Study Notes

Overview

This guide covers Rates of Reaction and Energy Changes, a fundamental topic in your Edexcel GCSE Combined Science exam. Mastering this area is crucial as it links to many other parts of the specification and frequently appears in higher-mark questions. We will explore why reactions happen at different speeds, how to measure and calculate their rates, and the critical role of energy in all chemical changes. You will learn to apply Collision Theory to explain how factors like temperature and concentration affect reaction rates, a skill examiners specifically look for. Furthermore, we will dissect reaction profile diagrams to understand activation energy, and distinguish between exothermic and endothermic processes. This topic is not just about memorising facts; it's about applying concepts to unfamiliar contexts, a key AO2 skill. Expect to see questions involving graph interpretation, practical skills, and multi-step calculations.

Key Concepts

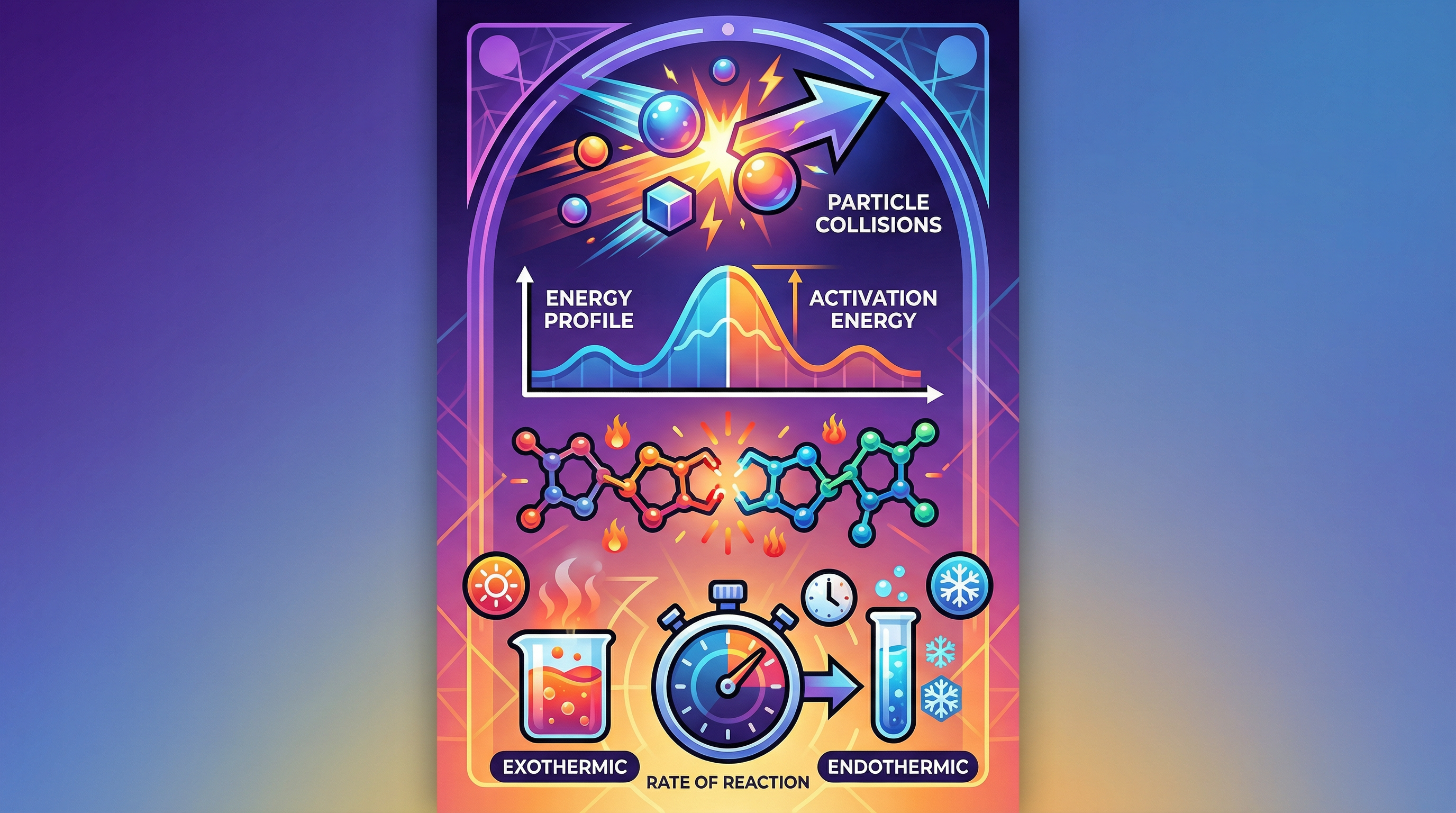

1. Collision Theory

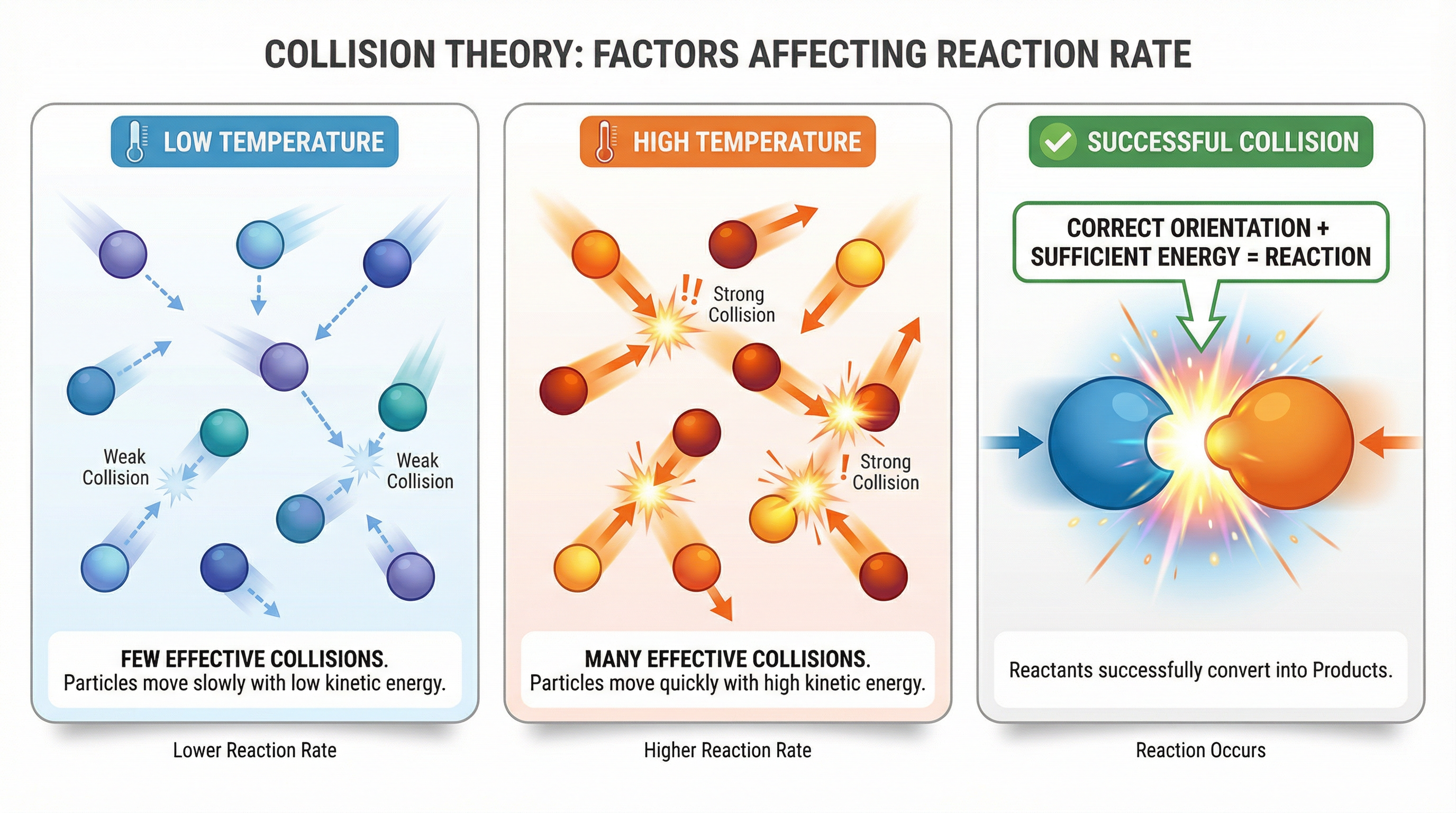

Collision Theory is the bedrock for understanding reaction rates. For a chemical reaction to occur, reactant particles must collide with each other. However, not all collisions lead to a reaction. A successful, or effective, collision requires two key conditions to be met:

- Sufficient Energy: The colliding particles must have a minimum amount of kinetic energy, known as the activation energy (Ea).

