Study Notes

Overview

Family diversity is a cornerstone of contemporary British sociology and a high-value topic in the AQA GCSE specification. Candidates are expected to demonstrate knowledge of different family types, analyse the structural and cultural factors driving diversification, and evaluate contrasting theoretical perspectives. Examiners reward precise use of sociological terminology, explicit reference to legislation and statistical trends, and the ability to synthesise evidence from multiple sources. This topic frequently appears in both short-answer questions (4 marks) and extended essays (12 marks), making it essential to master both factual recall and analytical application. Understanding family diversity also provides synoptic links to topics such as social stratification, gender roles, and the relationship between the family and the state.

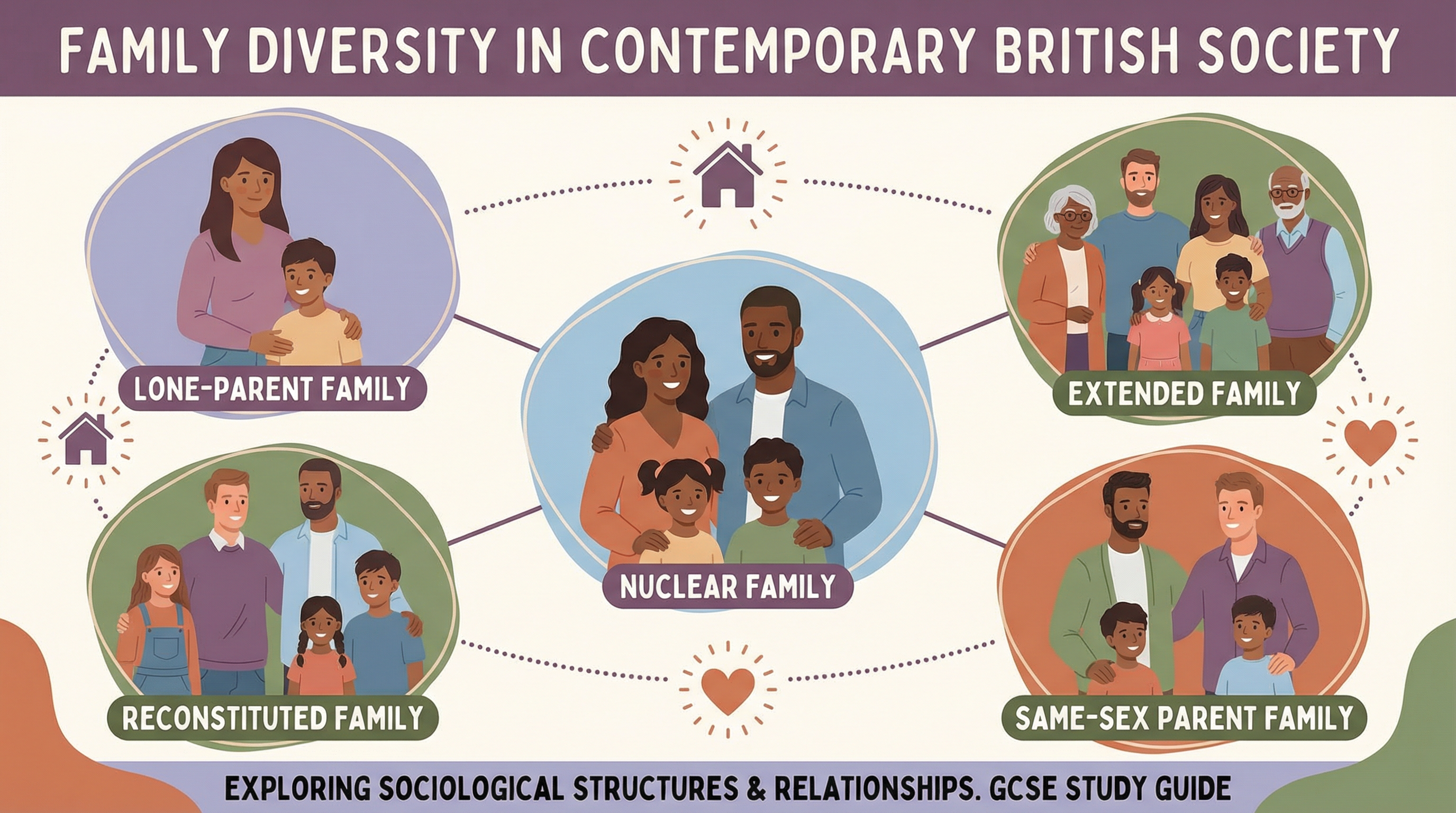

Key Family Types

Nuclear Family

Definition: A household consisting of two heterosexual parents and their dependent children, living independently from extended kin.

Historical Context: Dominant in post-war Britain (1950s-1960s), often referred to as the 'cereal packet family' due to its idealised portrayal in media and advertising.

Why It Matters: Functionalists (Parsons, Murdock) argue this is the 'ideal' family form, performing essential functions such as primary socialisation and stabilisation of adult personalities. The New Right also champions the nuclear family as the foundation of social order.

Specific Knowledge: In 1961, approximately 38% of households in the UK were nuclear families. By 2021, this had fallen to around 28%, reflecting the rise of alternative forms.

Lone-Parent Family

Definition: A household headed by a single parent (usually a mother) with dependent children, resulting from divorce, separation, death, or choice.

Why It Matters: This is the fastest-growing family type in the UK. Lone-parent families are often stigmatised by the New Right, who link them to welfare dependency and underachievement. Feminists, however, argue they represent women's independence from patriarchal marriages.

