Study Notes

Overview

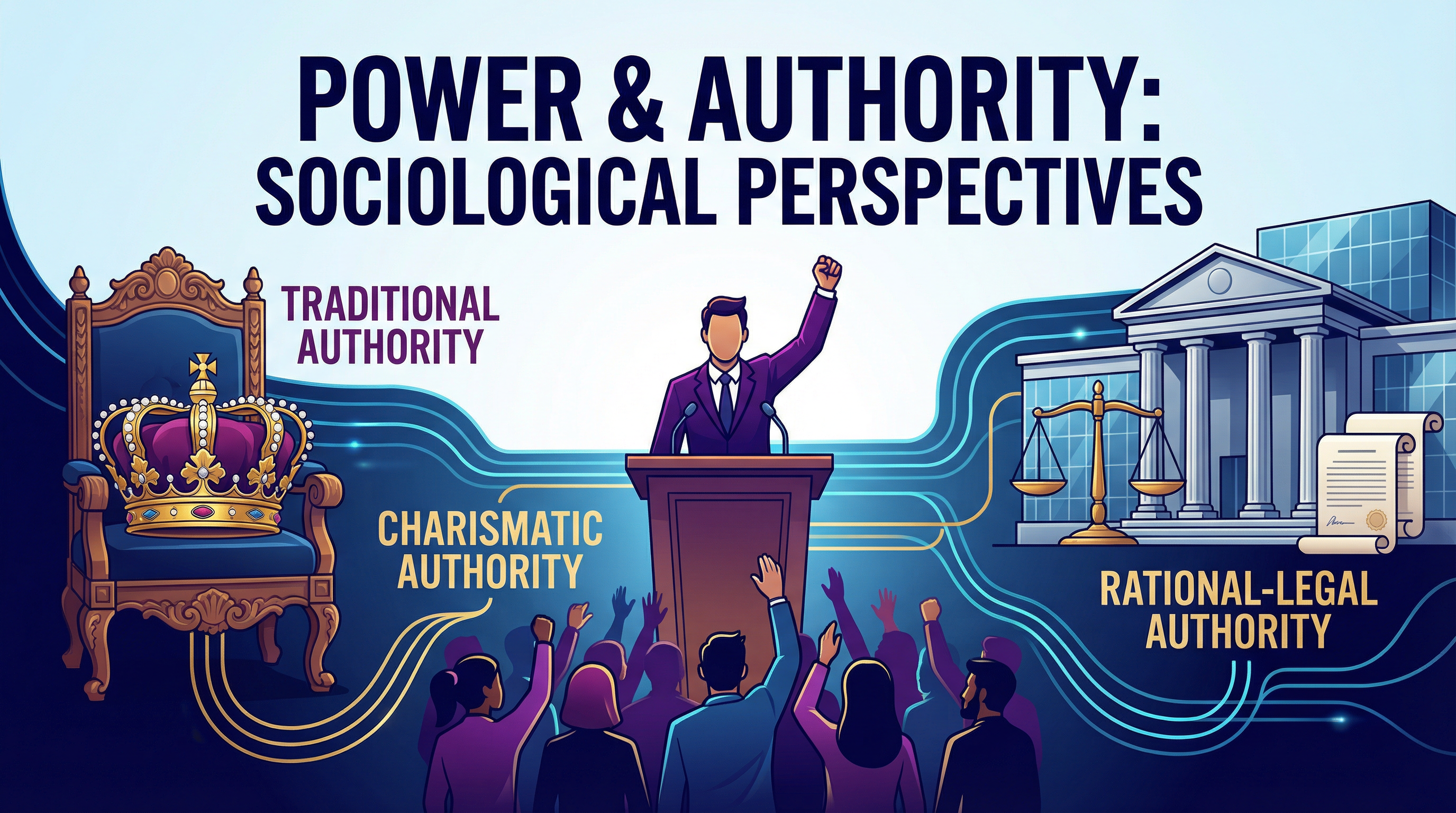

Power and Authority sits at the heart of sociological inquiry into social differentiation and stratification. This topic requires candidates to distinguish between power as coercion and authority as legitimate, consensual power. Max Weber's typology of authority—Traditional, Charismatic, and Rational-Legal—provides the analytical framework examiners expect candidates to deploy with precision. Beyond Weber, candidates must evaluate competing theoretical perspectives on the State: Marxists argue it is an instrument of class oppression serving the bourgeoisie, while Pluralists contend it represents democratic participation with power distributed among competing interest groups. Voting behaviour and pressure groups extend this analysis into contemporary political participation, where class dealignment and issue-based voting challenge traditional patterns. Examiners award credit for sociological analysis that applies theoretical perspectives to real-world examples, uses precise terminology, and evaluates rather than merely describes.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Power vs Authority: The Fundamental Distinction

Power is the ability of an individual or group to get others to do what they want, even if there is resistance. Power can be exercised through coercion—using force or threats to compel obedience. A criminal threatening someone with violence exemplifies coercive power. In contrast, authority is power that people accept as legitimate because they believe it is right and fair. Authority operates through consent rather than force. People willingly obey those in authority because they recognise their right to lead. This distinction is critical: examiners penalise candidates who conflate power and authority or fail to demonstrate understanding of legitimacy and consent.