- Correct Orientation: The particles must collide in the correct spatial arrangement for bonds to be broken and new bonds to be formed.

Think of it like a key fitting into a lock. The key (one particle) must not only have enough force (energy) to turn, but it must also be inserted in the correct orientation to engage the pins (atoms).

Examiners will expect you to use this theory to explain observations, not just state it. The rate of a reaction depends on the frequency of successful collisions. Any factor that increases the frequency of these effective collisions will increase the rate of reaction.

2. Factors Affecting the Rate of Reaction

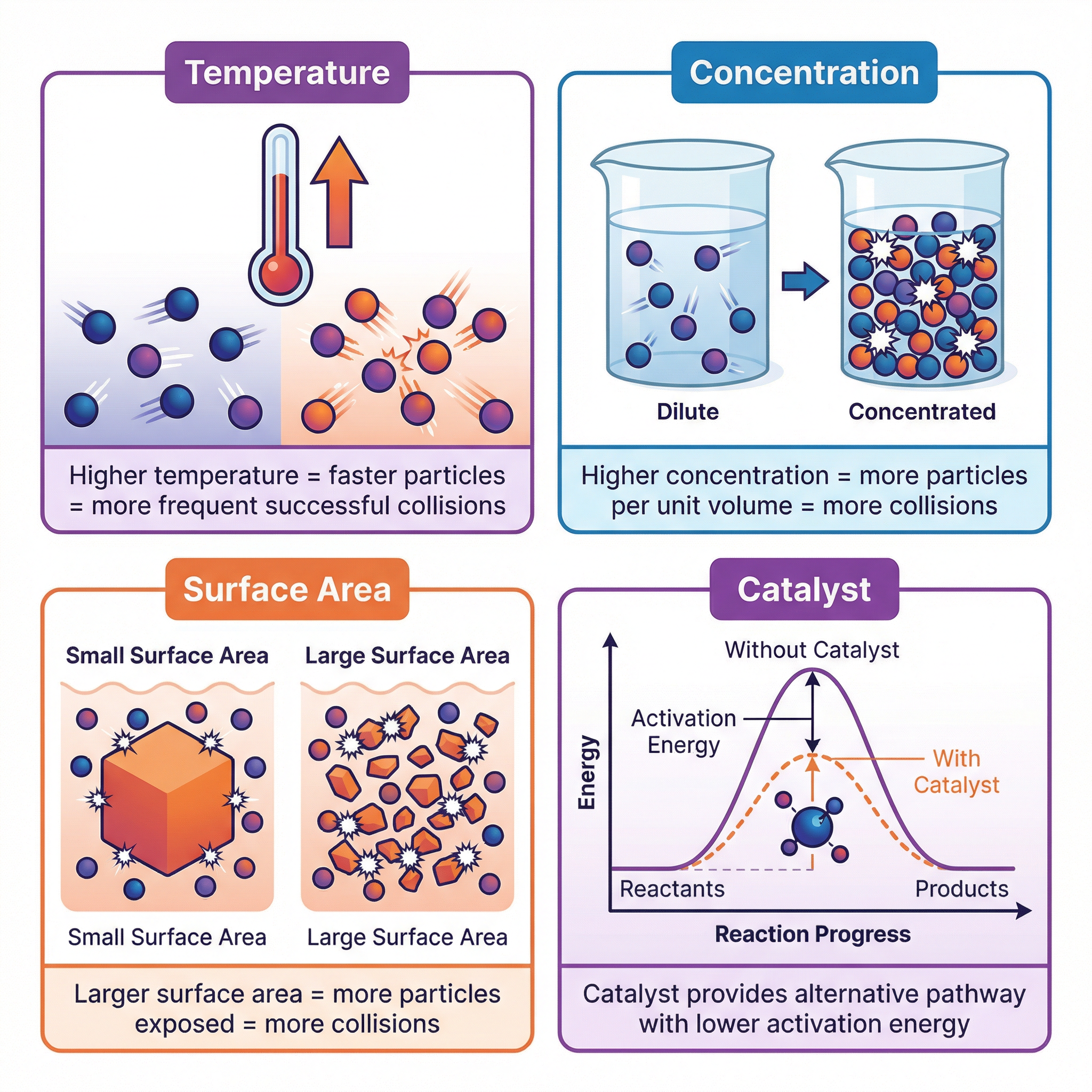

There are four main factors you need to know that affect the rate of a reaction. For your exam, you must be able to explain how each factor alters the rate using the principles of collision theory.