Specific Knowledge: In 2021, approximately 15% of UK families were lone-parent households, with around 90% headed by women. The Divorce Reform Act 1969 and subsequent legal changes contributed to this rise.

Extended Family

Definition: A family unit that includes relatives beyond the nuclear family, such as grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, either living together or maintaining close geographical and emotional ties.

Why It Matters: Extended families are more common in certain ethnic and cultural groups (e.g., South Asian and African-Caribbean communities). They provide mutual support, childcare, and economic assistance, challenging the notion that the nuclear family is universal.

Specific Knowledge: The 'beanpole family' is a modern variant of the extended family, characterised by multiple generations but fewer members in each generation due to lower birth rates and increased life expectancy.

Reconstituted (Blended) Family

Definition: A family formed when one or both partners bring children from previous relationships into a new partnership, creating step-parent and step-sibling relationships.

Why It Matters: Reconstituted families are a direct consequence of rising divorce and remarriage rates. They challenge traditional notions of kinship and demonstrate the fluidity of contemporary family structures.

Specific Knowledge: Approximately 10% of UK families with dependent children are reconstituted. The term 'serial monogamy' describes the pattern of individuals having multiple marriages or partnerships over their lifetime.

Same-Sex Parent Family

Definition: A household headed by two parents of the same gender, either through adoption, surrogacy, or previous heterosexual relationships.

Why It Matters: Legal recognition of same-sex relationships (Civil Partnership Act 2004, Marriage (Same-Sex Couples) Act 2013) has legitimised this family form. Postmodernists celebrate this as evidence of increasing choice and diversity.

Specific Knowledge: In 2021, there were approximately 212,000 same-sex couple families in the UK, a significant increase from previous decades.