Weber argued that authority, unlike raw power, is embedded in social structures and relationships. We tend to be deferential towards those with authority—teachers, police officers, judges—because we accept the legitimacy of their position. This acceptance transforms power from coercion into authority. Candidates must demonstrate this understanding explicitly in exam responses, using phrases like "legitimate power" and "consensual obedience" to signal sophisticated sociological thinking.

Weber's Three Types of Authority

Max Weber (1947) identified three ideal types of authority, each based on different sources of legitimacy. Candidates must be able to name, define, and exemplify each type with precision.

Traditional Authority

Traditional Authority is based on custom, tradition, and inheritance. People obey because "things have always been that way." Legitimacy derives from long-established practices and beliefs passed down through generations. Weber used the British monarchy as a classic example: the royal bloodline determines who becomes king or queen based on birth right, not merit or election. Although the monarchy's political power is limited in modern Britain, people still accept the monarch's authority through tradition and national custom, evidenced by public participation in coronations and royal weddings.

A specific example candidates should cite: before 2015, a male heir inherited the British throne even if he had an older sister, demonstrating how traditional gendered authority privileged male succession. The Succession to the Crown Act 2013 (implemented 2015) ended this practice, showing how traditional authority can evolve. In Victorian Britain, men held authority as heads of household and dominated politics, reflecting patriarchal traditional authority. Candidates should contrast this with systems like the United States, where the president is elected rather than born into power—an example of rational-legal authority.

Charismatic Authority

Charismatic Authority is based on a leader's personal qualities, inspiration, and ability to attract followers. People obey because they are inspired by the leader's vision, personality, or perceived exceptional abilities, not because of tradition or law. Charismatic leaders often emerge during times of crisis or social change, when existing authority structures are challenged or weakened. However, this type of authority is often temporary—it depends on the leader's personal appeal and may fade when they die, lose popularity, or fail to deliver on promises.

Candidates should cite specific named examples:

- Martin Luther King Jr inspired millions through his leadership of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, using powerful oratory and moral authority to challenge racial segregation.

- Mahatma Gandhi led India's struggle for independence from British colonial rule through peaceful protest and civil disobedience, drawing authority from his personal commitment to non-violence.

- Jesus inspired followers through faith, teaching, and perceived divine connection, establishing a religious movement that persists two millennia later.

- Contemporary examples include figures like Greta Thunberg in climate activism, whose youth and moral conviction have inspired global movements.

Examiners reward candidates who explain why charismatic authority is unstable: it is not institutionalised or embedded in formal structures, so it often collapses after the leader's death unless it is routinised into traditional or rational-legal forms.

Rational-Legal Authority

Rational-Legal Authority is the most common form of authority in modern societies. It is based on rules, laws, and formal procedures, not on tradition or personality. People obey because they accept the laws or rules that give power to leaders, and because they believe in the legitimacy of the legal system itself. This type of authority operates within bureaucracies—organisations with clear structures, hierarchies, and regulations designed to ensure predictability, efficiency, and fairness.

Leaders with rational-legal authority gain power through legal means, such as elections, and can lose it if they break the rules or laws that grant them authority. This makes rational-legal authority more stable and predictable than charismatic authority, and more adaptable than traditional authority.

Candidates should cite specific examples:

- A prime minister is elected through democratic processes and must follow the law and constitution. If they violate these, they can be removed from office.

- Police officers and judges have authority because the law gives them the power to enforce rules and administer justice. Their authority derives from their legal role, not their personal qualities.

- In prisons, officers have legal authority to discipline inmates according to regulations, and inmates generally accept this authority as legitimate within the legal framework.

- Teachers have rational-legal authority based on school rules and regulations, though they may also exercise charismatic authority if they inspire students.

Mixing Types of Authority

Weber recognised that in real life, leaders often combine different types of authority. Teachers have rational-legal authority based on school rules and their formal position, but effective teachers may also have charismatic authority if they inspire and motivate students through their personality and teaching style. Politicians often use charisma to win elections and build popular support, but once in power, they must operate within legal frameworks and institutional constraints, exercising rational-legal authority. The British monarchy combines traditional authority (inherited position) with elements of charismatic authority (public affection for particular monarchs) and rational-legal authority (constitutional role defined by law).

