Study Notes

Overview

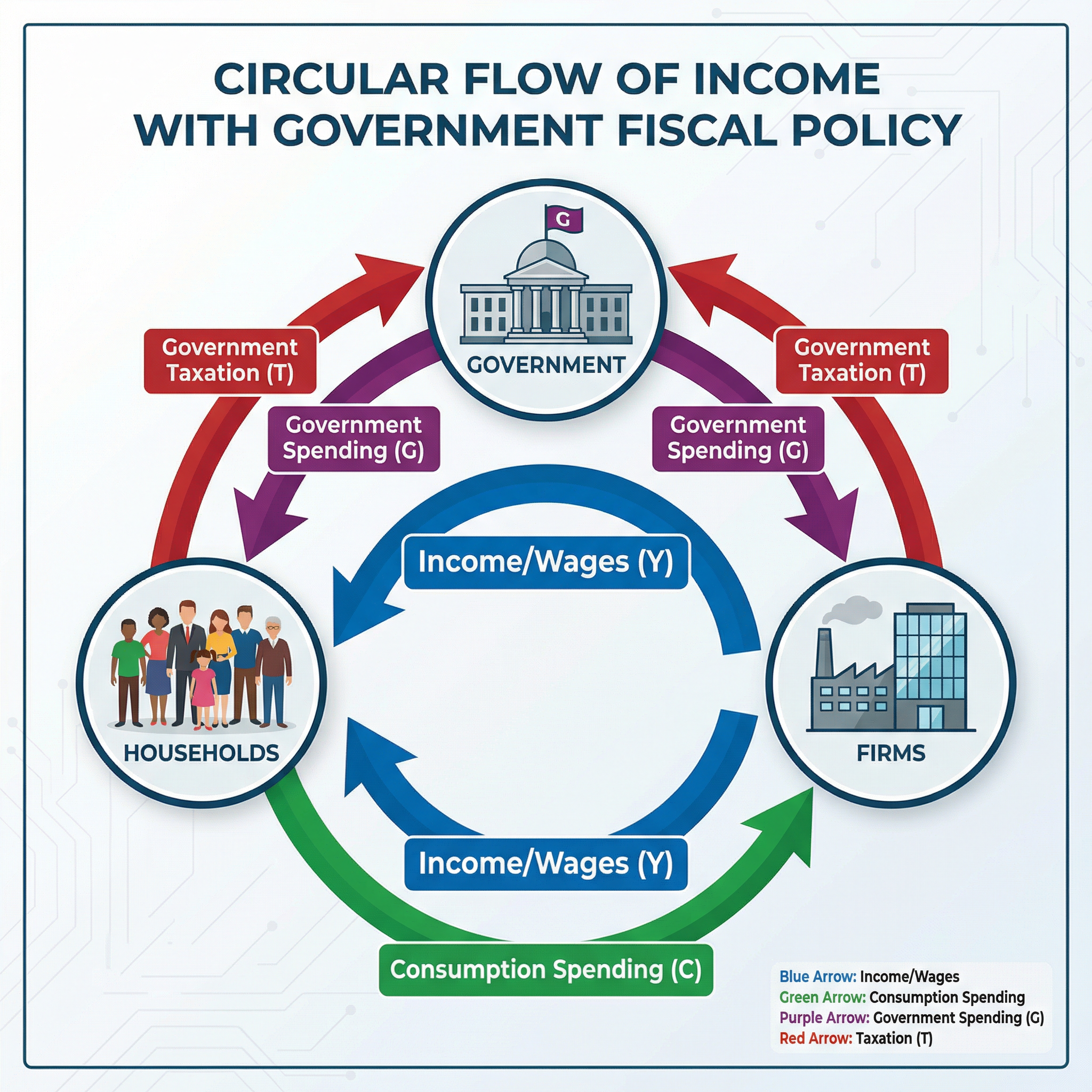

Fiscal policy is a fundamental tool of macroeconomic management, concerning the use of government spending and taxation to influence the economy. For the OCR J205 specification, candidates must demonstrate a precise understanding of how these instruments are used to pursue the government's main objectives: sustainable economic growth, low unemployment, price stability, and a fair distribution of income. This guide will break down the core mechanisms of fiscal policy, from the distinction between direct and indirect taxes to the critical difference between a budget deficit and the national debt. Examiners expect candidates to build logical chains of reasoning, analyse trade-offs, and apply their knowledge to specific case study contexts. A firm grasp of this topic is essential for achieving high marks, as it forms the bedrock of demand-side policy analysis.