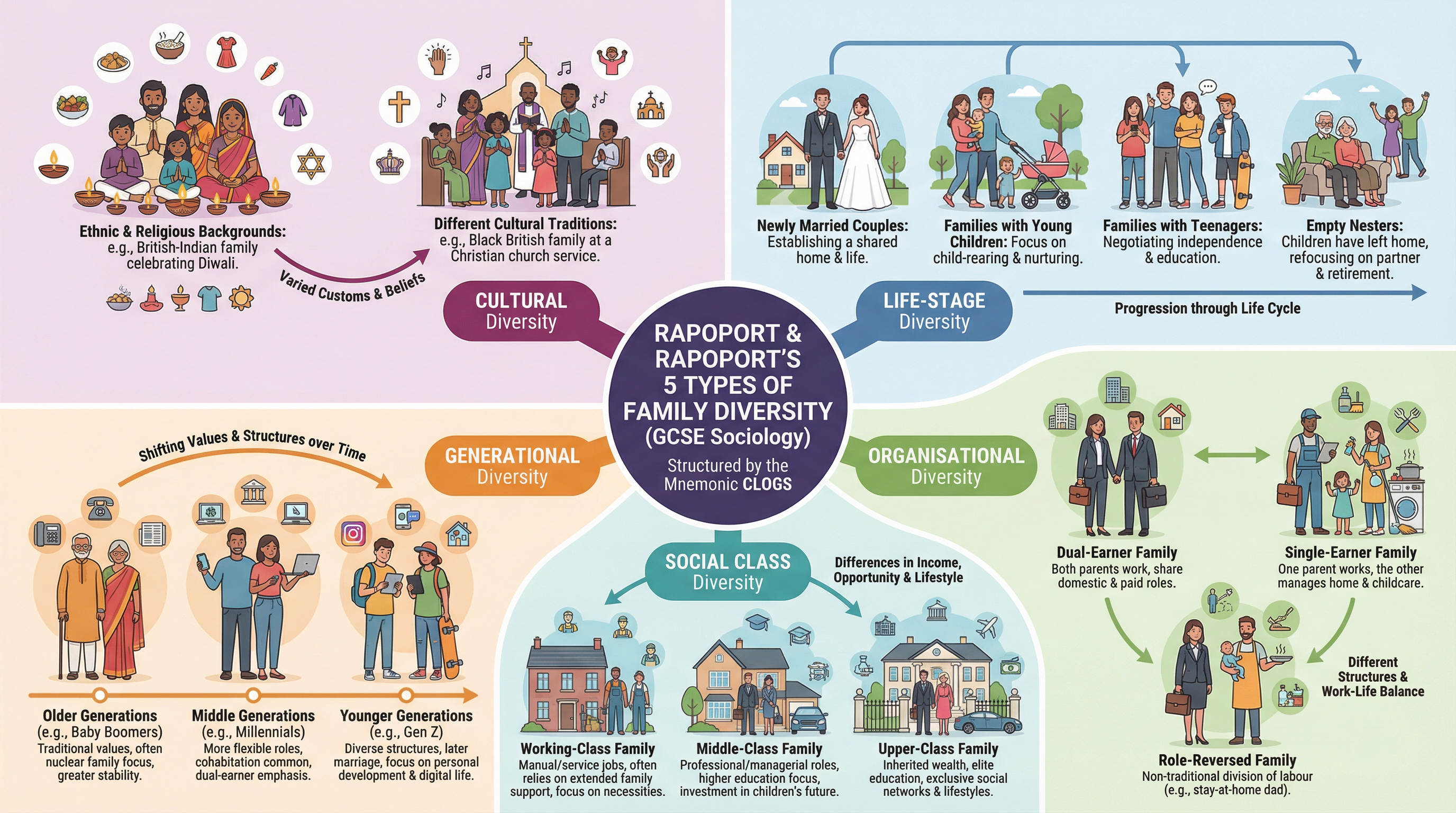

Rapoport and Rapoport's Five Types of Diversity (CLOGS)

Rhona and Robert Rapoport (1982) identified five key dimensions of family diversity, which candidates must be able to define and apply. Use the mnemonic CLOGS to remember them.

Cultural Diversity

Different ethnic, religious, and cultural groups have distinct family structures and practices. For example, British South Asian families are more likely to live in extended family units, reflecting cultural values of intergenerational support and collectivism. African-Caribbean families are more likely to be matrifocal (female-headed), partly due to historical patterns of migration and employment.