Competing Theoretical Perspectives on the State

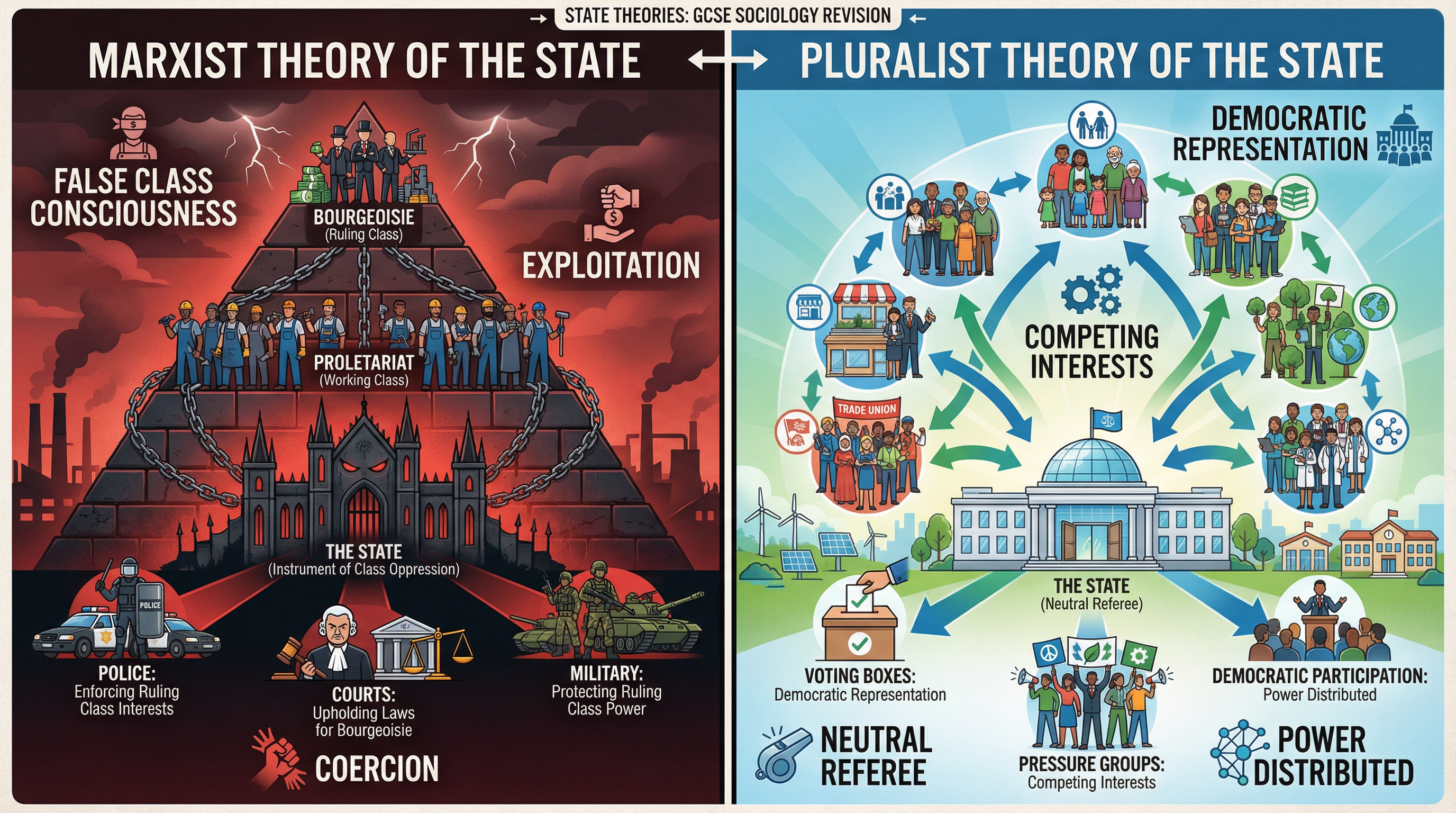

Marxist Theory of the State

Marxist sociologists argue that the State is an instrument of class oppression. According to Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, "the state is an organ of class rule, an organ for the oppression of one class by another." The State serves the interests of the bourgeoisie (the ruling capitalist class who own the means of production) to oppress and exploit the proletariat (the working class who sell their labour). The State is not neutral; it protects capitalist interests through institutions like the police, courts, and military, which enforce laws that maintain private property and capitalist relations of production.

