Study Notes

Overview

Crude oil is the lifeblood of modern industry, but in its raw state, it's a sludgy, complex mixture of little use. This topic, a cornerstone of organic chemistry, delves into how we refine this finite resource into a vast array of valuable products. For your Edexcel GCSE, you'll be expected to demonstrate a clear understanding of fractional distillation, the physical process used to separate crude oil. A significant portion of marks, typically 40% for AO1 (knowledge) and 40% for AO2 (application), are awarded for describing this process and explaining the properties of the resulting fractions. You'll connect the microscopic world of molecules—specifically, the length of hydrocarbon chains—to the macroscopic properties you observe, like viscosity and flammability. Expect exam questions to range from simple definitions to 6-mark extended responses requiring you to link chain length, intermolecular forces, and boiling points in a coherent narrative.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Crude Oil as a Mixture

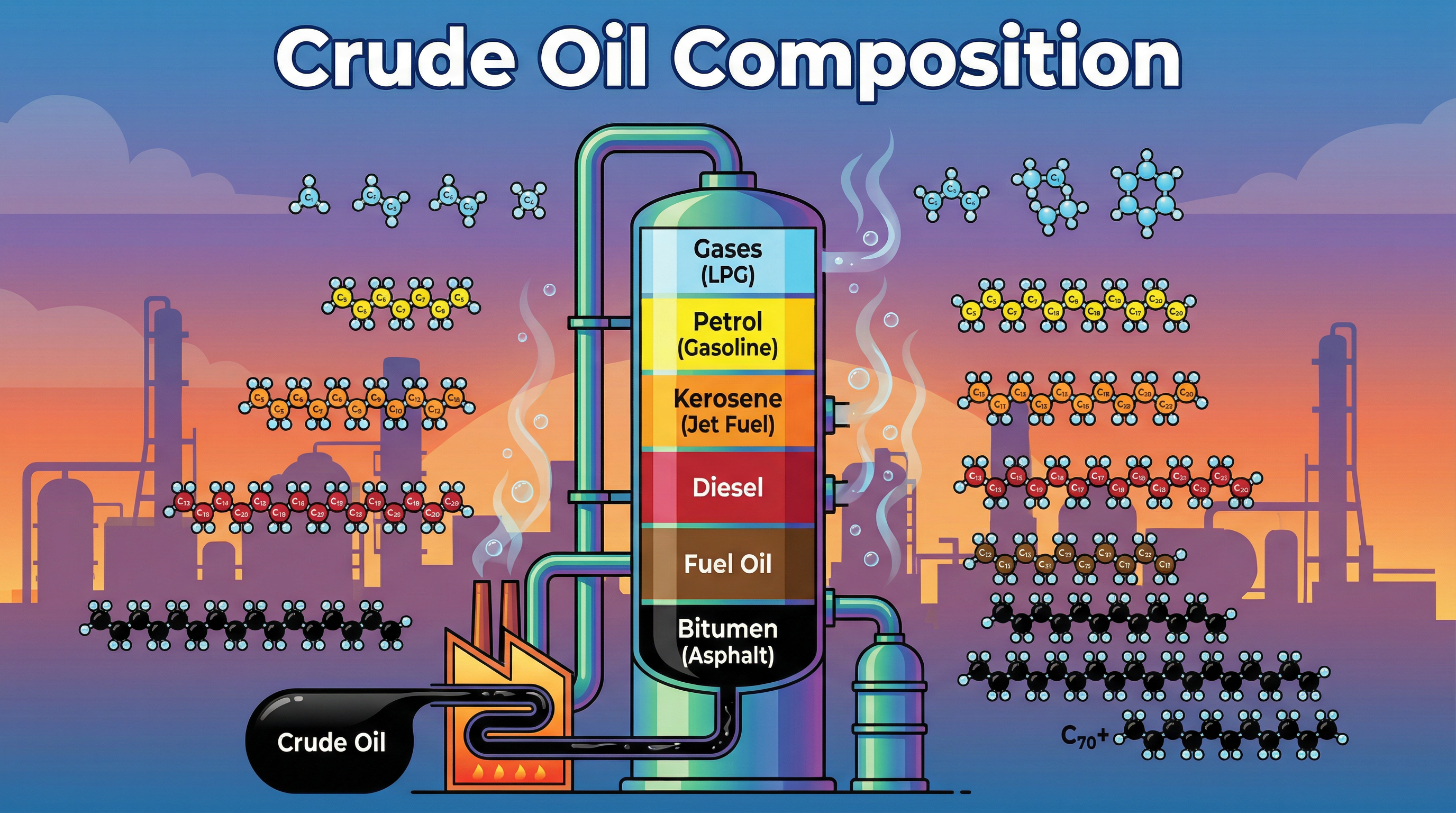

Crude oil is a naturally occurring, unrefined petroleum product composed of hydrocarbon deposits. For your exam, the two key points to remember are that it is a finite resource (meaning it is non-renewable and will run out) and a complex mixture of hydrocarbons. A 'mixture' means the different components (the hydrocarbons) are not chemically bonded together. This is a critical point because it means we can separate them based on their physical properties, which is exactly what fractional distillation does. The hydrocarbons in crude oil are predominantly alkanes, a family of saturated hydrocarbons.