Life-Stage Diversity

Family structures change as individuals progress through the life course. A person may experience a nuclear family as a child, cohabitation as a young adult, a lone-parent family after divorce, and an 'empty nest' nuclear family in later life. This highlights the fluidity of family forms.

Organisational Diversity

Families differ in how they organise domestic labour, paid work, and childcare. Examples include dual-earner families (both partners work), single-earner families (one breadwinner), and role-reversed families (where the woman is the primary earner and the man takes on domestic responsibilities).

Generational Diversity

Different generations hold contrasting attitudes towards family life. Older generations (e.g., Baby Boomers) are more likely to value marriage and traditional gender roles, while younger generations (e.g., Millennials and Gen Z) are more accepting of cohabitation, divorce, and diverse family forms.

Social Class Diversity

Family structures and practices vary by social class. Middle-class families are more likely to invest heavily in children's education and cultural capital, while working-class families may rely more on extended kin networks for economic and emotional support. The New Right argues that an 'underclass' of welfare-dependent lone-parent families has emerged, though this view is contested.

Causes of Family Diversity

Examiners award significant credit for linking family diversity to specific structural changes. Candidates must be able to explain how and why these factors have driven diversification.

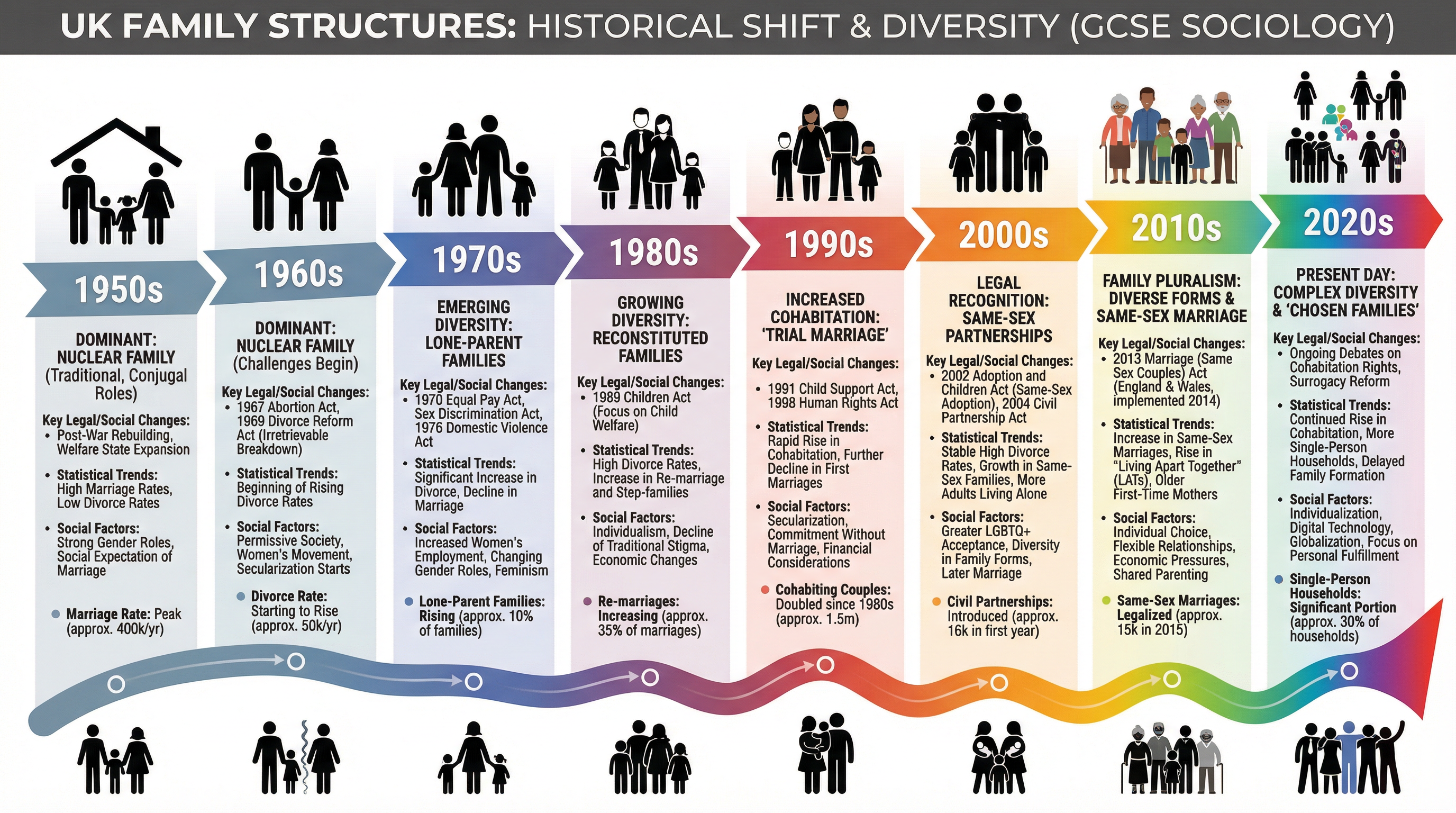

Legal Changes

The Divorce Reform Act 1969 made divorce easier and cheaper by introducing 'irretrievable breakdown' as the sole grounds for divorce, rather than requiring proof of fault. This led to a dramatic rise in divorce rates, peaking at approximately 165,000 divorces per year in 1993. Subsequent legislation, such as the Matrimonial and Family Proceedings Act 1984, reduced the waiting period for divorce from three years to one year, further facilitating family breakdown and reconstitution.

