Study Notes

Overview

This topic forms the foundation of classical mechanics, bridging the descriptive kinematics of how objects move with the dynamic forces that cause this motion. A thorough grasp of this area is crucial for success in the Physics component of the Edexcel GCSE Combined Science exam. You will be expected to be fluent in the language of motion, distinguishing between vector and scalar quantities, interpreting graphical representations of motion, and applying Newton's three laws to a variety of real-world and abstract scenarios. Exam questions frequently test mathematical fluency, requiring you to rearrange and solve equations like F=ma and those for uniform acceleration. This guide will equip you with the conceptual understanding and practical skills to tackle these questions with confidence.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Scalar and Vector Quantities

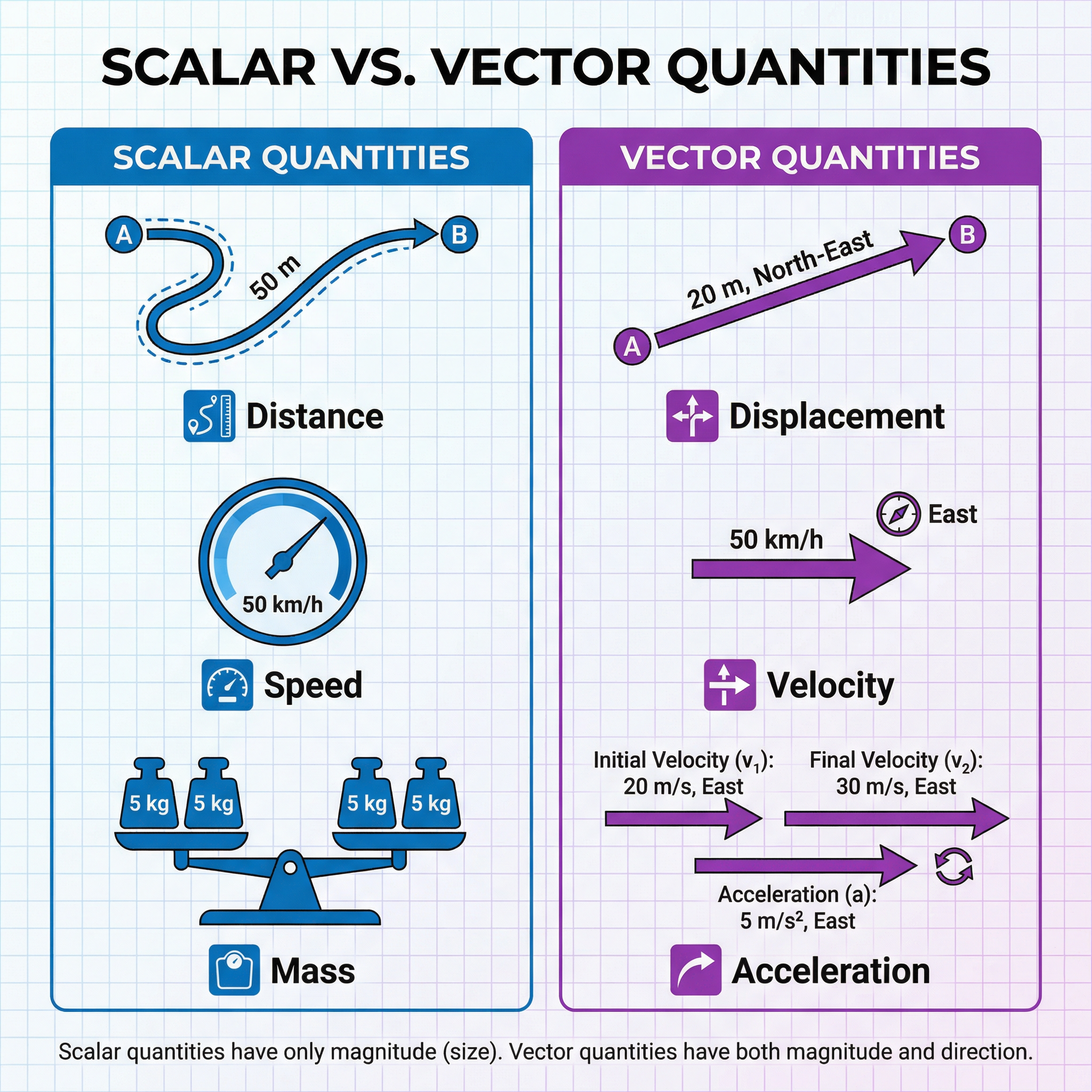

In physics, every quantity you measure is either a scalar or a vector. This is a fundamental distinction that you must be comfortable with. A scalar quantity has only magnitude (a size or amount). A vector quantity has both magnitude and direction.