Key Concepts: The Instruments of Fiscal Policy

Government Spending (G)

What it is: This refers to all money spent by the state. It can be broken down into three main types: Current Spending (day-to-day running of public services like wages for nurses and teachers), Capital Spending (long-term investment in infrastructure like new hospitals, schools, and transport links), and Transfer Payments (welfare payments like pensions and unemployment benefits, which redistribute income but don't directly add to national output).

Why it matters: Government spending is a direct component of Aggregate Demand (AD = C + I + G + X - M). An increase in G will, ceteris paribus, shift the AD curve to the right, leading to higher economic growth and lower unemployment in the short term. Furthermore, capital spending on infrastructure, education, and healthcare can have significant supply-side benefits, boosting the economy's productive potential and shifting the Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) curve to the right. This is a crucial synoptic link that examiners credit highly.

Taxation (T)

What it is: A compulsory levy imposed by the government on individuals and firms to raise revenue and influence behaviour. There are two main categories candidates must be able to differentiate.

Specific Knowledge:

- Direct Taxes: Levied on income, wealth, or profit. They are paid directly by the person or company on whom they are levied. Examples include Income Tax, National Insurance Contributions, Corporation Tax, and Inheritance Tax. These are typically progressive, meaning they take a larger percentage of income from higher earners.

- Indirect Taxes: Levied on spending. The supplier can pass on the cost to the consumer. Examples include Value Added Tax (VAT) and Excise Duties (on fuel, alcohol, tobacco). These are typically regressive, as they take a larger proportion of income from lower earners.

Why it matters: Taxation is the primary tool for managing consumption (C) and investment (I). A cut in Income Tax increases disposable income, encouraging households to spend more, boosting AD. A cut in Corporation Tax increases firms' post-tax profits, which can be used to fund investment, also boosting AD. Conversely, tax increases can be used to dampen AD to control inflation.

