Study Notes

Overview

Plant hormones, also called phytohormones, are chemical messengers that regulate growth, development, and responses to environmental stimuli in plants. Unlike animal hormones that travel through blood, plant hormones diffuse through plant tissues from their site of production. This topic is central to understanding how plants adapt to their surroundings without a nervous system. In Edexcel GCSE Biology, you'll study how auxins control tropisms—growth responses to directional stimuli like light and gravity. Higher Tier candidates must also understand the commercial exploitation of gibberellins and ethene in modern agriculture. Exam questions typically focus on explaining the mechanism of auxin redistribution, distinguishing between effects in shoots versus roots, and evaluating the economic and environmental impacts of hormone use. Expect 5-8 marks across Foundation and Higher papers, with a strong emphasis on AO2 (application) and command words like 'explain' and 'evaluate'.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: What Are Plant Hormones?

Plant hormones are organic compounds produced in tiny quantities that regulate physiological processes throughout the plant. Unlike animals, plants lack a circulatory system, so hormones move by diffusion through cell walls and plasmodesmata. The most important hormone for GCSE is auxin, specifically indoleacetic acid (IAA), which is synthesized in meristems—regions of active cell division at shoot and root tips. Auxins influence cell elongation, not cell division, by loosening cell walls and allowing turgor pressure to stretch cells. This distinction is critical: candidates who state auxins cause mitosis will lose marks. Other key hormones include gibberellins (promote germination and stem elongation) and ethene (a gaseous hormone controlling ripening and senescence). Understanding that these hormones act at very low concentrations and can have opposite effects depending on tissue type is fundamental to mastering this topic.

Example: A shoot tip produces auxin continuously. If you remove the tip, the shoot stops bending towards light, demonstrating that the tip is the source of the hormone controlling phototropism.

