Study Notes

Overview

The Human Endocrine System is your body's internal communication network, using chemical messengers called hormones to regulate long-term processes like growth, metabolism, and reproduction. Unlike the nervous system which sends rapid electrical signals, the endocrine system provides a slower, more sustained level of control. For your AQA GCSE exam, this topic (specification reference 4.5.3) is crucial, frequently appearing in both multiple-choice and long-answer questions. A solid understanding of how glands, hormones, and feedback mechanisms work together is essential for achieving a high grade. This guide will walk you through the core concepts, from the role of the 'master gland' to the intricate control of blood glucose, ensuring you are fully prepared to tackle any question an examiner throws at you.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Principles of Hormonal Control

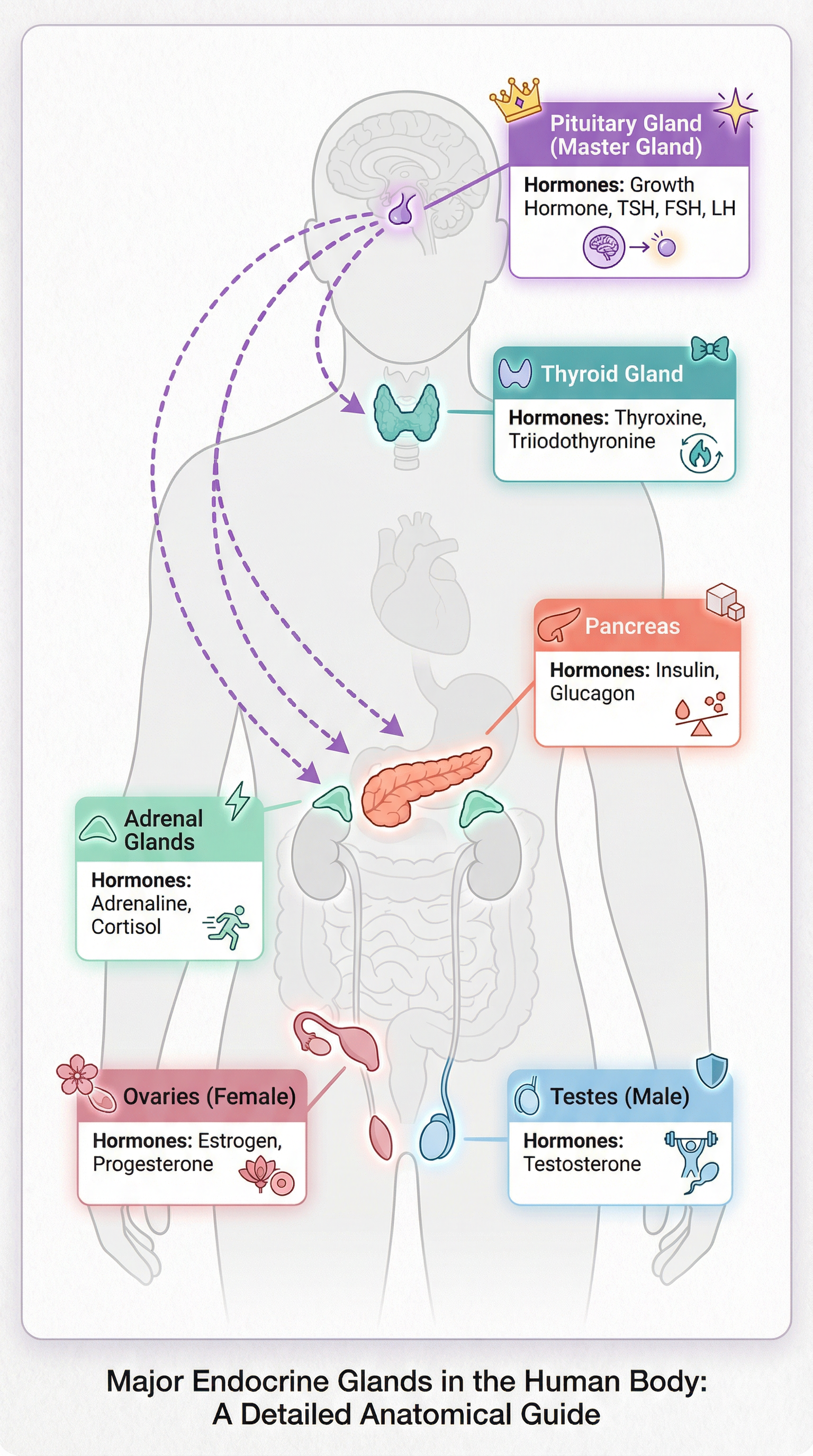

Hormones are chemical molecules released directly into the blood by endocrine glands. They travel around the body in the blood plasma but only affect specific target organs or tissues that have the correct complementary receptor proteins. Think of it like a key (the hormone) only fitting a specific lock (the receptor). This ensures that hormones only act where they are needed. The pituitary gland, located at the base of the brain, is often called the 'master gland' because it releases a number of different hormones that, in turn, act on other endocrine glands, stimulating them to release their own hormones. This creates a cascade of responses.

