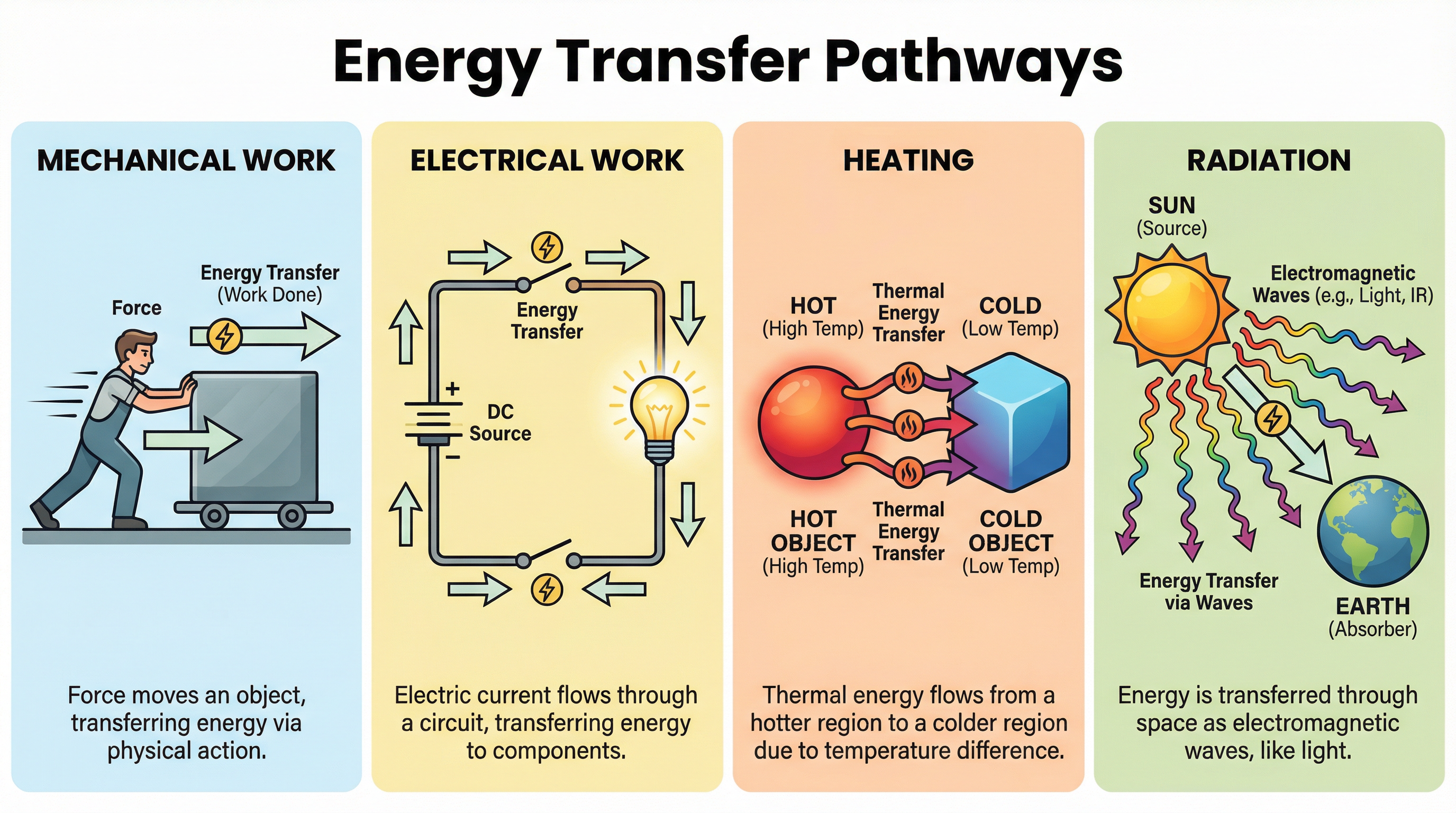

2. Energy Transfers (Pathways)

Energy is moved from one store to another via one of four transfer pathways. When describing an energy change, you must state the initial store, the pathway, and the final store.