The Budget Position: Deficit vs. Debt

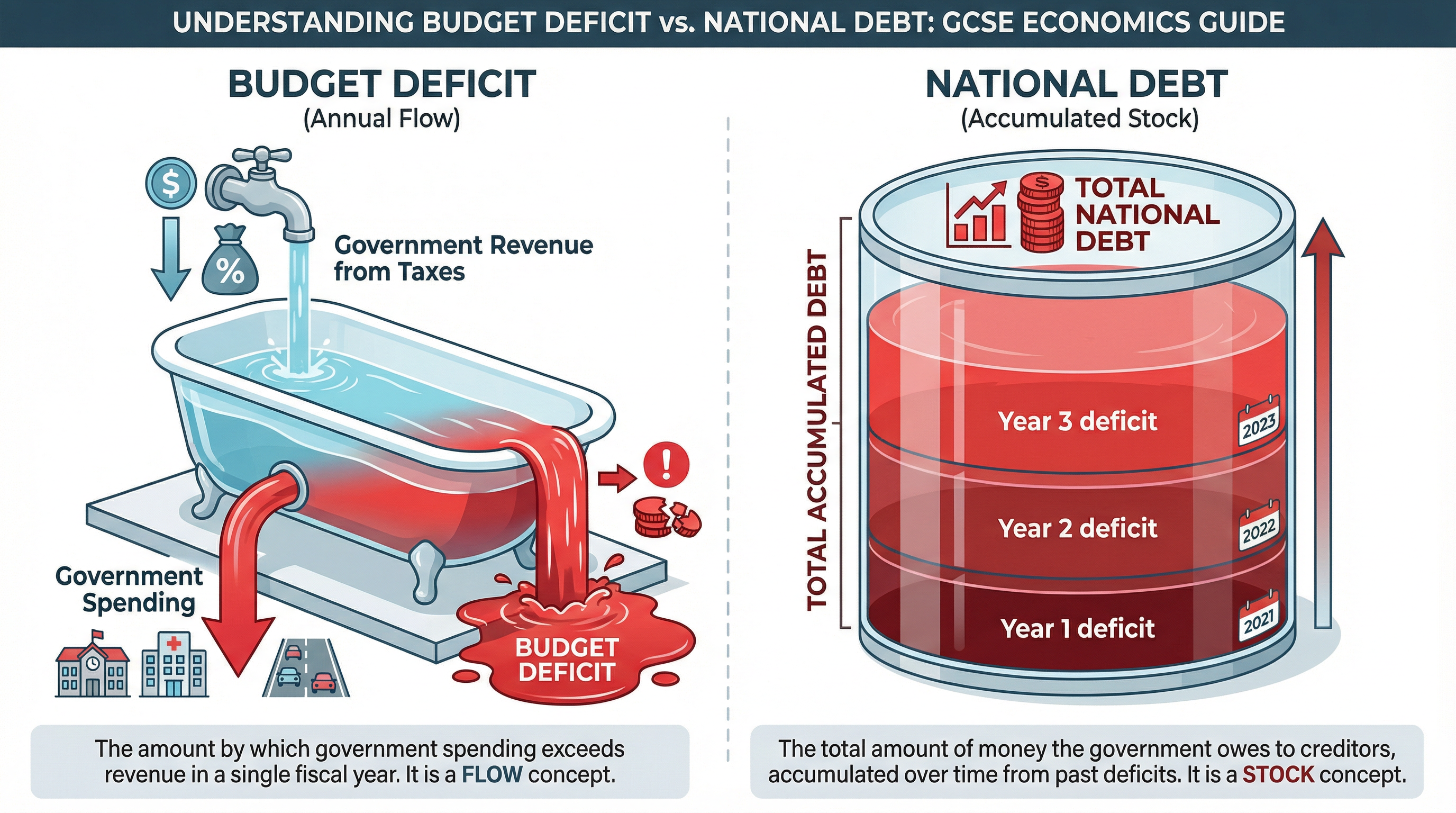

This is one of the most commonly misunderstood areas. Precision is vital.

Budget Deficit

What it is: A flow concept measured over one year. A deficit occurs when government spending is greater than tax revenue (G > T) in a single fiscal year.

Why it matters: To fund a deficit, the government must borrow money, usually by selling bonds. Persistent deficits lead to an increase in the national debt. An expansionary fiscal policy (cutting taxes or increasing spending) will likely increase the deficit.

National Debt

What it is: A stock concept. It is the total accumulated sum of all past government borrowing that has not yet been paid back.

Why it matters: A large national debt can be a problem because the government must pay interest on it. This incurs an opportunity cost – money spent on debt interest cannot be spent on public services. It can also lead to higher taxes in the future to pay the debt down.

Second-Order Concepts

Causation

Changes in fiscal policy are caused by the state of the economy relative to the government's objectives. A recession (negative economic growth, high unemployment) will trigger expansionary fiscal policy. Conversely, a period of rapid, unsustainable growth with high inflation will trigger contractionary fiscal policy (higher taxes, lower spending).

Consequence

The immediate consequence of expansionary fiscal policy is a rightward shift in AD. This leads to higher real GDP and a lower unemployment rate, but also risks causing demand-pull inflation. The long-term consequences of capital spending can include an increase in the nation's productive capacity.

Change & Continuity

Governments continuously adjust fiscal policy in the annual budget. However, the core objectives of economic management remain the same. The UK has seen a shift from heavy intervention in the post-war era to a more market-oriented approach, but the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic saw a major return to large-scale fiscal stimulus.

Significance

Fiscal policy is significant because it is the government's most direct lever for influencing the lives of its citizens. It determines the quality of public services, the level of welfare support, and the tax burden on individuals and businesses, directly impacting living standards and economic performance.