The Civil Partnership Act 2004 and Marriage (Same-Sex Couples) Act 2013 legally recognised same-sex relationships, enabling same-sex couples to form families with the same legal rights as heterosexual couples.

The Children Act 1989 emphasised the welfare of the child as paramount, regardless of family structure, reducing the stigma attached to non-nuclear families.

Secularisation

Secularisation refers to the declining influence of religion in society. As church attendance and religious belief have declined, traditional religious teachings about marriage, divorce, and family life have weakened. This has made divorce, cohabitation, and same-sex relationships more socially acceptable. In 1960, approximately 70% of the UK population identified as Christian; by 2021, this had fallen to around 46%, with a corresponding rise in those identifying as having no religion.

Changing Gender Roles

The rise of feminism and women's increased participation in education and employment have transformed family life. The Equal Pay Act 1970 and Sex Discrimination Act 1975 gave women greater economic independence, reducing their reliance on marriage for financial security. Women are now more likely to delay marriage, pursue careers, and leave unsatisfactory relationships. Feminist sociologists argue this has challenged patriarchal family structures and increased family diversity.

Economic Factors

The shift from a manufacturing to a service-based economy has created more part-time and flexible employment opportunities for women, enabling dual-earner families. However, economic insecurity and precarious employment have also made it harder for young people to form stable families, contributing to delayed marriage and increased cohabitation.

Individualisation

Postmodernist sociologists (e.g., Beck, Giddens) argue that contemporary society is characterised by individualisation, where people prioritise personal fulfilment and choice over traditional norms. This has led to the emergence of 'negotiated families', where family structures are chosen and adapted to suit individual needs, rather than being dictated by social convention.