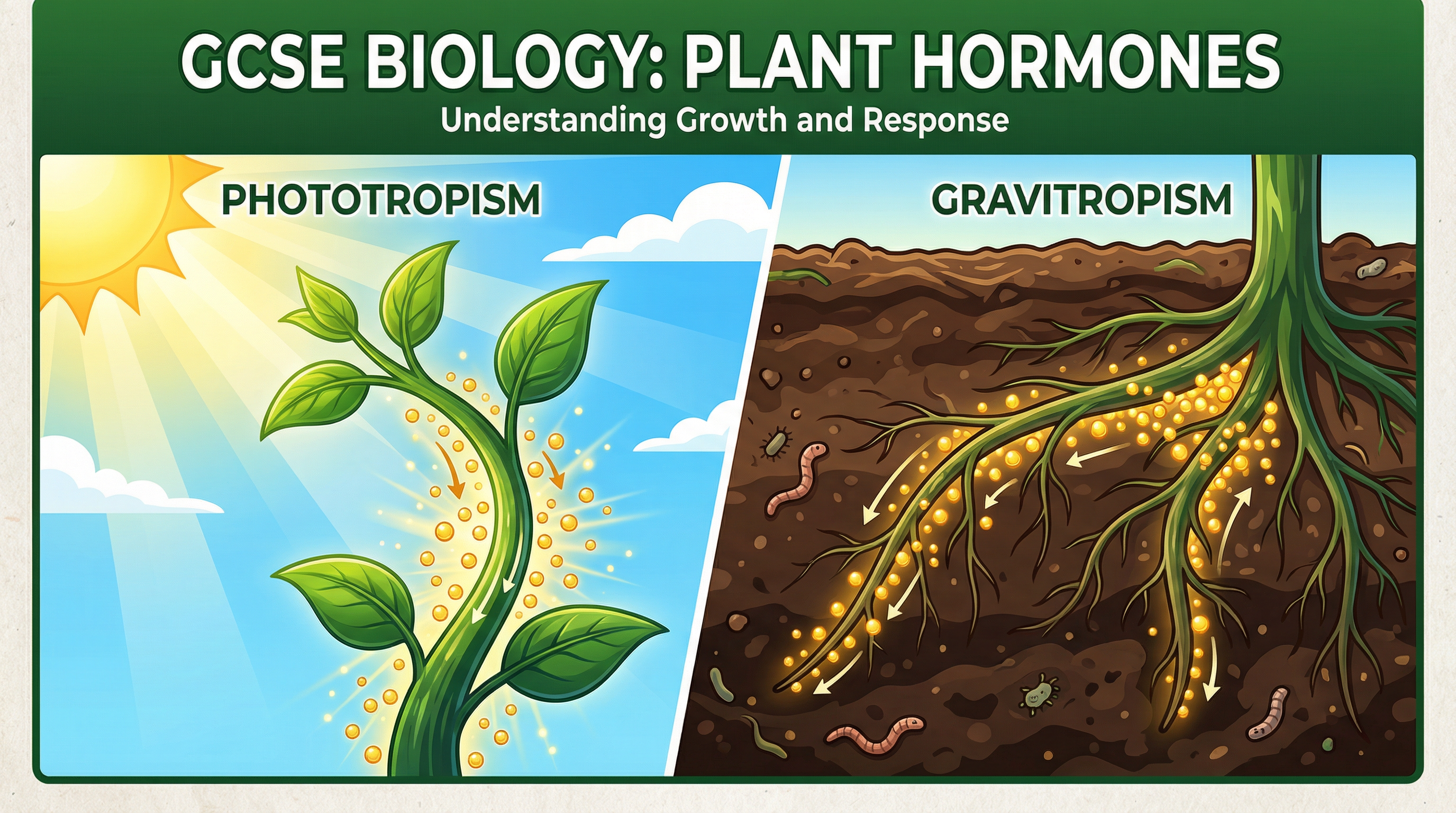

Concept 2: Tropisms—Growth Responses to Directional Stimuli

A tropism is a directional growth response where the direction of growth is determined by the direction of the stimulus. The two tropisms you must know are phototropism (response to light) and gravitropism or geotropism (response to gravity). Positive tropism means growth towards the stimulus; negative tropism means growth away from it. Shoots exhibit positive phototropism (grow towards light) and negative gravitropism (grow away from gravity, i.e., upwards). Roots exhibit positive gravitropism (grow towards gravity, i.e., downwards) and negative phototropism (grow away from light, though this is less pronounced). These responses are adaptive: shoots need light for photosynthesis, while roots need to anchor the plant and access water in the soil. The mechanism underlying tropisms is the unequal distribution of auxin, which causes differential growth rates on opposite sides of the organ.

Example: A potted plant placed on a windowsill will bend towards the window within a few days due to positive phototropism in the shoot.

