Study Notes

Overview

Welcome to your deep dive into Group 1 of the periodic table, the alkali metals. This topic is a cornerstone of GCSE Chemistry, frequently appearing in exams because it perfectly tests your understanding of periodic trends and the link between atomic structure and chemical properties. In this guide, we will explore why these soft, silvery metals are so keen to react and how their behaviour changes as we move down the group from Lithium to Francium. You will learn to explain these trends using precise scientific language about electron shells, shielding, and nuclear attraction—the exact vocabulary that earns marks. We will also cover the characteristic reactions with water, oxygen, and halogens, ensuring you can provide the detailed observations and balanced symbol equations that examiners are looking for. Typical exam questions range from short-answer 'describe' tasks to longer 'explain' questions worth up to 6 marks, so a solid grasp of this topic is essential for success.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Atomic Structure and the Single Outer Electron

The defining feature of a Group 1 element is its atomic structure. Every alkali metal has one electron in its outermost shell. This lone electron is the star of the show; its desire to leave the atom dictates the entire chemistry of the group. Because metals react by losing electrons to form positive ions, having only one electron to lose makes this process energetically favourable. Losing this single electron gives the alkali metal atom the stable electronic structure of a noble gas. For example, Sodium (Na) has the electron configuration 2.8.1. By losing one electron, it becomes a Sodium ion (Na+) with the configuration 2.8, the same as Neon. This drive for stability is why the alkali metals are so reactive.