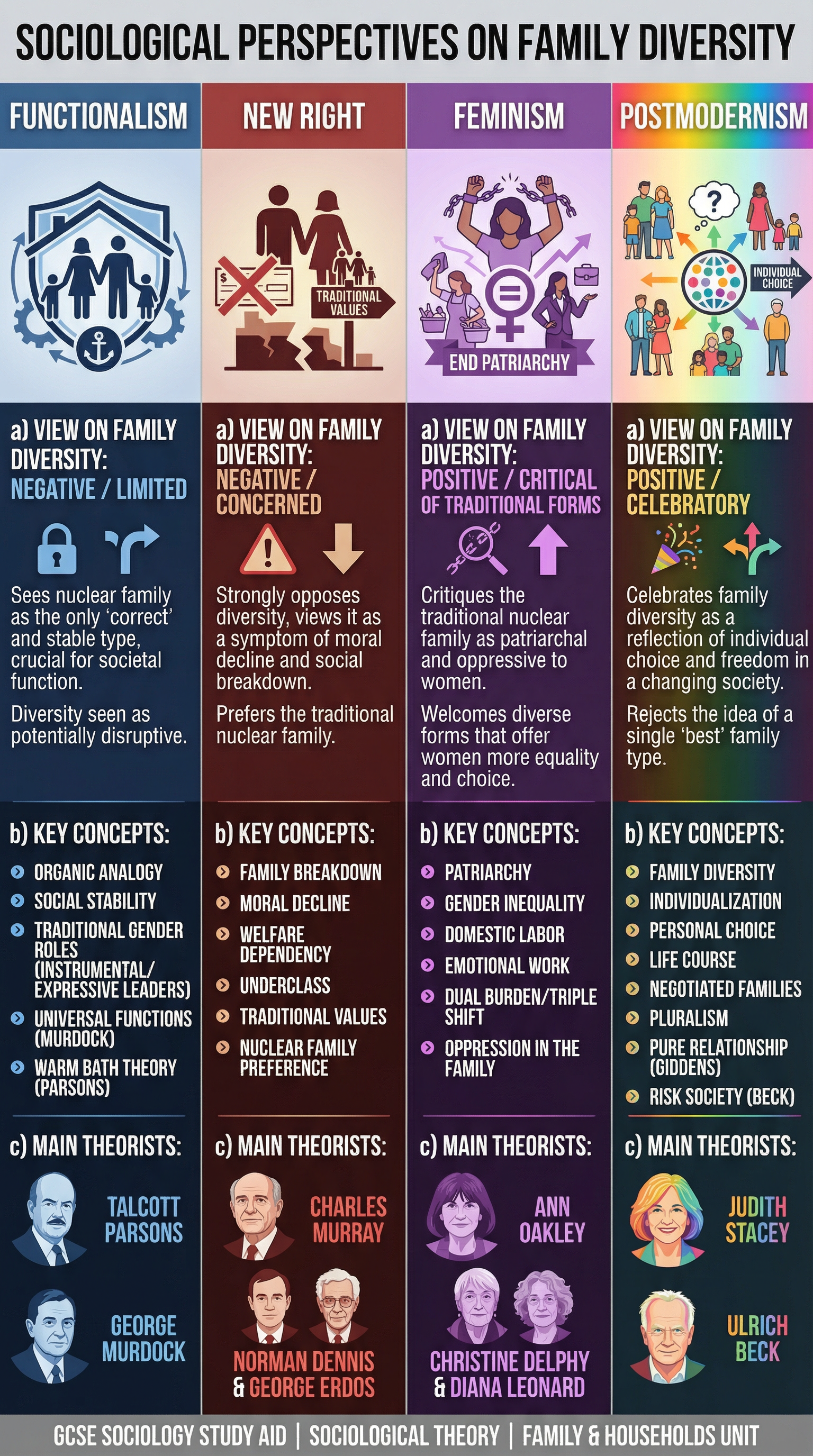

Theoretical Perspectives on Family Diversity

Candidates must be able to contrast the views of different sociological perspectives on family diversity, demonstrating AO3 (evaluation and analysis).

Functionalism: Diversity as Dysfunction

Key Theorists: Talcott Parsons, George Murdock

View on Diversity: Functionalists argue that the nuclear family is the 'ideal' family form because it performs essential functions for society, including primary socialisation of children and stabilisation of adult personalities. Parsons' 'warm bath theory' suggests the nuclear family provides emotional support and stress relief for adults. Diversity is seen as potentially disruptive to social stability.