Concept 2: Blood Glucose Regulation and Negative Feedback

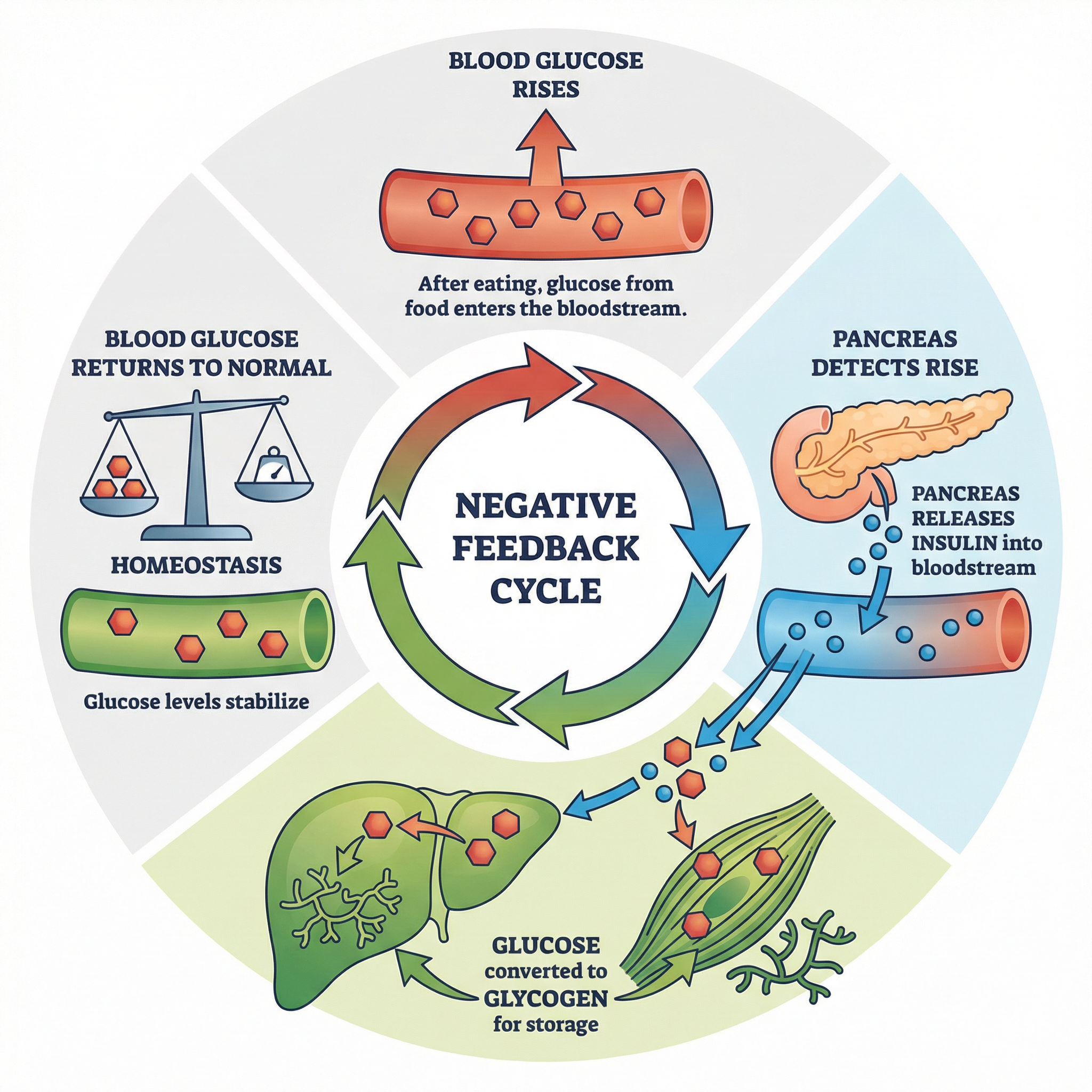

Maintaining a stable blood glucose concentration is a critical homeostatic process. This is controlled by two hormones produced in the pancreas: insulin and glucagon. This is a perfect example of a negative feedback cycle, a mechanism that brings conditions back to their normal or optimum level.

-

If blood glucose is too high (e.g., after a sugary meal), the pancreas detects this and secretes insulin.

-

Insulin travels in the blood to the liver and muscles.

-

It causes cells to take up more glucose from the blood and stimulates the liver to convert excess glucose into an insoluble carbohydrate called glycogen for storage.

-

This causes the blood glucose level to fall back to the normal range.

-

If blood glucose is too low (e.g., after strenuous exercise), the pancreas detects this and secretes glucagon.

-

Glucagon travels to the liver.

-

It stimulates the liver to break down its stored glycogen back into glucose and release it into the blood.

-

This causes the blood glucose level to rise back to the normal range.

Concept 3: Diabetes

Diabetes is a condition where the body cannot effectively control its blood glucose levels. In Type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce enough (or any) insulin. This is an autoimmune condition where the body's own immune system attacks the insulin-producing cells. It is treated with insulin injections, allowing glucose to be taken up by cells and preventing blood glucose from rising to dangerous levels. In Type 2 diabetes, the body's cells no longer respond properly to the insulin that is produced (this is called insulin resistance). It is often linked to lifestyle factors like obesity and lack of exercise, and can be managed through diet, exercise, and sometimes medication.

Concept 4: Adrenaline and Thyroxine (Higher Tier)

Adrenaline is the 'fight or flight' hormone, released from the adrenal glands (located on top of the kidneys) in times of fear or stress. It prepares the body for action by:

- Increasing the heart rate and breathing rate.

- Stimulating the liver to break down glycogen into glucose, providing more energy for the muscles.

- Diverting blood flow away from non-essential areas (like the digestive system) towards the muscles and brain.

Thyroxine, produced by the thyroid gland in the neck, regulates the body's metabolic rate. Its release is controlled by a negative feedback loop involving the pituitary gland and Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH). A low level of thyroxine in the blood stimulates the pituitary to release TSH, which causes the thyroid to release more thyroxine. A high level of thyroxine inhibits the release of TSH, reducing thyroxine production. This ensures a stable metabolic rate.