Marxists identify several mechanisms through which the State maintains bourgeois power:

- Coercion: The State uses police and military force to suppress working-class resistance, such as strikes or protests.

- Ideological control: The State uses education, media, and religion to promote false class consciousness—a condition where workers are unaware of their exploitation and accept the capitalist system as natural and inevitable.

- Legal frameworks: Laws protect private property and capitalist interests, criminalising actions that threaten the ruling class (e.g., theft, trespassing) while permitting exploitation through wage labour.

Antonio Gramsci, a Marxist theorist, developed the concept of hegemony—the cultural dominance of the ruling class. The ruling class maintains power not only through coercion but also through consent, by making their ideas appear as "common sense." Workers accept capitalism because they have been socialised to believe in its legitimacy.

Candidates should use this perspective to argue: "Some sociologists, particularly Marxists, argue the State is an instrument of class oppression, serving the interests of the bourgeoisie to exploit the proletariat. The State uses institutions like the police and courts to enforce ruling class interests, while promoting false class consciousness through education and media."

Pluralist Theory of the State

Pluralist sociologists argue that the State represents democratic representation of diverse interests. In a pluralist system, multiple groups compete for influence, and power is distributed among various interest groups rather than concentrated in one class. The State acts as a neutral referee between competing groups, mediating conflicts and making decisions that reflect the balance of interests in society.

Pluralists emphasise several features of democratic participation:

- Elections: Citizens choose representatives through free and fair elections, ensuring government accountability.

- Pressure groups: Between elections, citizens participate in politics through pressure groups, which lobby government, raise awareness, and hold officials accountable.

- Checks and balances: Institutional mechanisms (e.g., separation of powers, independent judiciary) prevent any single group from dominating.

- Open access: The democratic process is, in principle, open and accessible to all, allowing marginalised groups to organise and influence policy.

Pluralists acknowledge that some groups have more resources and influence than others, but they argue that no single group can dominate permanently. Power is dispersed, and different groups win on different issues.

Candidates should use this perspective to argue: "However, Pluralist sociologists argue the State represents democratic participation, with power distributed among various groups. The State acts as a neutral referee, and elections and pressure groups enable citizens to influence policy."

Evaluation: Marxist vs Pluralist Debate

Examiners reward candidates who evaluate these perspectives rather than simply describing them. A strong evaluation might argue:

- In favour of Marxism: Evidence of class inequality, corporate lobbying, and the disproportionate influence of wealthy elites suggests the State does serve ruling class interests. The 2008 financial crisis, where governments bailed out banks while imposing austerity on workers, supports the Marxist view.

- In favour of Pluralism: The existence of welfare states, labour rights, and environmental regulations suggests the State does respond to diverse interests, not just the bourgeoisie. Pressure groups like trade unions have successfully influenced policy.

- Synthesis: Some sociologists, like Miliband and Poulantzas, argue the State has "relative autonomy"—it serves long-term capitalist interests but can make concessions to workers to maintain social stability.