Key Concepts: Organic analogy, social stability, traditional gender roles (instrumental and expressive leaders), universal functions (Murdock identified four: sexual, reproductive, economic, educational).

Evaluation: Critics argue Functionalism is outdated and ignores the 'dark side' of the nuclear family, such as domestic violence and inequality. It also assumes a consensus that no longer exists in diverse, multicultural societies.

New Right: Diversity as Moral Decline

Key Theorists: Charles Murray, Norman Dennis and George Erdos

View on Diversity: The New Right is a political perspective that strongly opposes family diversity, viewing it as a symptom of moral decline and social breakdown. They argue that lone-parent families, particularly those dependent on welfare, create an 'underclass' characterised by crime, educational underachievement, and welfare dependency. They advocate for policies that promote marriage and the nuclear family.

Key Concepts: Family breakdown, moral decline, welfare dependency, underclass, traditional values, nuclear family preference.

Evaluation: Critics argue the New Right stigmatises lone parents (particularly women) and ignores the positive aspects of family diversity, such as increased choice and freedom. Feminists accuse the New Right of attempting to reinforce patriarchal family structures.

Important Distinction: The New Right is a political perspective focused on policy and state intervention, whereas Functionalism is a sociological theory about social consensus. While both favour the nuclear family, their reasoning and focus differ.

Feminism: Diversity as Liberation

Key Theorists: Ann Oakley, Christine Delphy and Diana Leonard

View on Diversity: Feminists critique the traditional nuclear family as a patriarchal institution that oppresses women through the unequal division of domestic labour, emotional work, and the 'dual burden' or 'triple shift' (paid work, housework, and emotional labour). They welcome family diversity as evidence of women's increasing independence and choice. Lone-parent families, in particular, are seen as a rejection of oppressive marriages.

Key Concepts: Patriarchy, gender inequality, domestic labour, emotional work, dual burden/triple shift, oppression in the family.

Evaluation: Critics argue that not all women experience the family as oppressive, and some women actively choose traditional roles. Postmodern feminists also argue that feminism should celebrate diversity rather than assuming all women share the same experiences.

Postmodernism: Diversity as Choice and Freedom

Key Theorists: Judith Stacey, Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens

View on Diversity: Postmodernists celebrate family diversity as a reflection of individual choice and freedom in a changing society. They argue there is no longer a single 'best' family type; instead, people create 'negotiated families' and 'pure relationships' based on personal fulfilment and mutual satisfaction. Beck's concept of 'risk society' suggests that traditional structures (like the nuclear family) have broken down, giving individuals more freedom but also more uncertainty.

Key Concepts: Family diversity, individualisation, personal choice, life course, negotiated families, pure relationship (Giddens), pluralism.

Evaluation: Critics argue Postmodernism exaggerates the extent of choice, as structural factors (class, ethnicity, gender) still constrain family options. The New Right argues that excessive choice has led to instability and social breakdown.

Named Example Bank

Candidates must include specific named examples, statistics, and dates to achieve top marks. Here are five essential examples:

-

Divorce Reform Act 1969: Introduced 'irretrievable breakdown' as the sole grounds for divorce, leading to a dramatic rise in divorce rates. By 1993, divorce rates peaked at approximately 165,000 per year in England and Wales.

-

Rapoport and Rapoport (1982): Identified five types of family diversity (Cultural, Life-stage, Organisational, Generational, Social class), providing a comprehensive framework for analysing family structures.

-

Charles Murray (1990s): New Right theorist who argued that the rise of lone-parent families, particularly among the working class, had created an 'underclass' characterised by welfare dependency, crime, and educational underachievement.

-

Ann Oakley (1974): Feminist sociologist who identified the 'dual burden' faced by women, who perform both paid work and the majority of domestic labour. Her research showed that even in dual-earner families, women performed an average of 77 hours of housework per week, compared to men's 12 hours.