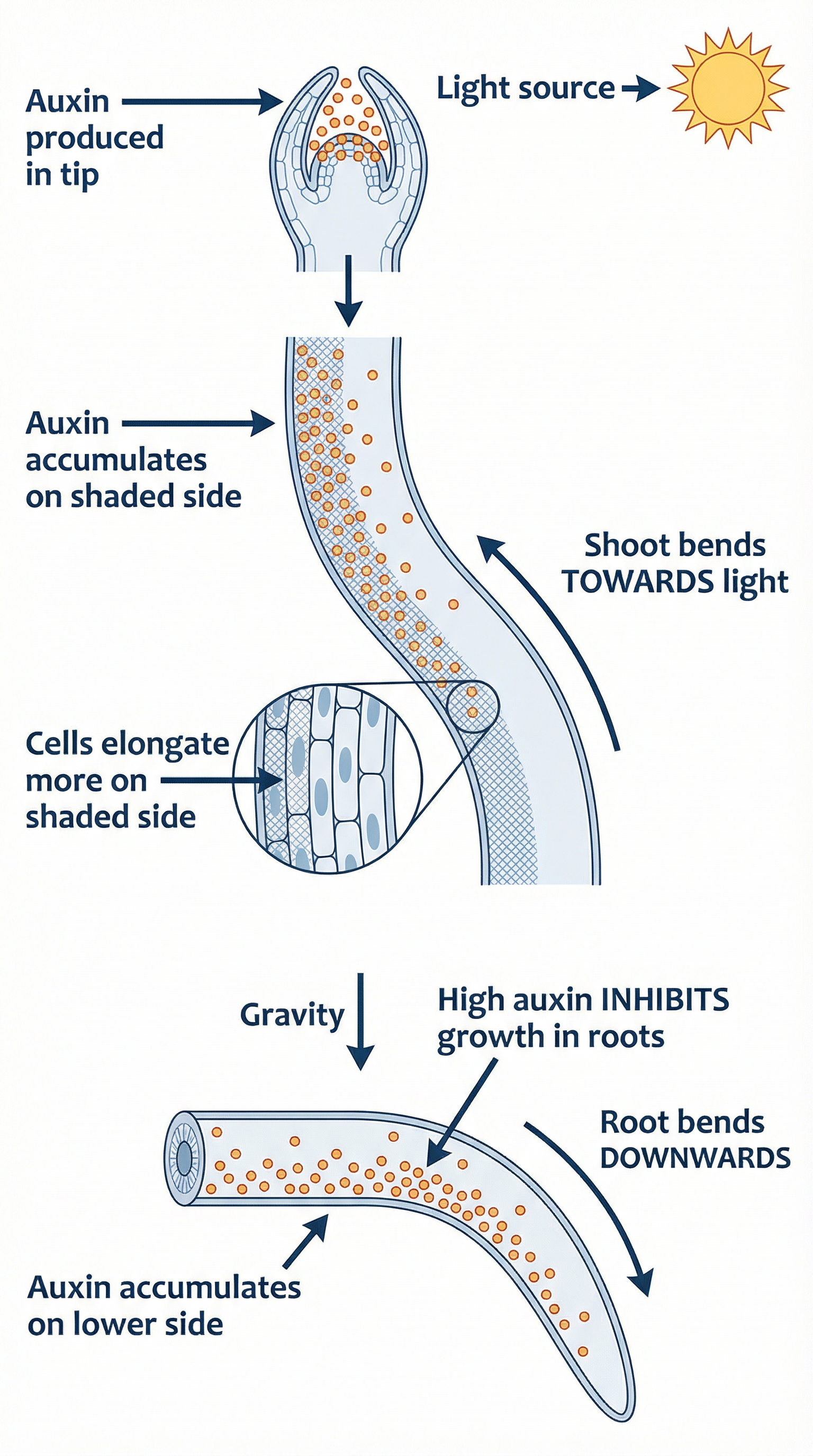

Concept 3: Phototropism in Shoots—How Auxin Causes Bending Towards Light

When light shines on a shoot from one side, auxin produced in the shoot tip redistributes. Crucially, auxin moves away from the light source and accumulates on the shaded side of the shoot. In shoot cells, auxin stimulates cell elongation by activating proton pumps that acidify the cell wall, loosening cellulose fibers and allowing cells to expand. Because the shaded side has more auxin, cells there elongate more than cells on the illuminated side. This unequal growth causes the shoot to bend towards the light—positive phototropism. Examiners award marks for stating: (1) auxin is produced in the tip, (2) auxin diffuses/moves to the shaded side, (3) auxin stimulates cell elongation, and (4) unequal elongation causes bending. Avoid saying auxin moves towards light or causes cell division—both are incorrect and will lose marks.

Example: In a classic experiment, Charles Darwin and his son Francis showed that covering the tip of a grass seedling with an opaque cap prevented phototropism, but covering the base did not, proving the tip detects light and produces the growth-regulating substance (later identified as auxin).

Concept 4: Gravitropism in Roots—Why High Auxin Inhibits Root Growth

Roots must grow downwards to anchor the plant and absorb water and minerals. When a root is placed horizontally, gravity causes auxin to accumulate on the lower side of the root. However, in roots, high concentrations of auxin inhibit cell elongation rather than stimulate it. This means the lower side grows more slowly than the upper side, causing the root to bend downwards—positive gravitropism. This opposite effect of auxin in roots versus shoots is a key concept examiners test repeatedly. The mechanism involves auxin inhibiting the elongation zone cells in roots, possibly by interfering with cell wall loosening or by promoting the synthesis of growth inhibitors. When explaining gravitropism in roots, you must state: (1) auxin accumulates on the lower side due to gravity, (2) high auxin concentration inhibits root cell elongation, and (3) the upper side grows faster, bending the root downwards.

Example: If you place a germinating bean seed on its side, the root will curve downwards within 24 hours due to positive gravitropism, even in complete darkness.

