Study Notes

Overview

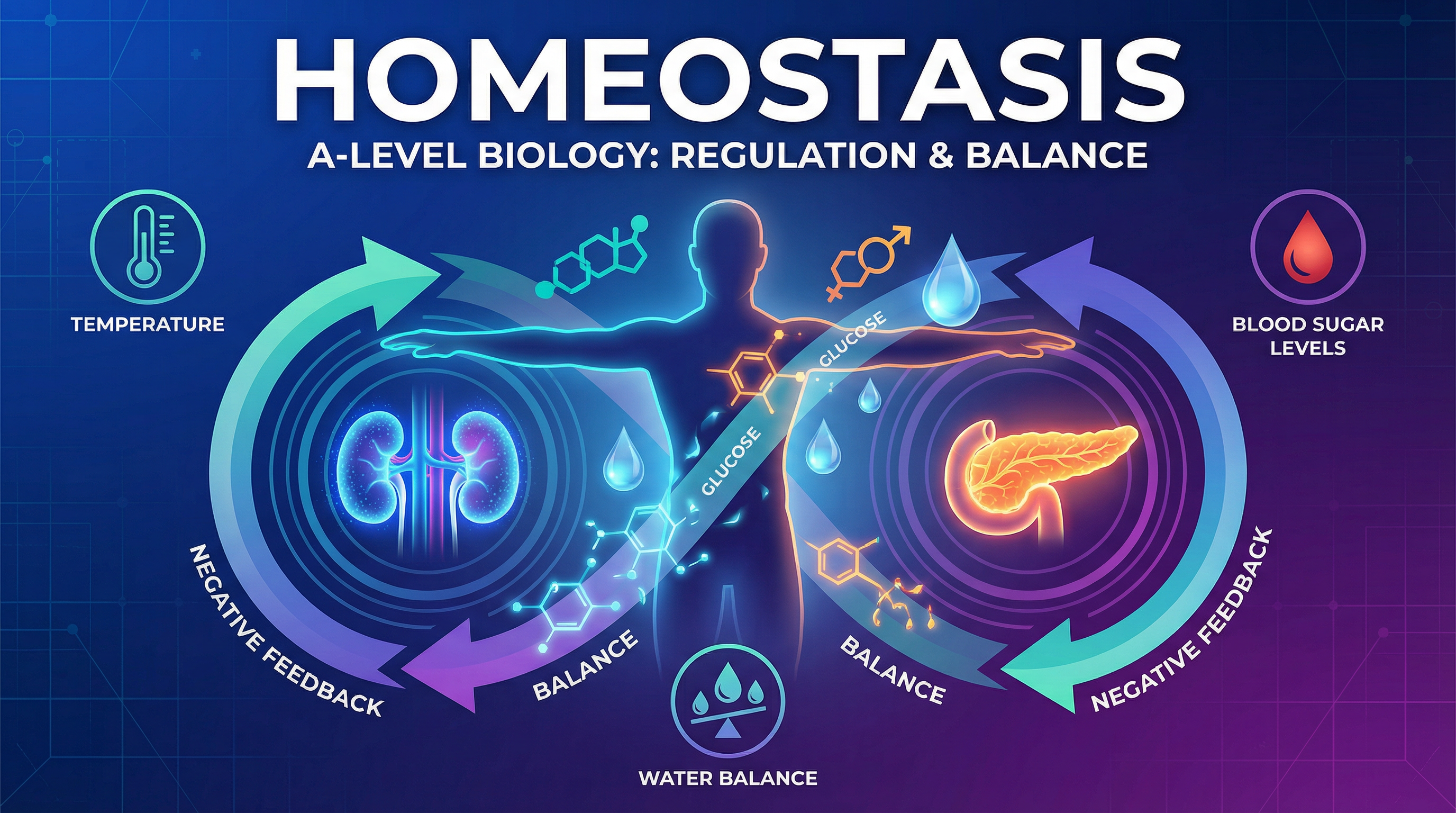

Homeostasis is the maintenance of a stable internal environment in an organism, despite changes in the external or internal conditions. For A-Level candidates, this topic is crucial as it underpins much of physiology and links to numerous other areas of the specification, such as cell biology, enzymes, and coordination. AQA typically assesses homeostasis through two key examples: the regulation of blood glucose concentration and the osmoregulation of the blood, which involves the kidney. Exam questions often require candidates to apply their knowledge to unfamiliar scenarios, interpret data from graphs, and explain complex feedback mechanisms. A strong understanding of negative feedback is essential for achieving high marks, as is the precise use of scientific terminology, particularly when discussing water potential.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: The Principles of Homeostasis and Negative Feedback