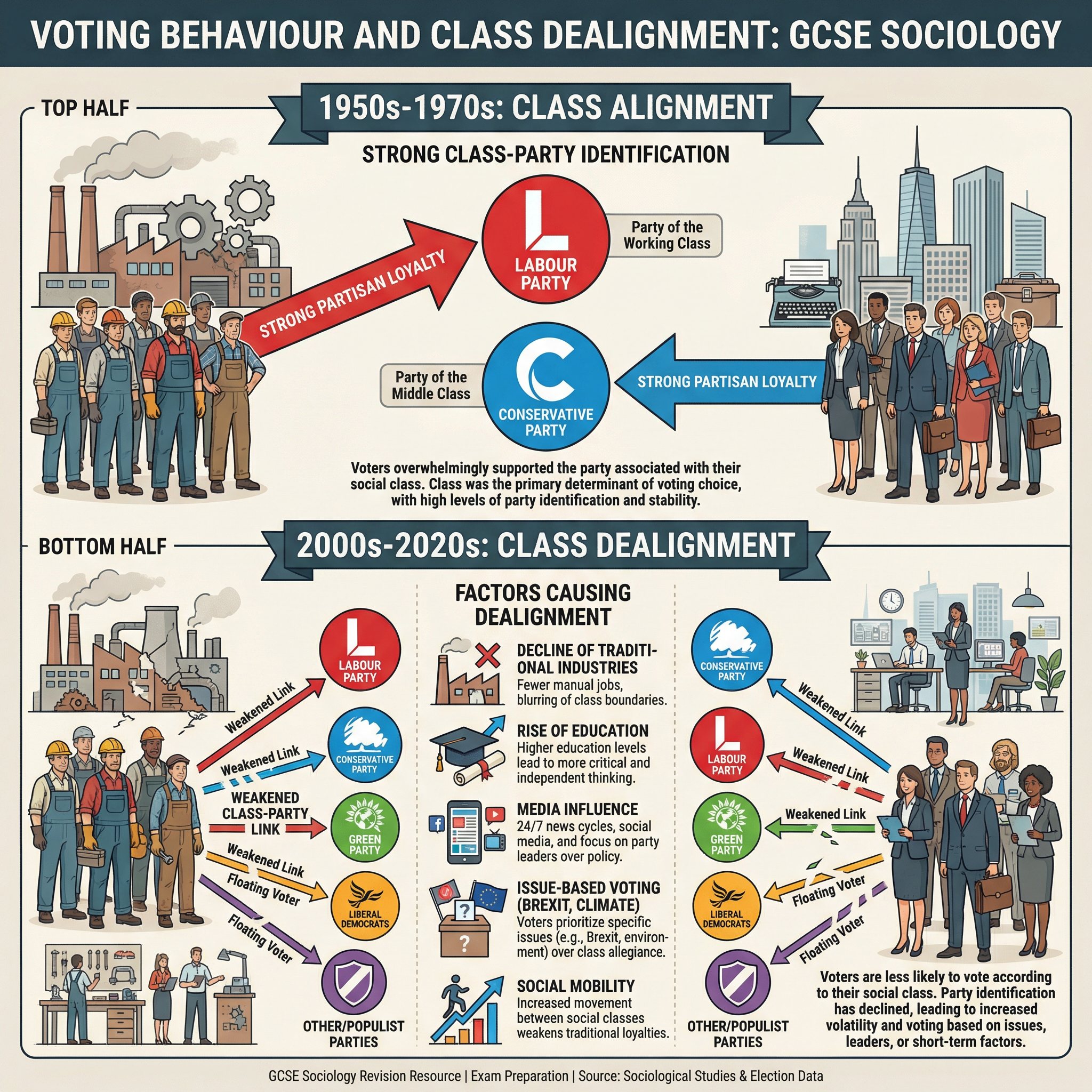

Voting Behaviour: Class Alignment and Dealignment

Class Alignment (1950s–1970s)

From the 1950s to the 1970s, British voting behaviour exhibited strong class alignment. The working class (manual workers, lower-income groups) overwhelmingly voted Labour, while the middle class (professionals, managers, higher-income groups) predominantly voted Conservative. This pattern reflected partisan alignment—voters identified strongly with a particular political party based on their class identity, and this loyalty remained stable over time.

Sociologists explained this pattern through the concept of class consciousness: workers saw Labour as the party representing their economic interests (higher wages, welfare, nationalisation), while the middle class saw the Conservatives as protecting their interests (lower taxes, private property, free markets). Class was the primary determinant of voting choice, with high levels of party identification and stability.

Class Dealignment (2000s–2020s)

Since the 1980s, and accelerating in the 2000s and 2010s, British voting behaviour has exhibited class dealignment—social classes are voting in far fewer numbers for the political party they used to traditionally vote for. The link between social class and voting behaviour has weakened significantly. Voters are less likely to identify with a single party throughout their lives, and voting has become more volatile and unpredictable.

Sociologists identify several factors causing dealignment:

- Decline of traditional industries: The collapse of manufacturing, mining, and heavy industry in the 1980s and 1990s reduced the size of the traditional working class, weakening the social base for Labour's class-based appeal.

- Rise of education and social mobility: Increased access to higher education has created a more diverse and fluid class structure, with individuals moving between classes and developing more complex political identities.

- Media influence: The rise of 24-hour news, social media, and targeted political advertising has shifted focus from class-based appeals to personality, image, and specific issues.

- Issue-based voting: Voters increasingly prioritise specific issues—such as Brexit, climate change, immigration, or the NHS—over class loyalty. The 2016 Brexit referendum, for example, cut across traditional class lines, with working-class Leave voters and middle-class Remain voters defying class alignment.

- Partisan dealignment: Voters are less likely to identify strongly with any party, leading to increased support for third parties (Liberal Democrats, Green Party, UKIP/Brexit Party) and greater electoral volatility.

Factors Influencing Voting Behaviour (Sociological Analysis)

Candidates must demonstrate that voting behaviour is shaped by multiple sociological factors, not just class:

- Age: Younger voters (18–34) are more likely to vote Labour or for progressive parties, while older voters (65+) are more likely to vote Conservative. This reflects generational differences in values, economic security, and socialisation.