- Temperature: Increasing the temperature gives particles more kinetic energy. This has two effects: the particles move faster, leading to more frequent collisions, and a greater proportion of the collisions will have energy equal to or greater than the activation energy, meaning more collisions are successful. Both factors increase the reaction rate. A common rule of thumb is that a 10°C increase in temperature approximately doubles the rate of reaction.

- Concentration (or Pressure for gases): Increasing the concentration of a reactant in a solution means there are more reactant particles in the same volume. This leads to more frequent collisions between reactant particles, thereby increasing the rate of reaction. It does not change the energy of the collisions, only the frequency.

- Surface Area: This is relevant for reactions involving a solid. If you have a solid lump, only the particles on the surface are available to react. By breaking the solid into a powder, you dramatically increase its surface area. This exposes more particles to the other reactant, leading to more frequent collisions and a faster reaction rate.

- Catalysts: A catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a reaction without being chemically changed itself at the end of the reaction. Catalysts work by providing an alternative reaction pathway with a lower activation energy. This means that at the same temperature, a much larger proportion of collisions will have sufficient energy to be successful. Catalysts do not get used up and are crucial in many industrial processes to save energy and costs.

3. Measuring Rates of Reaction

The rate of reaction can be found by measuring the amount of a reactant used up or the amount of a product formed over time. The formula is:

Rate of Reaction = (Amount of reactant used or product formed) / TimeCommon units for the rate of reaction are g/s, cm³/s, or mol/s. In exams, you will often be asked to calculate the rate from a graph. The gradient (steepness) of the line represents the rate of reaction. The steeper the line, the faster the reaction. To find the rate at a specific point in time, you must draw a tangent to the curve at that point and calculate its gradient (change in y / change in x).

4. Energy Changes in Reactions (Exothermic and Endothermic)

All chemical reactions involve an energy change. This is because energy is required to break existing chemical bonds, and energy is released when new chemical bonds are formed.