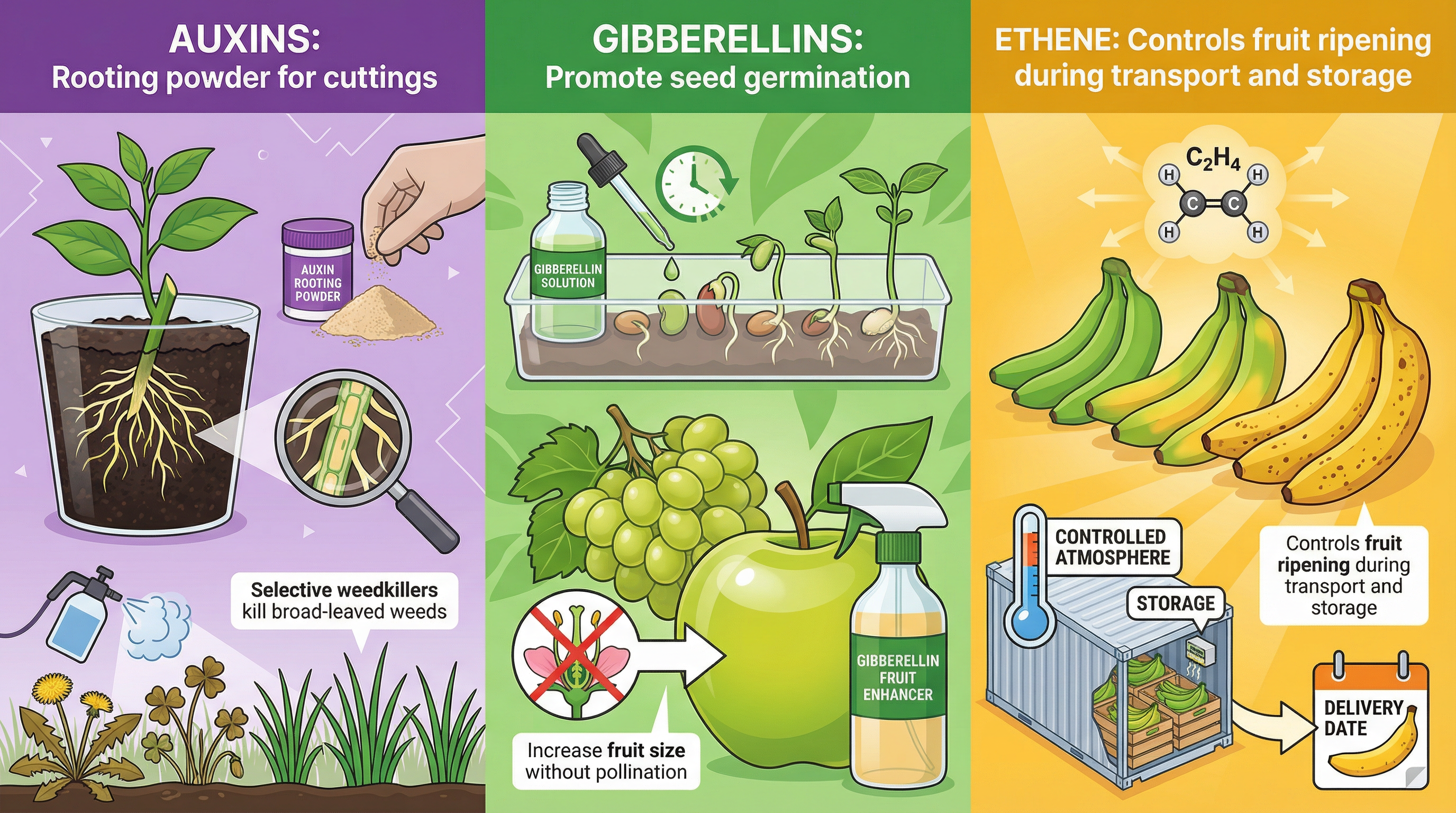

Concept 5: Commercial Uses of Auxins (Higher Tier)

Auxins have two major commercial applications. First, they are used in rooting powders (also called rooting hormones). When gardeners take cuttings from plants, they dip the cut end in powder containing synthetic auxins, which stimulates adventitious root formation, helping the cutting establish as an independent plant. This is economically valuable for propagating plants without seeds. Second, auxins are used as selective weedkillers (herbicides). Synthetic auxins like 2,4-D cause uncontrolled, rapid growth in broad-leaved dicot weeds (like dandelions), disrupting their vascular tissue and killing them, while narrow-leaved monocot crops (like wheat, barley, and grass) are unaffected because they are less sensitive to these auxins. This selectivity allows farmers to control weeds without harming crops, increasing yields. However, environmental concerns include potential harm to non-target wildflowers and biodiversity if herbicides drift beyond fields.