- Gender: Historically, men and women voted differently (e.g., women were more likely to vote Conservative in the 1950s–1970s), but the gender gap has narrowed. However, specific issues (e.g., abortion, childcare) can create gendered voting patterns.

- Ethnicity: Ethnic minorities in the UK are significantly more likely to vote Labour, reflecting Labour's historical support for anti-racism, multiculturalism, and welfare policies that benefit marginalised communities.

- Education: Higher education is correlated with support for progressive social policies (e.g., LGBTQ+ rights, environmentalism) and, in recent elections, with voting Labour or Liberal Democrat.

- Region: The North-South divide remains significant, with the North, Wales, and Scotland historically more Labour-supporting, and the South (especially the South East) more Conservative. However, the 2019 election saw Labour lose traditional Northern seats to the Conservatives, complicating this pattern.

- Media influence: Newspapers, television, and social media shape public opinion and voting behaviour. The dominance of right-wing newspapers (e.g., Daily Mail, The Sun) in the UK has been argued to benefit the Conservative Party.

Examiners reward candidates who analyse voting behaviour sociologically, explaining why people vote as they do, rather than simply describing electoral outcomes.

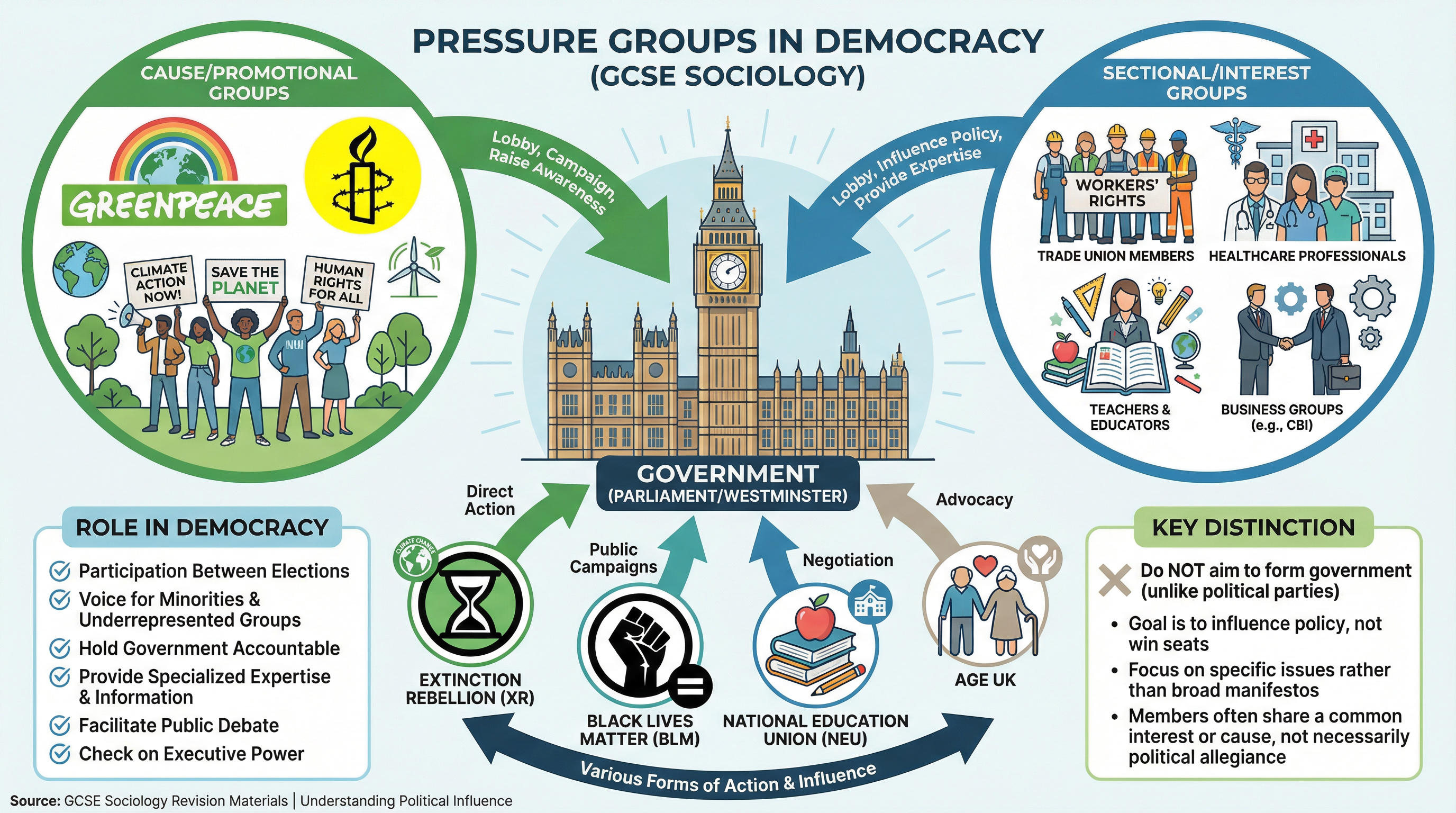

Pressure Groups and Political Participation

Definition and Key Distinction

Pressure groups are organisations that seek to influence government policy without seeking to form a government themselves. This is the key distinction candidates must make: pressure groups do NOT aim to form a government or win seats in Parliament (unlike political parties). Their goal is to influence policy, not to exercise direct political power. Pressure groups focus on specific issues or represent particular sections of society, and members often share a common interest or cause rather than a broad political ideology.

Types of Pressure Groups

-

Cause/Promotional Groups: These groups promote a particular cause or issue that is not directly related to members' self-interest. They campaign for broader social, environmental, or moral goals. Examples include:

- Greenpeace: Environmental protection and climate action

- Amnesty International: Human rights and opposition to torture and the death penalty

- Stonewall: LGBTQ+ rights and equality

-

Sectional/Interest Groups: These groups represent specific sections of society and campaign for the interests of their members. Examples include:

- Trade unions (e.g., National Education Union, UNISON): Workers' rights, pay, and conditions

- Professional associations (e.g., British Medical Association): Interests of doctors and healthcare professionals

- Business groups (e.g., Confederation of British Industry): Interests of businesses and employers

Role in Democracy

Pressure groups play a vital role in democratic participation:

- Participation between elections: Pressure groups enable citizens to engage in politics continuously, not just during elections. This deepens democratic engagement.

- Voice for minorities and underrepresented groups: Pressure groups give voice to interests that may be ignored by mainstream political parties, such as disability rights, animal welfare, or specific regional concerns.