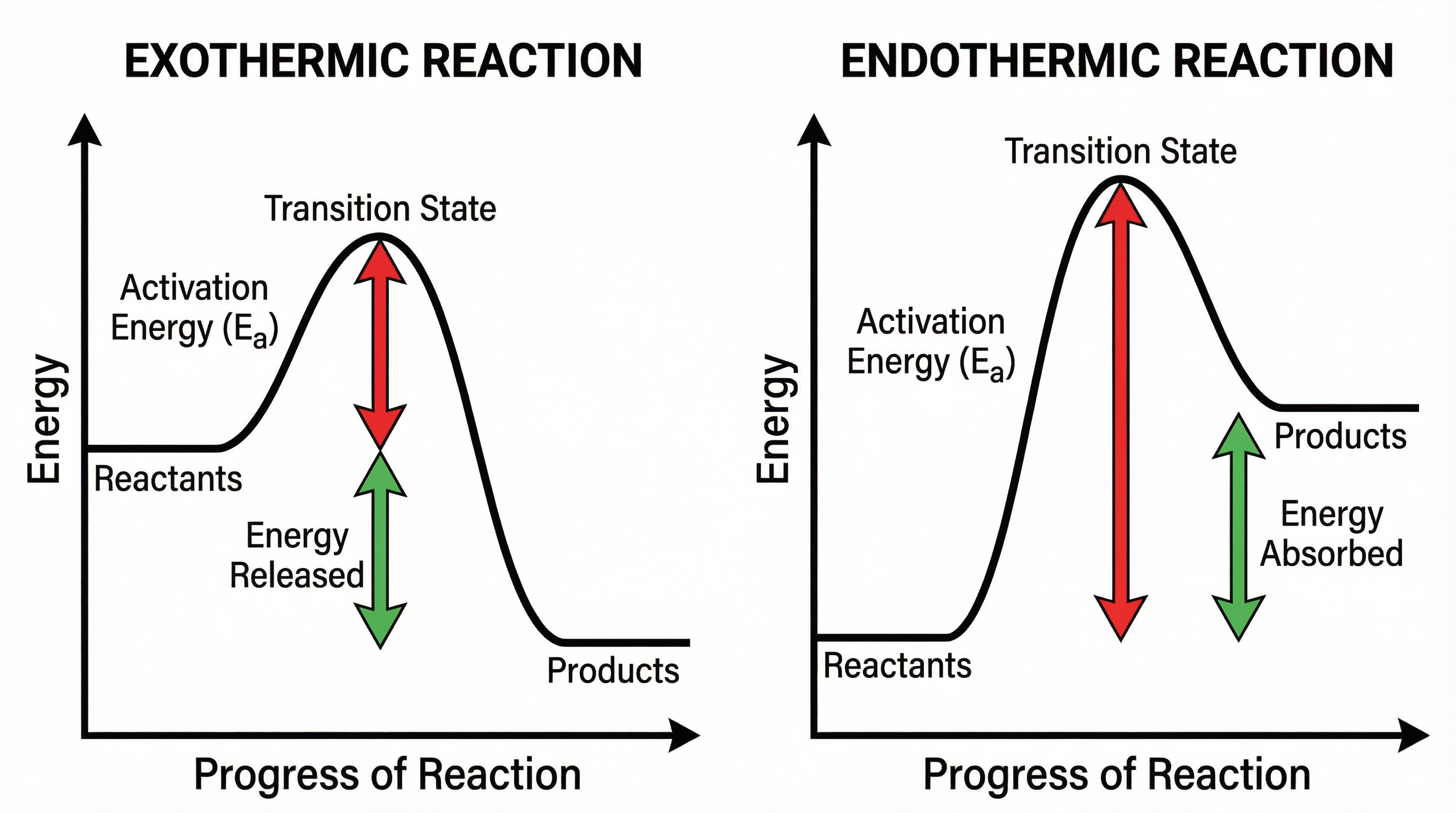

- Exothermic Reactions: In an exothermic reaction, more energy is released when forming new bonds in the products than is required to break the bonds in the reactants. The overall result is a release of energy to the surroundings, which usually get hotter. Combustion and neutralisation are classic examples.

- Endothermic Reactions: In an endothermic reaction, more energy is required to break the bonds in the reactants than is released when forming new bonds in the products. The overall result is an absorption of energy from the surroundings, which usually get colder. Thermal decomposition is a key example.

5. Reaction Profiles

A reaction profile is a diagram that shows the energy of the reactants and products, and the energy change during the course of a reaction. Key features to identify are:

- Reactants and Products: The starting and ending energy levels.

- Activation Energy (Ea): The energy "hump" that must be overcome. It is the difference in energy between the reactants and the transition state (the peak of the hump). Crucially, the arrow must start from the reactants' energy level.

- Overall Energy Change (ΔH): The difference in energy between the reactants and the products. For exothermic reactions, ΔH is negative. For endothermic reactions, ΔH is positive.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

1. Calculating Rate from a Graph

Rate = Gradient of the tangent = (Change in Y-axis) / (Change in X-axis)

- This is a skill you must memorise and be able to apply.

2. Bond Energy Calculations

Overall Energy Change (ΔH) = Σ (Bond energies of bonds broken) - Σ (Bond energies of bonds formed)

- Σ means "sum of".

- Breaking bonds is an endothermic process (energy in).

- Making bonds is an exothermic process (energy out).

- A negative ΔH value indicates an exothermic reaction.

- A positive ΔH value indicates an endothermic reaction.

- Bond energy values will be given on the exam paper; you do not need to memorise them.

Practical Applications

Required Practical: Investigating the Effect of Concentration on Reaction Rate

This is a classic experiment you must know. A common method is the reaction between sodium thiosulfate and hydrochloric acid, which produces a solid precipitate of sulfur, making the solution cloudy.

Method:

- Measure a set volume of sodium thiosulfate solution into a conical flask.

- Place the flask on a piece of paper with a black cross drawn on it.

- Add a set volume of hydrochloric acid to the flask, start a stopwatch immediately, and swirl the flask.

- Look down through the top of the flask and stop the stopwatch when the cross is no longer visible.

- Record the time taken.

- Repeat the experiment using different concentrations of sodium thiosulfate solution, but keeping the total volume of the solution constant by adding water.

Control Variables:

- Concentration of hydrochloric acid

- Total volume of the reaction mixture

- Temperature of the solutions

Expected Results: As the concentration of sodium thiosulfate increases, the time taken for the cross to disappear decreases. This shows that a higher concentration leads to a faster rate of reaction.

Examiner Tip: For 6-mark questions on this practical, you must describe the method logically, state the control variables and explain why they are controlled, and describe how to obtain the results accurately.