- Scalar Examples: Distance (e.g., 50 m), Speed (e.g., 20 m/s), Mass (e.g., 10 kg), Time, Temperature, Energy.

- Vector Examples: Displacement (e.g., 50 m North), Velocity (e.g., 20 m/s East), Acceleration (e.g., 9.8 m/s² downwards), Force (e.g., 100 N upwards), Momentum.

Why it matters: Examiners often set questions to trap candidates who confuse these. For example, an object that travels in a complete circle may have covered a large distance, but its final displacement is zero.

Concept 2: Motion Graphs

Graphs are a powerful way to represent an object's motion. You need to be able to interpret both distance-time and velocity-time graphs.

Distance-Time Graphs

- The gradient (steepness) of the line represents the speed.

- A horizontal line means the object is stationary (speed = 0).

- A straight, diagonal line means the object is moving at a constant speed.

- A curved line indicates that the speed is changing (acceleration or deceleration).

Velocity-Time Graphs

- The gradient of the line represents acceleration.

- The area under the graph represents the distance travelled (or displacement).

- A horizontal line means the object is moving at a constant velocity (acceleration = 0).

- A straight, diagonal line means the object is moving with constant acceleration.

- A line with a negative gradient means the object is decelerating.

Concept 3: Newton's Laws of Motion

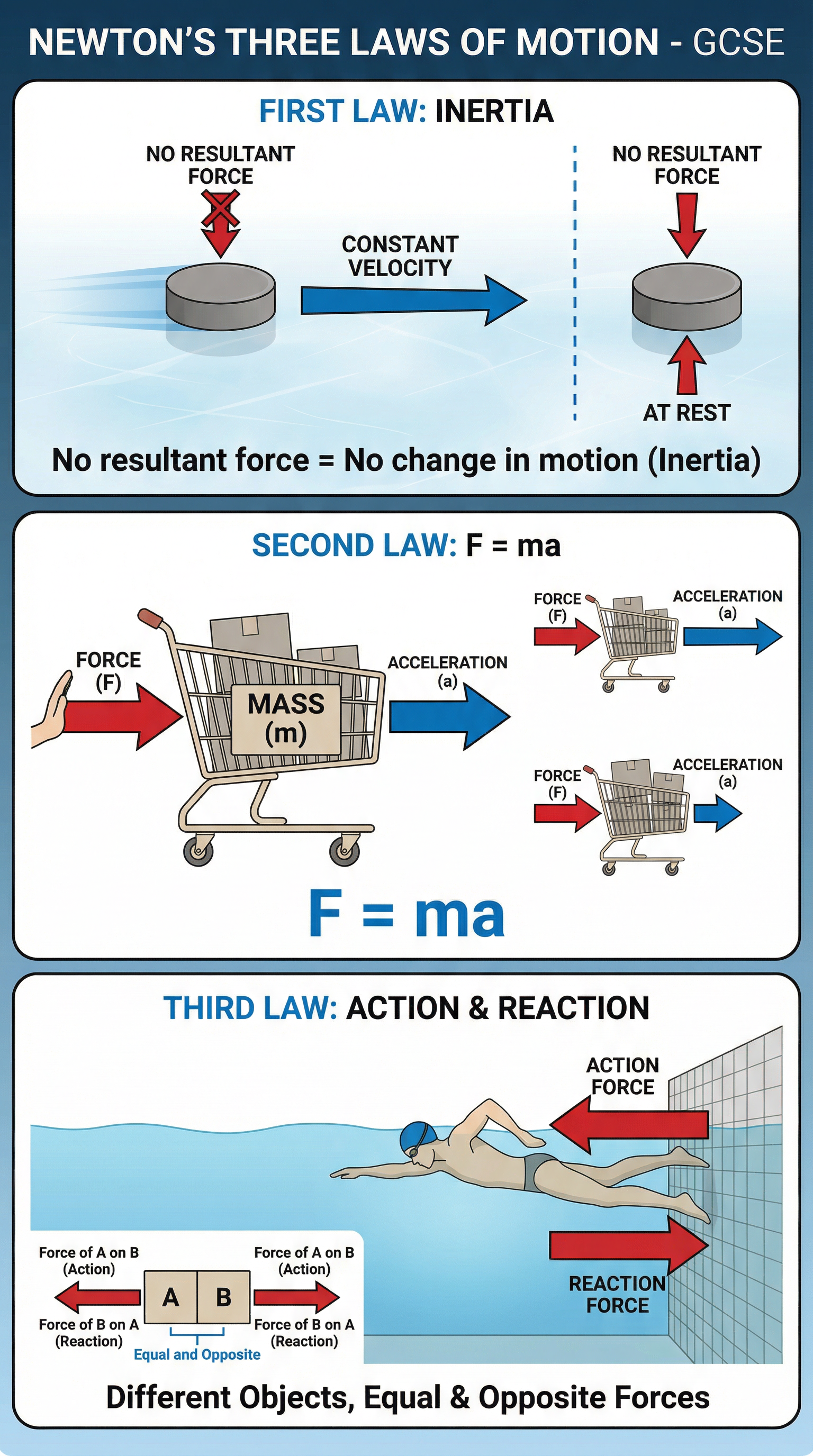

Sir Isaac Newton's three laws are the bedrock of dynamics. They explain why objects move in the way they do.

-

Newton's First Law (The Law of Inertia): An object will remain at rest or continue to move at a constant velocity unless acted upon by a resultant force. In simple terms, things keep doing what they're doing unless you push or pull them. An object's reluctance to change its state of motion is called inertia.

-

Newton's Second Law: The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the resultant force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass. This is summed up in the most important equation in this topic: Force = mass × acceleration (F = ma). This means a larger force produces a larger acceleration, while a larger mass results in a smaller acceleration for the same force.

-

Newton's Third Law: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. This means that forces always come in pairs. If object A exerts a force on object B, then object B exerts an equal and opposite force on object A. Crucially, these two forces act on different objects and are of the same type (e.g., both gravitational or both contact forces).