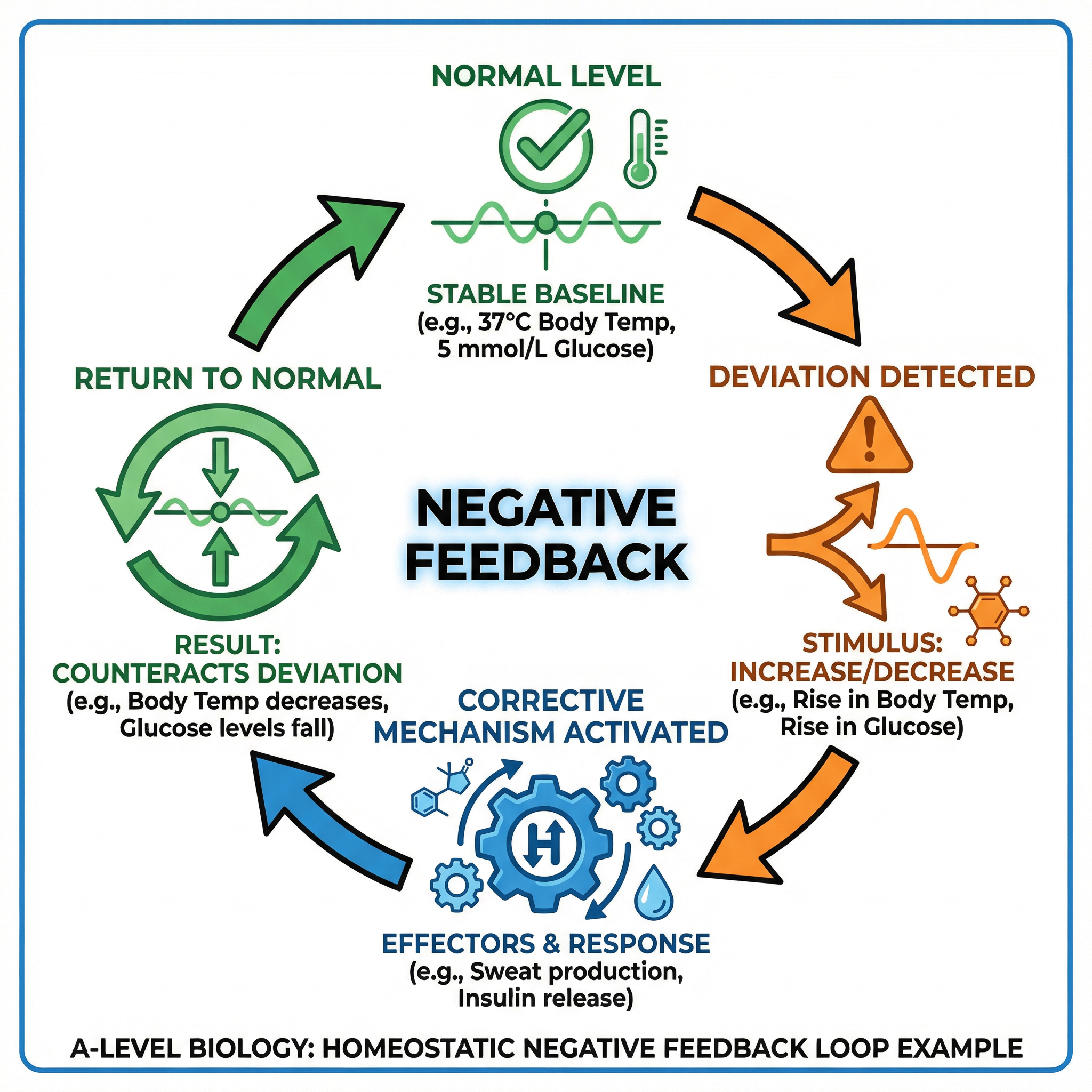

Homeostasis relies on negative feedback loops to maintain stability. These loops detect deviations from a set 'norm' and trigger corrective mechanisms to restore conditions to that original level. This process involves a sequence of events: a stimulus causes a change, which is detected by a receptor. The receptor communicates with a coordinator (often the brain or a specific gland), which in turn instructs an effector (like a muscle or gland) to carry out a response. This response counteracts the initial change, thus completing the loop.