- Hold government accountable: Pressure groups scrutinise government policy, expose failures, and campaign for change, acting as a check on executive power.

- Provide expertise and information: Pressure groups often have specialist knowledge and can inform policymakers about the practical implications of proposed policies.

- Raise awareness of issues: Pressure groups use campaigns, protests, and media coverage to bring issues to public attention and shape the political agenda.

Contemporary Examples for AO2 Application

Candidates should cite specific, contemporary examples to demonstrate AO2 (application):

- Extinction Rebellion (XR): A cause group using direct action (e.g., road blockades, occupations) to demand urgent government action on climate change. XR has raised awareness but also faced criticism for disruptive tactics.

- Black Lives Matter (BLM): A cause group campaigning for racial justice and police reform, particularly in response to deaths of Black individuals in police custody. BLM has influenced public discourse and policy debates on institutional racism.

- National Education Union (NEU): A sectional group representing teachers, campaigning on issues like pay, workload, and school funding. The NEU has organised strikes and lobbied government.

- Age UK: A cause/sectional group advocating for the rights and welfare of elderly people, campaigning on issues like pensions, social care, and age discrimination.

Criticisms of Pressure Groups

Examiners reward candidates who evaluate the role of pressure groups critically:

- Unequal power and resources: Some pressure groups (e.g., wealthy corporations, well-funded charities) have far more resources, access to policymakers, and media influence than others (e.g., small community groups). This creates inequality in democratic participation.

- Narrow interests: Sectional groups may represent narrow interests that conflict with the public good. For example, a trade union may campaign for higher wages that could lead to job losses or higher prices.

- Disruptive tactics: Some pressure groups use tactics (e.g., road blockades, occupations) that disrupt public life and may undermine democratic norms.

- Lack of accountability: Pressure groups are not democratically elected and are not accountable to the public in the same way as elected representatives. They may claim to represent public opinion but lack a democratic mandate.

Key Sociological Concepts

Oligarchy

Oligarchy refers to rule by a small elite group, where power is concentrated in the hands of a few. Robert Michels developed the "Iron Law of Oligarchy", arguing that all organisations, even democratic ones, tend towards oligarchy. Leaders accumulate power, knowledge, and resources, making them difficult to challenge or replace. This concept can be applied to political parties, pressure groups, and even democratic states, suggesting that true democracy is difficult to achieve.

Patriarchy

Patriarchy is a system of society where men hold power and women are excluded from political, economic, and social institutions. Feminist sociologists argue that the State perpetuates patriarchal power structures, with men dominating Parliament, the judiciary, and corporate leadership. Before women gained the vote (1918 for women over 30; 1928 for women over 21), the British State was explicitly patriarchal. Even today, feminists argue that gender inequality persists in political representation and policy priorities.