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

You must be confident using the following equations:

- Speed (scalar):

speed = distance / time(Must memorise) - Velocity (vector):

velocity = displacement / time(Must memorise) - Acceleration (vector):

acceleration = change in velocity / time takenora = (v - u) / t(Given on formula sheet) - Newton's Second Law:

Resultant Force = mass × accelerationorF = ma(Given on formula sheet) - (Higher Tier Only) Final Velocity Squared:

(final velocity)² - (initial velocity)² = 2 × acceleration × distanceorv² - u² = 2ax(Given on formula sheet) - Weight:

Weight = mass × gravitational field strengthorW = mg(Given on formula sheet)

Unit Conversions: A common source of lost marks is failing to convert units. Always convert to standard SI units before calculating:

- Mass: grams (g) to kilograms (kg) -> divide by 1000

- Time: minutes (min) to seconds (s) -> multiply by 60

- Speed/Velocity: kilometres per hour (km/h) to metres per second (m/s) -> divide by 3.6 (or multiply by 1000 and divide by 3600).

Practical Applications

Core Practical: Investigate the relationship between force, mass and acceleration by investigating the effect of varying the force on the acceleration of an object of constant mass and the effect of varying the mass of an object on the acceleration produced by a constant force.

Apparatus: Trolley, runway, set of masses, pulley, string, timer/light gates, metre ruler.

Method (Varying Force):

- Set up the apparatus with the trolley on the runway, connected by a string to a mass holder hanging over a pulley.

- The total mass of the system (trolley + masses on it) is kept constant.

- The force is varied by moving masses from the trolley to the mass holder. The force is the weight of the mass holder and its masses (F = mg).

- Release the trolley and measure the time it takes to travel a fixed distance. Calculate acceleration using an appropriate equation (e.g., from

s = ut + ½at²if starting from rest, or by using light gates to measure initial and final velocity). - Repeat for a range of different forces.

Expected Results: A graph of acceleration (y-axis) against force (x-axis) should be a straight line through the origin, showing that acceleration is directly proportional to the resultant force.

Common Errors: Friction between the trolley and the runway can affect the results. This can be minimised by tilting the runway slightly until the trolley just begins to roll on its own, compensating for the frictional force.