Concept 2: Fractional Distillation

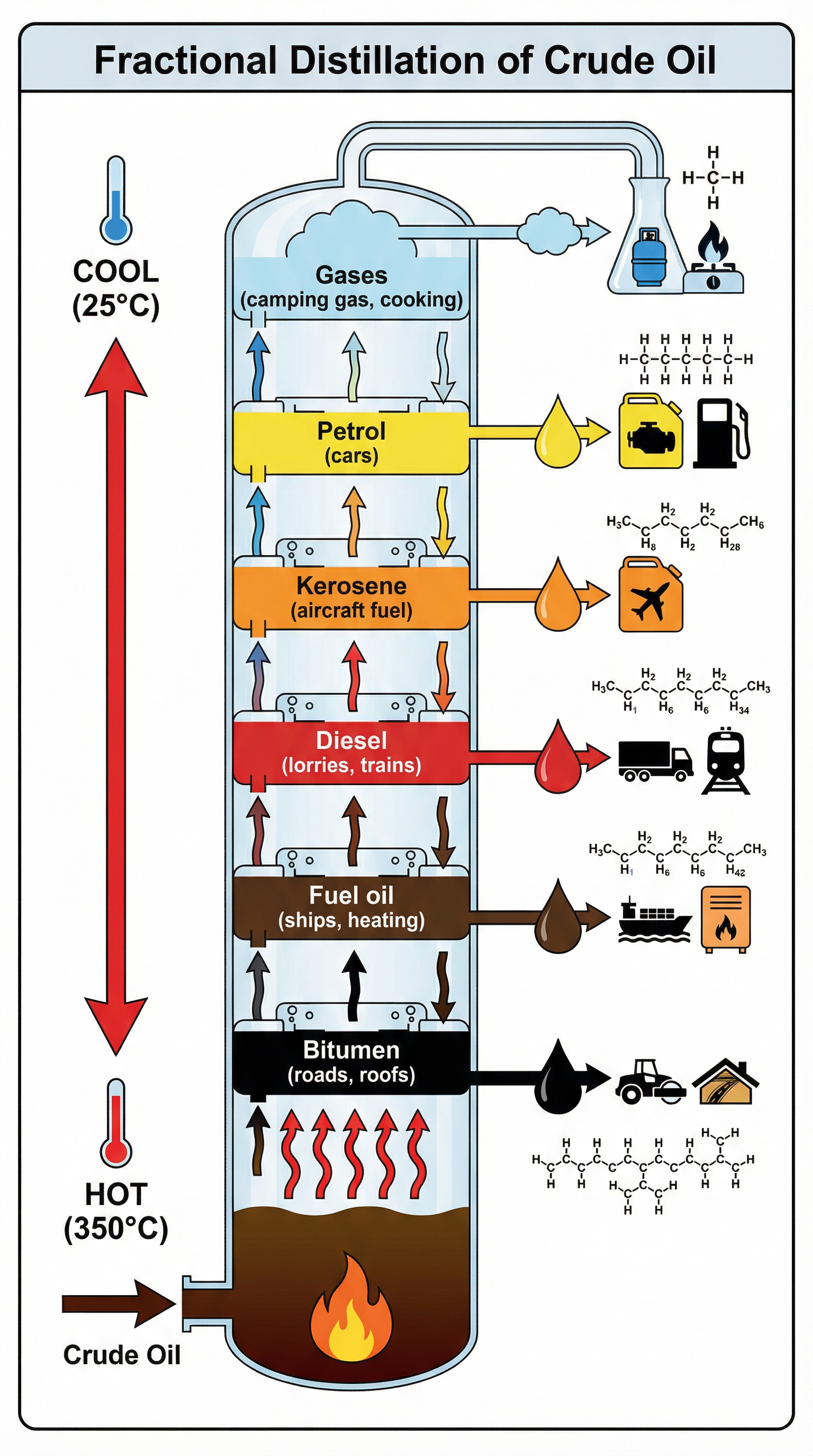

This is the industrial process used to separate crude oil into fractions. Candidates must be able to describe the process in detail. Crude oil is heated in a furnace to a high temperature (around 350°C), causing most of the hydrocarbons to vaporize. This hot liquid and vapor mixture is then pumped into the bottom of a fractionating column.

The column has a distinct temperature gradient: it is very hot at the bottom and gradually gets cooler towards the top. As the hot hydrocarbon vapors rise, they cool and condense at different levels where the temperature is equal to their boiling point. Each level has trays to collect the liquid fractions. Hydrocarbons with high boiling points condense at the bottom, while those with low boiling points continue to rise to the top.