False Class Consciousness (Marxist)

False class consciousness is a Marxist concept referring to a condition where workers are unaware of their exploitation and accept the capitalist system as natural and inevitable. The ruling class uses ideology—through media, education, and religion—to maintain this false consciousness, preventing workers from recognising their true class interests and organising for revolutionary change. Marxists argue that achieving true class consciousness (awareness of exploitation and collective action) is necessary for overthrowing capitalism.

Hegemony (Gramsci)

Hegemony refers to the cultural dominance of the ruling class. Antonio Gramsci, a Marxist theorist, argued that the ruling class maintains power not only through coercion (police, military) but also through consent, by making their ideas appear as "common sense." People accept capitalism, inequality, and ruling class authority because they have been socialised to believe in their legitimacy. Hegemony is maintained through institutions like schools, media, and religion, which promote ruling class ideology.

Exam Technique and Command Word Strategies

Time Allocation

Candidates should allocate approximately 1 minute per mark, plus planning time for longer questions. For example:

- A 4-mark "Describe" question should take approximately 4–5 minutes.

- A 12-mark "Explain why" question should take approximately 12–15 minutes, including planning.

- A 20-mark "Discuss" or "How far do you agree" question should take approximately 20–25 minutes, including planning.

Do not over-write for low-tariff questions. Save detailed analysis and evaluation for higher-mark questions.

Command Word Strategies

Describe (typically 2–4 marks): Provide two developed features with supporting information. Do not analyse or evaluate—simply identify and explain key features. For example:

- "Describe two features of Traditional Authority." Answer: "One feature of Traditional Authority is that it is based on custom and inheritance, such as the British monarchy where succession is determined by royal bloodline. Another feature is that people obey because 'things have always been that way,' accepting authority through long-established tradition."

Explain why (typically 8–12 marks): Provide multiple explained causes or reasons, linked together. Use PEEL structure (Point, Evidence, Explanation, Link). For example:

- "Explain why class dealignment has occurred." Answer: "One reason for class dealignment is the decline of traditional industries. The collapse of manufacturing and mining in the 1980s reduced the size of the traditional working class, weakening Labour's social base (Point). For example, the closure of coal mines and steel plants led to mass unemployment in former industrial areas (Evidence). This meant fewer workers identified with the working class and voted Labour based on class loyalty (Explanation). This contributed to a broader weakening of the class-party link (Link to next point)."

Discuss / How far do you agree (typically 16–20 marks): Provide a balanced argument with evidence on both sides, and reach a clear judgement. Structure your response as:

- Introduction: Briefly outline the debate and state your criteria for judgement.

- Argument 1: Present one perspective (e.g., Marxist view) with evidence and examples.

- Counter-argument: Present an opposing perspective (e.g., Pluralist view) with evidence and examples.

- Evaluation: Weigh the arguments, consider their strengths and weaknesses, and reach a sustained judgement.

For example:

- "Discuss the view that the State is an instrument of class oppression." Answer: "Some sociologists, particularly Marxists, argue the State is an instrument of class oppression... [develop argument with evidence]. However, Pluralist sociologists argue the State represents democratic participation... [develop counter-argument with evidence]. Overall, while there is evidence of ruling class influence, the existence of welfare policies and labour rights suggests the State is not purely an instrument of oppression, but has relative autonomy... [reach judgement]."

How useful (source questions, typically 6–8 marks): Analyse content (what the source tells us), provenance (who created it, when, why), usefulness (what it reveals), and limitations (what it doesn't tell us, bias, purpose). Compare sources if multiple sources are provided. For example:

- "How useful is Source A for an enquiry into pressure groups?" Answer: "Source A is useful because it provides evidence of [content analysis]. The provenance adds to its usefulness because [author/date/type]. However, its usefulness is limited by [what it doesn't tell us / bias / purpose]."

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Narrative without analysis: Do not simply describe events or concepts. Examiners want analysis—explain why, how, and with what consequences.

- Vague knowledge lacking specific dates, names, or statistics: Always cite specific examples. Instead of "charismatic leaders inspire people," write "Martin Luther King Jr inspired millions during the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s."

- Ignoring provenance in source questions: Always analyse who created the source, when, and why. This affects its usefulness and reliability.

- Conflating pressure groups with political parties: Remember, pressure groups do NOT aim to form a government.

- Purely civics-based answers: Provide sociological analysis, not just descriptions of how institutions work. Explain why people vote, not just how voting works.

- Asserting Traditional Authority is extinct: Traditional Authority is diminished or evolved, but it still exists (e.g., the monarchy).

- Assuming universal representation in democracy: Critique the democratic process by considering exclusion, inequality, and barriers to participation.