The four pathways are mechanical work, where a force moves an object through a distance—for example, when you push a box, you are doing mechanical work, transferring energy from your chemical store to the box's kinetic store. Electrical work occurs when charges move due to a potential difference (voltage), which is how energy is transferred in an electrical circuit. Heating transfers energy from a hotter object to a colder object, such as when a hot drink transfers energy by heating to the cooler surroundings. Radiation transfers energy by waves, such as light or sound—the Sun transfers energy to the Earth via electromagnetic radiation.

For example, when a ball is thrown upwards, the chemical energy store in your muscles is transferred via mechanical work to the kinetic energy store of the ball. As the ball rises, its kinetic energy store decreases while its gravitational potential energy store increases. At its peak, the GPE store is at its maximum.

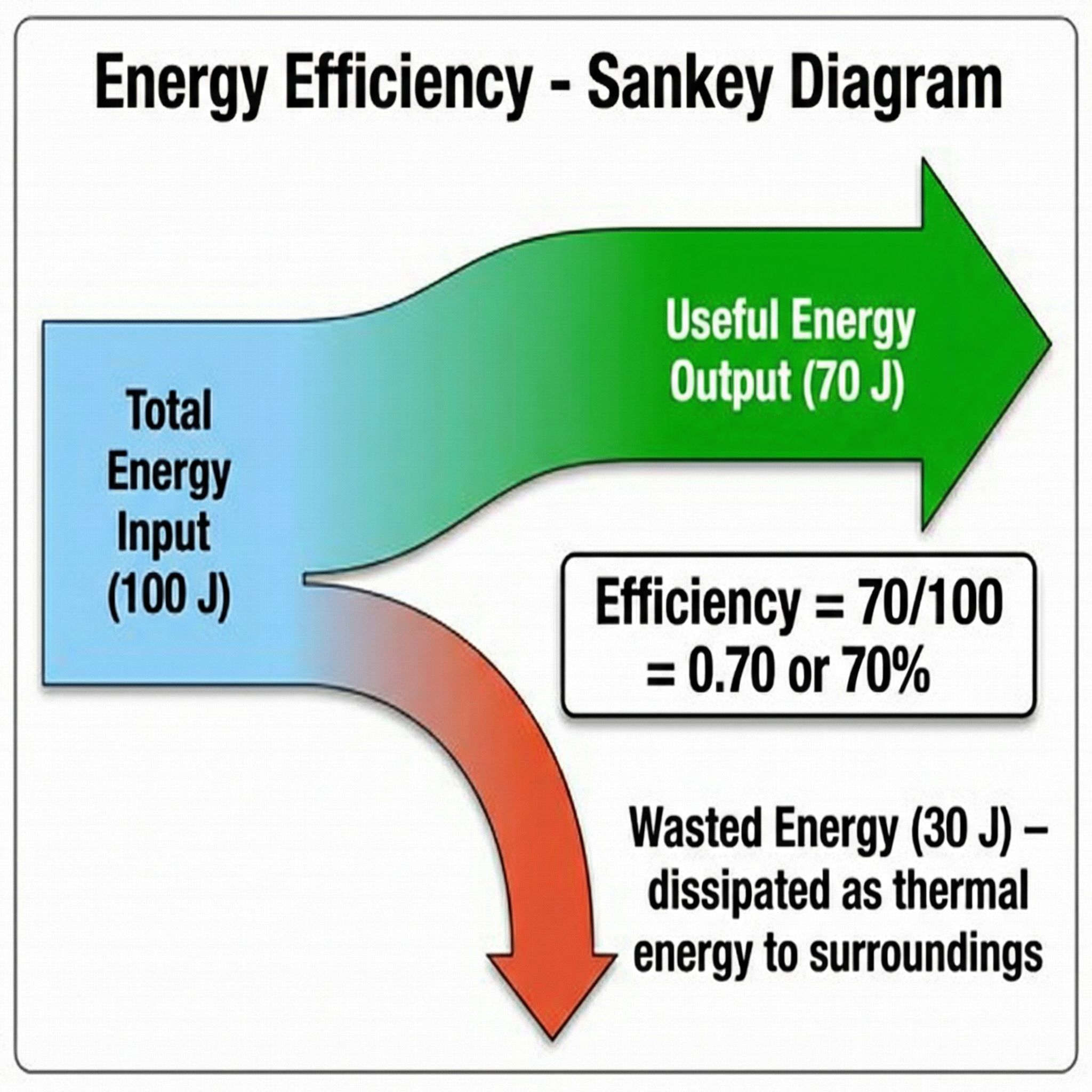

3. Conservation of Energy

This is the most important principle in this topic: Energy can be transferred usefully, stored, or dissipated, but it cannot be created or destroyed. The total amount of energy in a closed system remains constant. However, not all energy transfers are useful. When you use a device, you want it to perform a specific job. The energy transferred to achieve this is the useful energy. Any other energy transfers are considered wasted energy. Wasted energy is often dissipated (spread out) into the surroundings, increasing their thermal energy store. For example, the useful energy transfer in a light bulb is to its light radiation store, but a lot of energy is wasted by heating the bulb and the air around it.

4. Efficiency

Efficiency is a measure of how good a device is at transferring energy into a useful form. A more efficient device wastes less energy.

Efficiency can be calculated using the following equations: Efficiency = Useful output energy transfer ÷ Total input energy transfer, or alternatively, Efficiency = Useful power output ÷ Total power input. Efficiency is a ratio and has no units. It can be expressed as a decimal (e.g., 0.75) or a percentage (e.g., 75%). No device is 100% efficient.

Mathematical Relationships

Examiners will expect you to recall and apply several key formulas. You must show your working in calculations to secure method marks.