Concept 2: The Trend in Reactivity

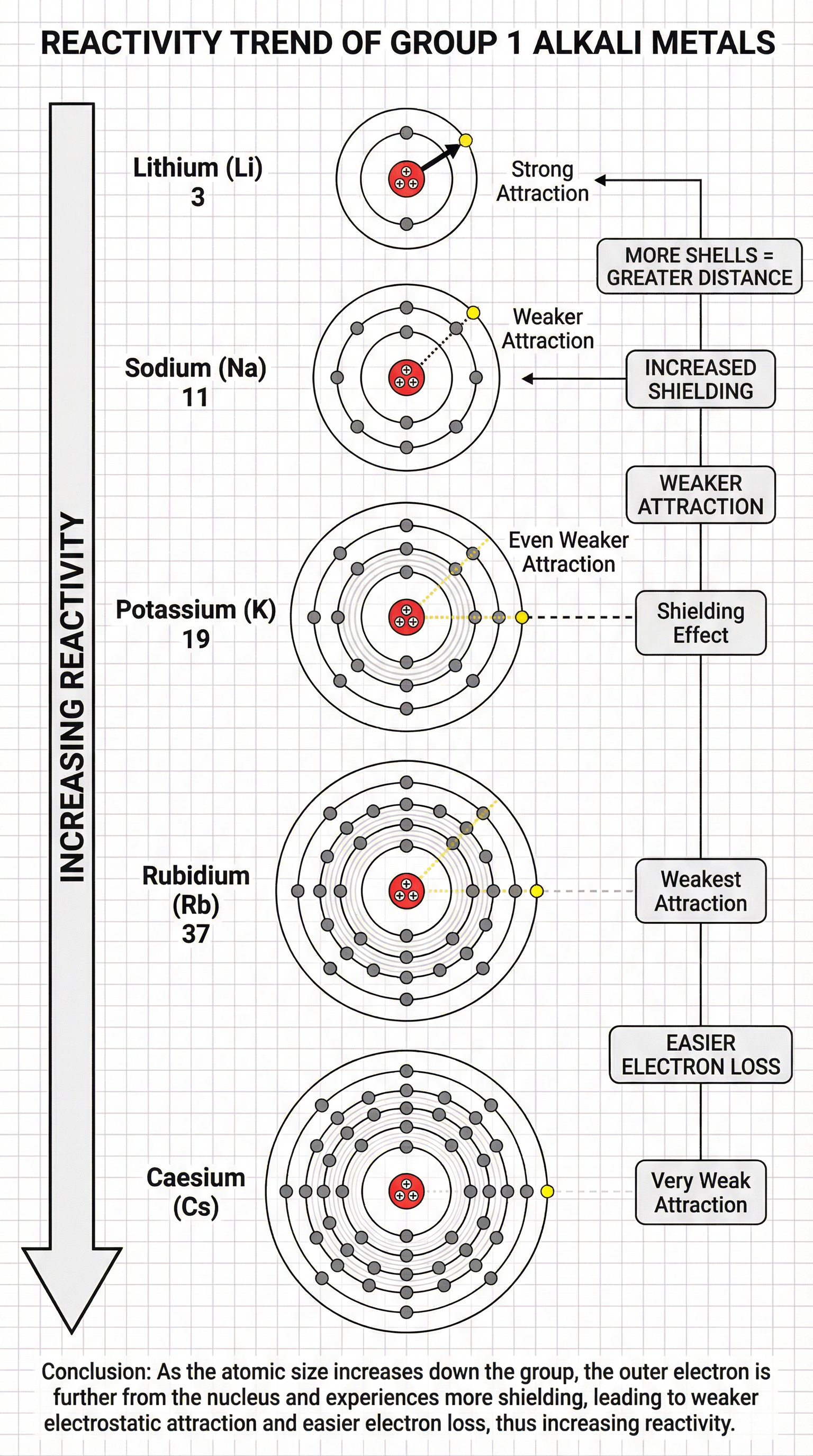

The most important trend to understand is that reactivity increases as you go down Group 1. Lithium is reactive, Sodium is more so, Potassium is even more vigorous, and so on. To explain this, you must refer to three key factors: atomic radius, electron shielding, and the electrostatic attraction between the nucleus and the outer electron.

- Atomic Radius Increases: As you move down the group, each element has an additional electron shell. This means the outer electron is progressively further away from the nucleus.

- Electron Shielding Increases: The inner shells of electrons 'shield' the outer electron from the positive pull of the nucleus. The more shells there are, the greater the shielding effect.

- Weaker Electrostatic Attraction: The combination of increased distance and increased shielding means the electrostatic force of attraction between the positive nucleus and the single, negative outer electron becomes weaker.

Because the outer electron is held less tightly, it is lost more easily. Since the reaction involves losing this electron, less energy is required to remove it, and the element is therefore more reactive. Candidates who can articulate this four-step argument (Size/Distance -> Shielding -> Attraction -> Ease of electron loss) will be awarded full marks.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

While this topic is less about mathematical formulas, it is heavy on chemical equations. You must be able to write balanced symbol equations for the reactions of alkali metals. The state symbols are crucial for gaining full credit.

General Equation with Water:

2M(s) + 2H₂O(l) → 2MOH(aq) + H₂(g)

Where 'M' represents any Group 1 metal.

- Example (Sodium):

2Na(s) + 2H₂O(l) → 2NaOH(aq) + H₂(g) - Example (Potassium):

2K(s) + 2H₂O(l) → 2KOH(aq) + H₂(g)

General Equation with Chlorine:

2M(s) + Cl₂(g) → 2MCl(s)

- Example (Lithium):

2Li(s) + Cl₂(g) → 2LiCl(s)

General Equation with Oxygen:

4M(s) + O₂(g) → 2M₂O(s)

- Example (Sodium):

4Na(s) + O₂(g) → 2Na₂O(s)

Practical Applications

This topic is directly linked to a required practical where you observe the reactions of Lithium, Sodium, and Potassium with water. Examiners will test your knowledge of the apparatus, method, and, most importantly, the observations.

Apparatus: Large trough or beaker, safety screen, forceps, universal indicator, scalpel, tile.

Method:

- Fill a beaker with water and add a few drops of universal indicator.

- Using forceps, place a small, freshly cut piece of Lithium onto the surface of the water.

- Observe the reaction from behind a safety screen.

- Record all observations.

- Repeat the experiment with Sodium and then Potassium, ensuring the water is replaced each time.

Expected Results & Observations: Candidates must be able to distinguish the observations for each metal.

{{asset:alkali_water_reactions.png