Example: If your body temperature rises above the 37°C norm, thermoreceptors in your skin and hypothalamus detect this. The hypothalamus coordinates a response, causing effectors like sweat glands to secrete sweat and arterioles in the skin to vasodilate. This cools the body, returning its temperature to the norm.

Concept 2: Blood Glucose Regulation

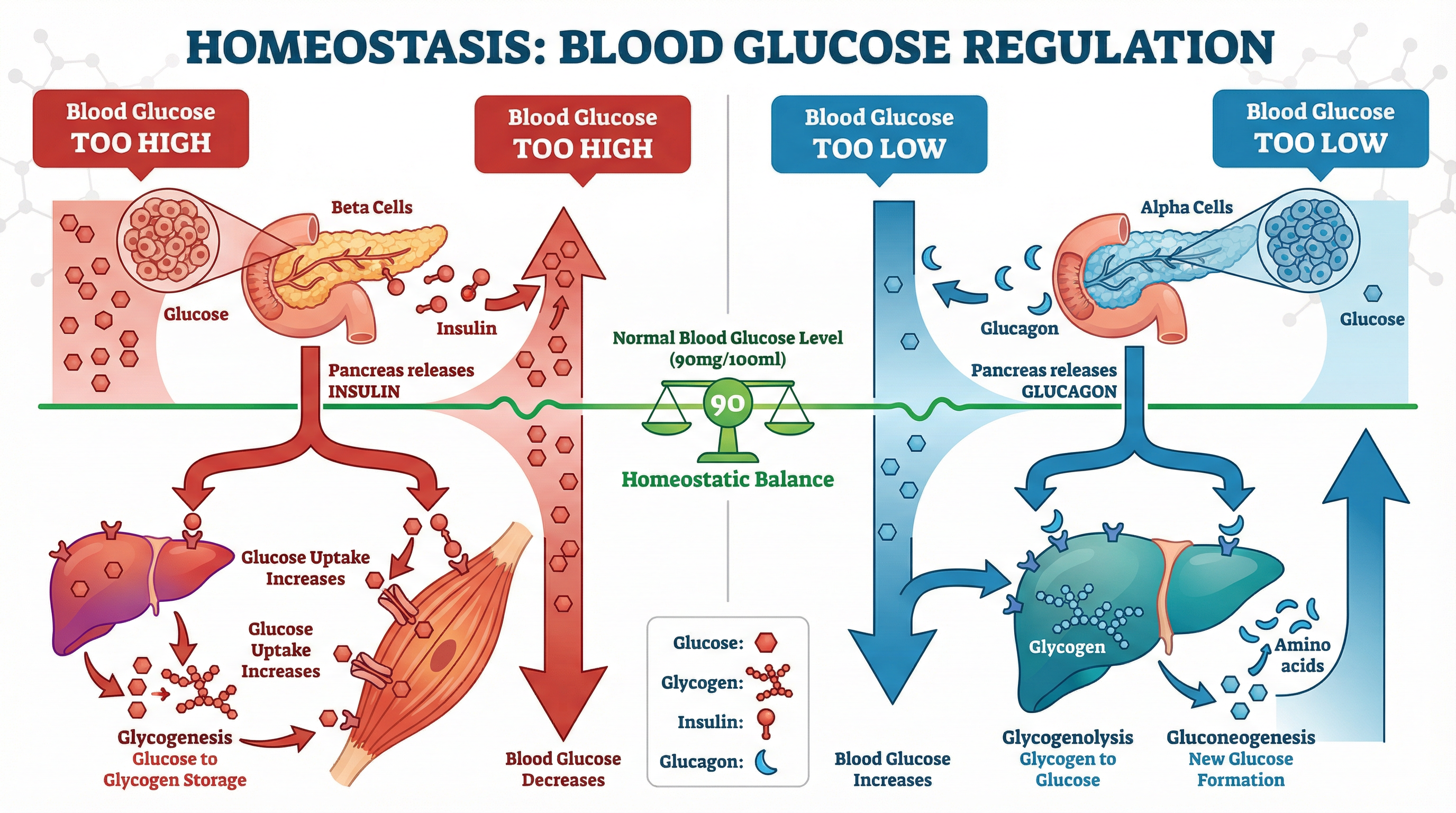

The concentration of glucose in the blood must be kept within a narrow range (around 90 mg per 100 cm³). This is controlled by the hormones insulin and glucagon, which are produced in the pancreas.