1. Kinetic Energy (KE)

- Formula: Ek = ½ × m × v²

- Must memorise

- Ek = Kinetic Energy (Joules, J)

- m = mass (kilograms, kg)

- v = speed (metres per second, m/s)

- Key point: The speed is squared (v²). This means doubling the speed quadruples the kinetic energy.

2. Gravitational Potential Energy (GPE)

- Formula: Ep = m × g × h

- Given on formula sheet

- Ep = Gravitational Potential Energy (Joules, J)

- m = mass (kilograms, kg)

- g = gravitational field strength (Newtons per kilogram, N/kg). On Earth, this is approximately 9.8 N/kg.

- h = height (metres, m)

3. Elastic Potential Energy (EPE)

- Formula: Ee = ½ × k × e²

- Given on formula sheet

- Ee = Elastic Potential Energy (Joules, J)

- k = spring constant (Newtons per metre, N/m). This measures the stiffness of the spring.

- e = extension (metres, m)

- Key point: The extension is squared (e²).

4. Power

- Formula: P = E ÷ t

- Given on formula sheet

- P = Power (Watts, W)

- E = Energy transferred (Joules, J)

- t = time (seconds, s)

Required Practical: Thermal Insulation

This practical investigates the effectiveness of different materials as thermal insulators. The apparatus includes beakers, a kettle, thermometer, insulating materials (such as bubble wrap, cotton wool, or foil), a stopwatch, and lids. The method involves boiling water in a kettle and pouring the same volume of hot water into several identical beakers. You measure the initial temperature of the water in each beaker, then wrap each beaker in a different insulating material, leaving one beaker unwrapped as a control. Place a lid on each beaker to reduce energy loss from the surface, start a stopwatch, and record the temperature of the water in each beaker every three minutes for fifteen minutes.

The expected results show that the beaker with the most effective insulator will show the smallest temperature drop over the fifteen-minute period, while the control beaker will cool the fastest. Common errors include using different volumes of water, not using a lid, and reading the thermometer incorrectly due to parallax error. Examiners may ask you to describe the method, identify variables (independent: insulator type; dependent: temperature change; control: volume of water, starting temperature), or interpret results from a table or graph.