Example: A farmer sprays a wheat field with 2,4-D herbicide. Dandelions and thistles die due to uncontrolled growth, but the wheat plants continue growing normally, resulting in higher crop yields.

Concept 6: Commercial Uses of Gibberellins (Higher Tier)

Gibberellins are plant hormones that promote stem elongation, seed germination, and fruit development. Commercially, gibberellins are used to end seed dormancy and promote germination, even under suboptimal conditions like low temperatures. This allows growers to produce crops out of season or in challenging climates. Gibberellins are also sprayed on fruit crops to increase fruit size without pollination, producing seedless fruits like seedless grapes. This is economically beneficial because larger fruits command higher prices, and seedless varieties are popular with consumers. Gibberellins work by stimulating cell division and elongation in the fruit, and by activating enzymes that mobilize food reserves in seeds. In exam questions, you might be asked to evaluate the benefits (higher yields, seedless fruit, faster germination) against costs (expense of hormone application, potential environmental impacts).

Example: Grape growers spray gibberellin on grape clusters to produce larger, seedless grapes that are more attractive to consumers and fetch higher market prices.

Concept 7: Commercial Uses of Ethene (Higher Tier)

Ethene (ethylene) is a gaseous plant hormone that regulates fruit ripening, leaf abscission, and senescence. Commercially, ethene is used to control the timing of fruit ripening. Fruits like bananas, tomatoes, and avocados are often harvested when unripe (green) to prevent damage during long-distance transport. They are stored in controlled atmospheres with low ethene levels to delay ripening. When the fruit reaches its destination, ethene gas is released into storage rooms to trigger uniform, rapid ripening, ensuring the fruit is ready for sale. This allows global distribution of fresh produce and reduces waste from over-ripening during transport. Ethene works by activating genes that produce enzymes breaking down cell walls, converting starches to sugars, and changing pigments. In 'evaluate' questions, consider benefits (reduced waste, global trade, consumer access to fresh fruit) versus drawbacks (energy costs of controlled storage, potential loss of flavor compared to naturally ripened fruit).

Example: Bananas are picked green in tropical countries, shipped in refrigerated containers with low ethene, and then exposed to ethene gas in ripening rooms at supermarkets, turning yellow and sweet just before sale.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

There are no formulas to memorize for this topic, but you should understand the inverse relationship between auxin concentration and growth rate in roots versus shoots:

- In shoots: Growth rate increases with auxin concentration (up to an optimal level, beyond which it may inhibit growth).

- In roots: Growth rate decreases with increasing auxin concentration; high auxin inhibits root elongation.

This relationship is sometimes shown graphically in exam questions. You may be asked to interpret a graph showing auxin concentration on the x-axis and growth rate on the y-axis, with separate curves for shoots and roots. The shoot curve rises, while the root curve falls, illustrating the opposite effects.

Practical Applications

While there is no specific required practical for plant hormones in Edexcel GCSE, you may encounter questions based on investigative scenarios. For example:

Investigation: Does the shoot tip control phototropism?

- Apparatus: Seedlings (e.g., cress or oat), light source, opaque caps, ruler, protractor.

- Method: Grow seedlings in uniform light. Divide into groups: (1) control (no treatment), (2) tip covered with opaque cap, (3) base covered with opaque cap. Place all seedlings with light from one side. Measure the angle of bending after 24-48 hours.

- Expected Results: Control seedlings and those with base covered bend towards light. Seedlings with tip covered do not bend, showing the tip is essential for detecting light and producing auxin.

- Common Errors: Not controlling variables (temperature, water, seedling age), not measuring angles accurately, confusing which part was covered.

- Exam Testing: You might be asked to identify the independent variable (which part is covered), dependent variable (angle of bending), or suggest improvements (use more seedlings for reliability, repeat the experiment).

Another common practical question involves investigating gravitropism by placing seedlings horizontally and observing root and shoot curvature over time.

Podcast: Plant Hormones Explained

Listen to this 10-minute podcast for a comprehensive audio revision of the topic, including exam tips, common mistakes, and a quick-fire recall quiz.