Terminal Velocity

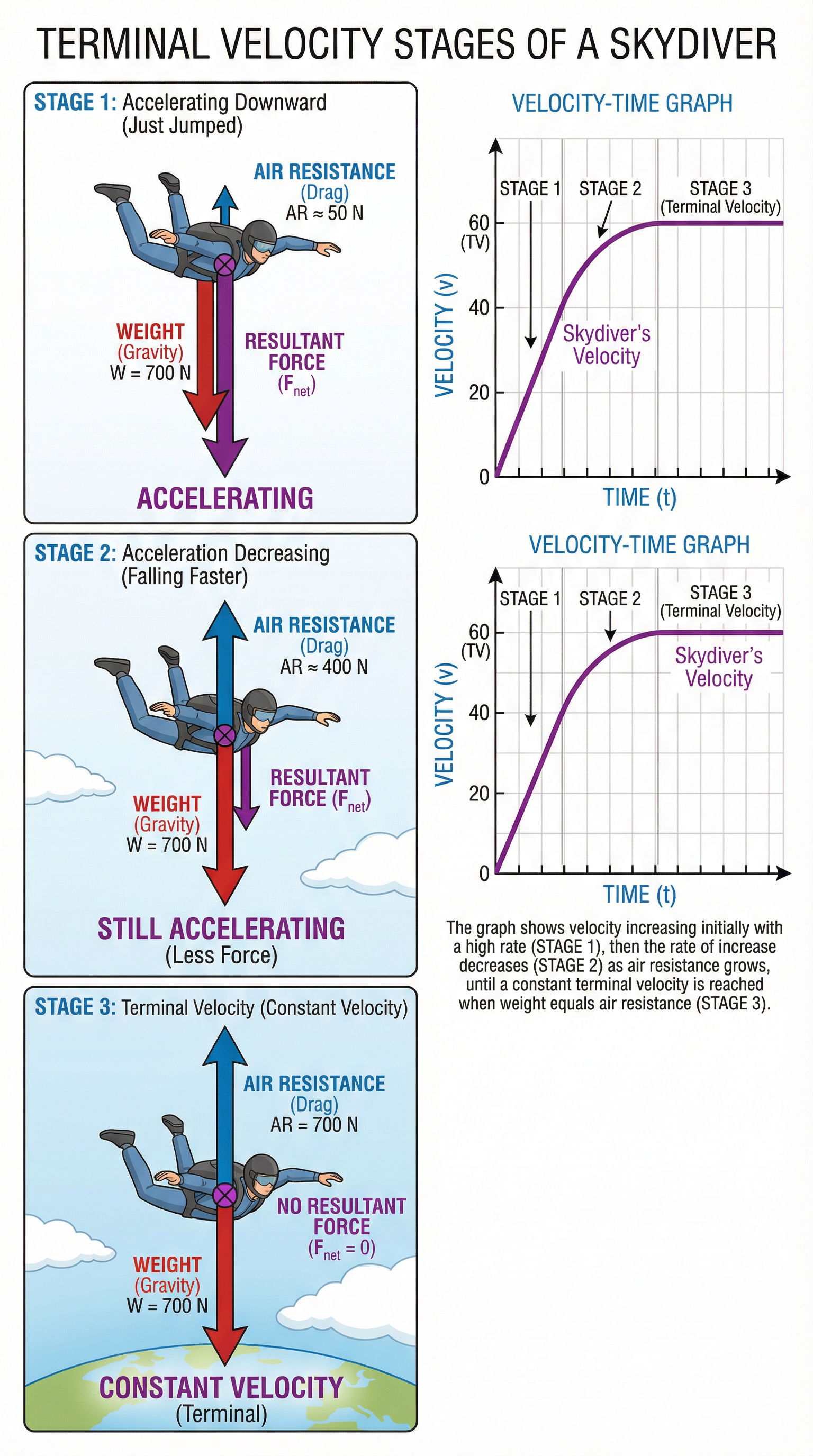

This is a real-world application of Newton's laws. When a skydiver jumps out of a plane:

- Initially, the only significant force is weight (due to gravity). The resultant force is large and downwards, so the skydiver accelerates rapidly.

- As velocity increases, air resistance (a type of friction) increases. This force acts upwards, opposing the weight.

- The resultant force (Weight - Air Resistance) decreases, so the rate of acceleration slows.

- Eventually, the skydiver reaches a speed where the upward force of air resistance becomes equal in size to the downward force of weight. The forces are now balanced, the resultant force is zero, and there is no more acceleration. The skydiver falls at a constant maximum speed, known as terminal velocity.