-

Marriage (Same-Sex Couples) Act 2013: Legalised same-sex marriage in England and Wales, enabling same-sex couples to marry and adopt children with the same legal rights as heterosexual couples. By 2021, there were approximately 212,000 same-sex couple families in the UK.

Synoptic Links

Family diversity connects to multiple areas of the AQA GCSE Sociology specification. Examiners reward candidates who make these connections.

Link to Social Stratification

Family diversity is closely linked to social class. Middle-class families are more likely to be dual-earner nuclear families with high levels of cultural and economic capital, while working-class families are more likely to rely on extended kin networks and experience economic insecurity. The New Right's concept of an 'underclass' of welfare-dependent lone-parent families is contested by sociologists who argue that structural factors (unemployment, low wages) are the real cause of poverty.

Link to Gender and Identity

Changing gender roles have been a major driver of family diversity. The rise of feminism, women's increased participation in education and employment, and legal reforms (Equal Pay Act 1970, Sex Discrimination Act 1975) have given women greater economic independence and choice. This has led to delayed marriage, increased divorce, and the growth of lone-parent and dual-earner families.

Link to Social Policy

Government policies have both reflected and shaped family diversity. Pro-natalist policies (e.g., child benefit, maternity leave) encourage childbearing, while policies such as tax breaks for married couples (advocated by the New Right) attempt to promote the nuclear family. The introduction of civil partnerships and same-sex marriage demonstrates state recognition of diverse family forms.

Exam Technique

Mastering exam technique is essential for translating knowledge into marks. Here's how to approach different question types.

Time Per Mark

Approximately 1 minute per mark, plus 2-3 minutes planning time for longer questions. For a 12-mark question, allocate 15 minutes total (2-3 minutes planning, 12 minutes writing).

Question Approach

AQA Sociology questions use specific command words that signal what is required. Candidates must decode these carefully.

Answer Structure

4-Mark 'Describe' Questions: Provide two developed features with supporting information. For example, 'Describe two ways in which family structures have become more diverse' requires two distinct points, each with elaboration (e.g., specific family types, statistics, or examples).

4-Mark 'Explain' Questions: Provide one clear explanation with a developed chain of reasoning. For example, 'Explain one reason for the increase in lone-parent families' requires a cause (e.g., Divorce Reform Act 1969) linked to an effect (easier divorce) with a clear explanation of the mechanism.

12-Mark 'Discuss How Far' Questions: These require a balanced argument with evidence on both sides, followed by a clear judgement. Structure: Introduction outlining the debate → Paragraph 1 (arguments supporting the statement, with evidence) → Paragraph 2 (counter-arguments, with evidence) → Paragraph 3 (evaluation and synthesis) → Conclusion (clear judgement on 'how far').

Common Pitfalls

- Narrative without analysis: Simply describing family types without explaining causes or evaluating perspectives.

- Vague knowledge lacking specific dates/names: Examiners reward precision. Always include named theorists, legislation, and statistics.

- Confusing New Right with Functionalism: While both favour the nuclear family, they are distinct perspectives with different focuses.

- Ignoring the Item: In 12-mark questions, candidates must explicitly reference and apply the provided Item to support or refute the statement.

- Failing to reach a judgement: 'Discuss how far' questions require a clear conclusion on the extent of agreement.

Command Word Strategies

Describe: Provide factual information with supporting detail. No evaluation required.

Explain why: Identify causes or reasons and explain the mechanism linking cause to effect. Use connective language ('This led to...', 'As a result...', 'Consequently...').

Discuss how far you agree: Present a balanced argument with evidence on both sides, then reach a clear judgement on the extent of agreement. Use the Item as a 'hook' to anchor your argument.

Using the Item: The Item is a short stimulus (2-3 sentences) provided in 12-mark questions. Candidates must quote or paraphrase the Item and link it to sociological concepts. For example, if the Item mentions 'changing laws', link this to the Divorce Reform Act 1969 and explain its impact on family diversity.