If blood glucose is too high:

- Detection: Beta cells in the Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas detect the rise.

- Response: Beta cells secrete insulin into the bloodstream.

- Action: Insulin binds to specific, complementary receptors on the cell surface membranes of liver and muscle cells. This has two main effects:

- It increases the permeability of muscle cells to glucose by causing the recruitment of GLUT4 transporter proteins to the cell membrane.

- It activates enzymes in liver and muscle cells that convert glucose into glycogen for storage (a process called glycogenesis).

- Result: More glucose is removed from the blood, and its concentration returns to the normal level.

If blood glucose is too low:

- Detection: Alpha cells in the Islets of Langerhans detect the fall.

- Response: Alpha cells secrete glucagon into the bloodstream.

- Action: Glucagon binds to specific receptors on liver cells only. This activates enzymes that:

- Break down stored glycogen into glucose (glycogenolysis).

- Synthesise glucose from non-carbohydrate sources like amino acids and glycerol (gluconeogenesis).

- Result: Glucose is released into the blood, and its concentration returns to the normal level.

The Second Messenger Model: Adrenaline and glucagon work via the second messenger model. The hormone (the first messenger) binds to a receptor on the target cell membrane, activating the enzyme adenylate cyclase. This enzyme converts ATP into cyclic AMP (cAMP), the second messenger, which then activates a cascade of enzymes within the cell to bring about the final response.

Concept 3: Osmoregulation and the Kidney

Osmoregulation is the control of the water potential of the blood. The kidney is the primary organ responsible for this, producing urine of varying concentration and volume depending on the body’s needs.

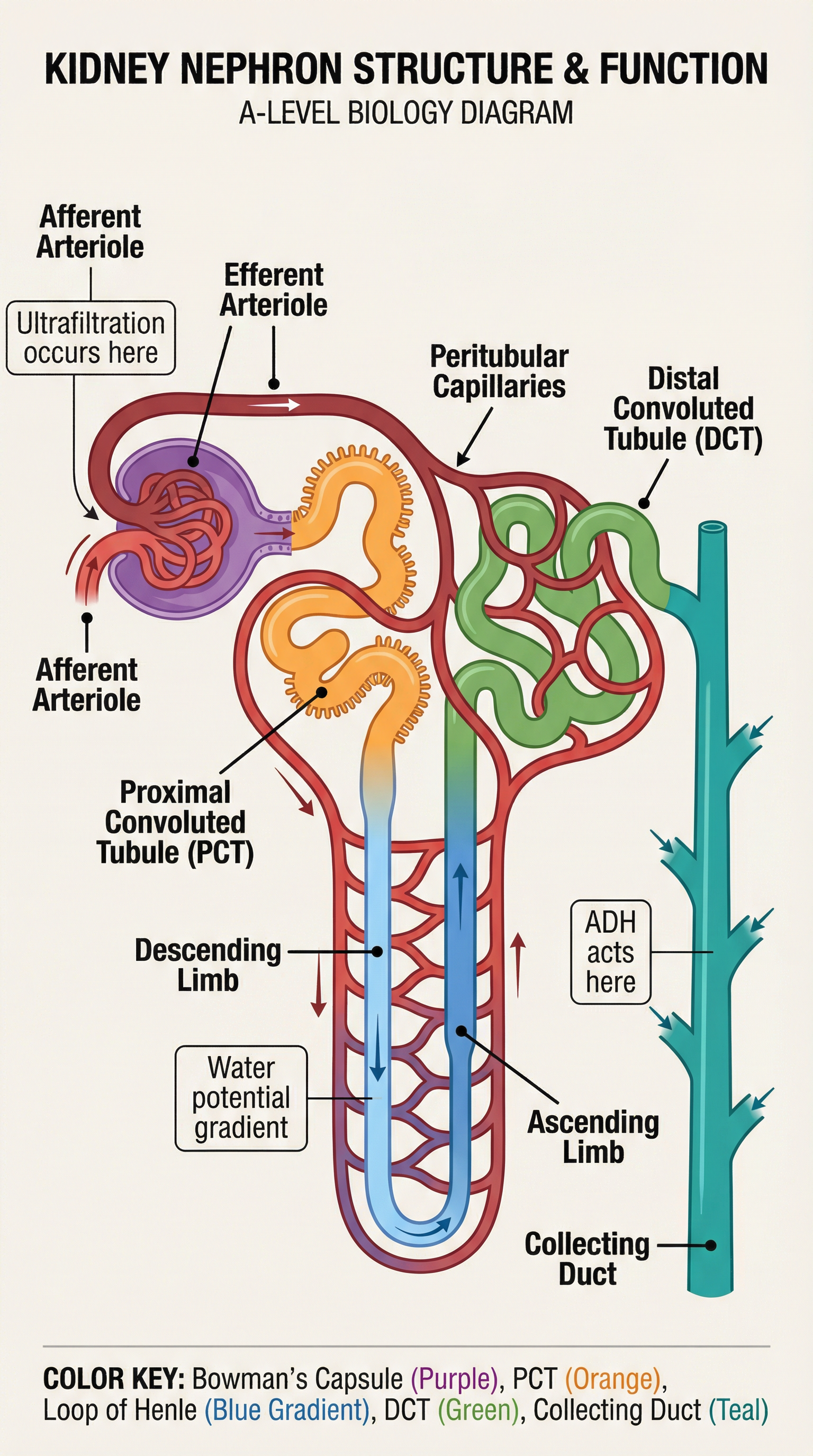

The Nephron: Each kidney contains over a million microscopic tubules called nephrons. Key processes occur in distinct parts of the nephron:

-

Ultrafiltration (Bowman's Capsule): Blood enters the glomerulus under high hydrostatic pressure from the afferent arteriole. This pressure forces water, glucose, mineral ions, and urea out of the blood and into the Bowman's capsule, forming the glomerular filtrate. Blood cells and large proteins are too large to pass through and remain in the blood.

-

Selective Reabsorption (Proximal Convoluted Tubule - PCT): All glucose and amino acids, and most ions and water, are reabsorbed from the filtrate back into the blood. This occurs via active transport and co-transport mechanisms.

-

Maintaining a Sodium Ion Gradient (Loop of Henle): The Loop of Henle acts as a counter-current multiplier. The ascending limb actively transports Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions out into the medulla, making it impermeable to water. This lowers the water potential in the interstitial fluid of the medulla. The descending limb is permeable to water but not ions, so water moves out by osmosis into the medulla and is reabsorbed into the blood.

-

Hormonal Control of Water Reabsorption (Distal Convoluted Tubule & Collecting Duct): The final adjustment of water content occurs here, under the control of the hormone ADH (Anti-diuretic Hormone).

- Dehydration: If the blood has a low water potential, osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus detect this. The posterior pituitary gland releases more ADH.

- ADH Action: ADH binds to receptors on the cells of the DCT and collecting duct, causing the insertion of aquaporin channels into their cell surface membranes.

- Result: The tubule becomes more permeable to water. More water is reabsorbed from the filtrate back into the blood by osmosis, down the water potential gradient created by the Loop of Henle. This produces a small volume of concentrated urine.

Practical Applications

Understanding homeostasis is vital in medicine. Diabetes mellitus is a condition where blood glucose control is faulty. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease where the body attacks its own beta cells, meaning no insulin is produced. It is treated with regular insulin injections. Type 2 diabetes involves either a lack of insulin or the body's cells becoming unresponsive to it (insulin resistance), often linked to lifestyle factors. It can be managed with diet, exercise, and sometimes medication.

Kidney failure, where the kidneys can no longer filter the blood effectively, is treated with dialysis or a kidney transplant. Dialysis fluid contains a normal concentration of glucose and ions, so these are not removed from the blood, but it contains no urea, so urea diffuses out of the blood down its concentration gradient.