Concept 3: Properties of Hydrocarbons

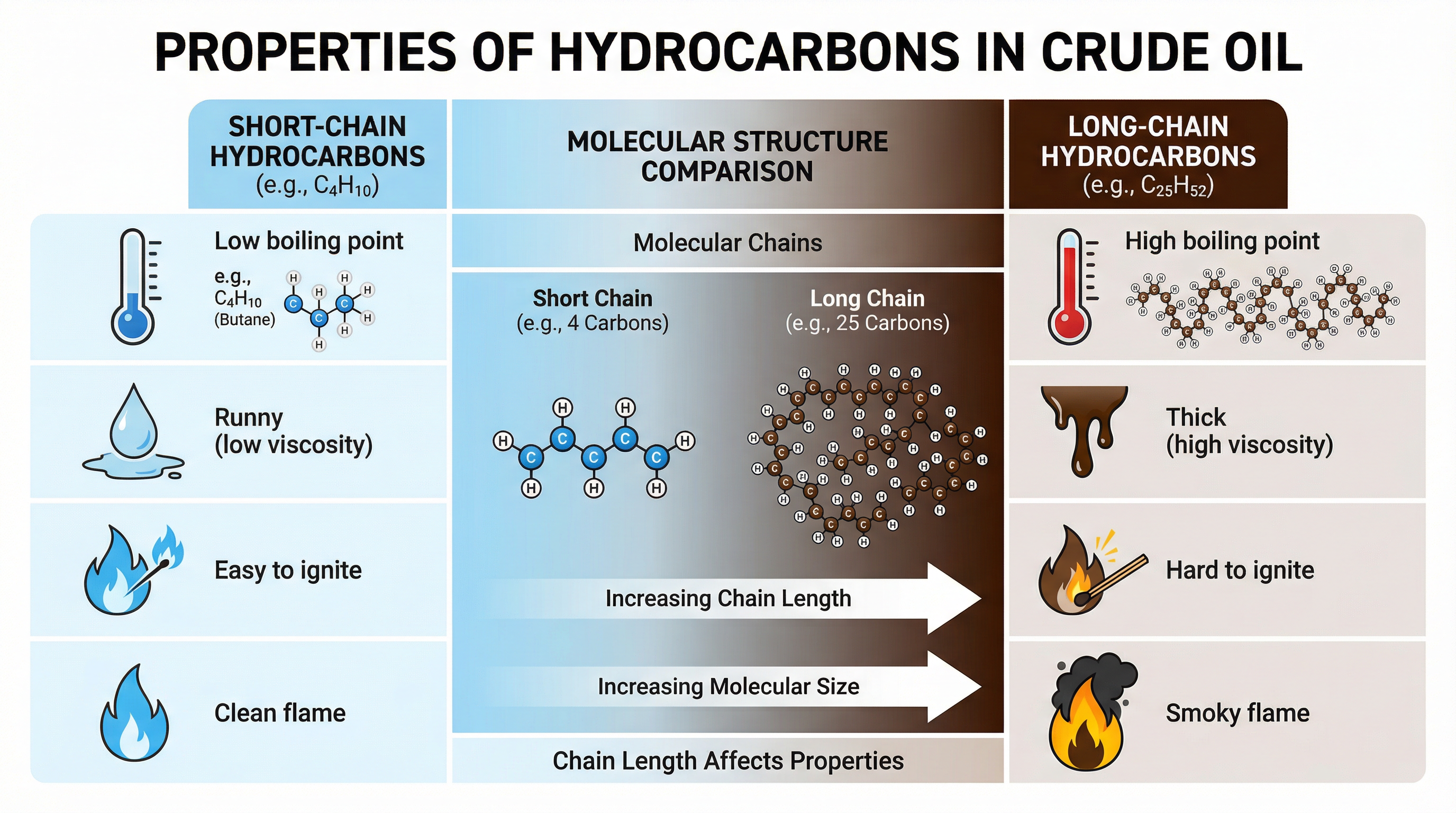

The properties of each fraction are determined by the size of the hydrocarbon molecules within it. There is a clear and predictable trend that you must learn:

- Short-chain hydrocarbons: Found at the top of the column (e.g., gases, petrol). They have low boiling points, are highly volatile, have low viscosity (they are runny), and are highly flammable.

- Long-chain hydrocarbons: Found at the bottom of the column (e.g., fuel oil, bitumen). They have high boiling points, are not very volatile, have high viscosity (they are thick and gloopy), and are not easily ignited.

The reason for these trends is intermolecular forces. Longer chains have more surface area and more points of contact, leading to stronger intermolecular forces between molecules. More energy is required to overcome these stronger forces, which results in a higher boiling point. This is a classic higher-tier explanation that secures top marks.

Mathematical/Scientific Relationships

The General Formula for Alkanes

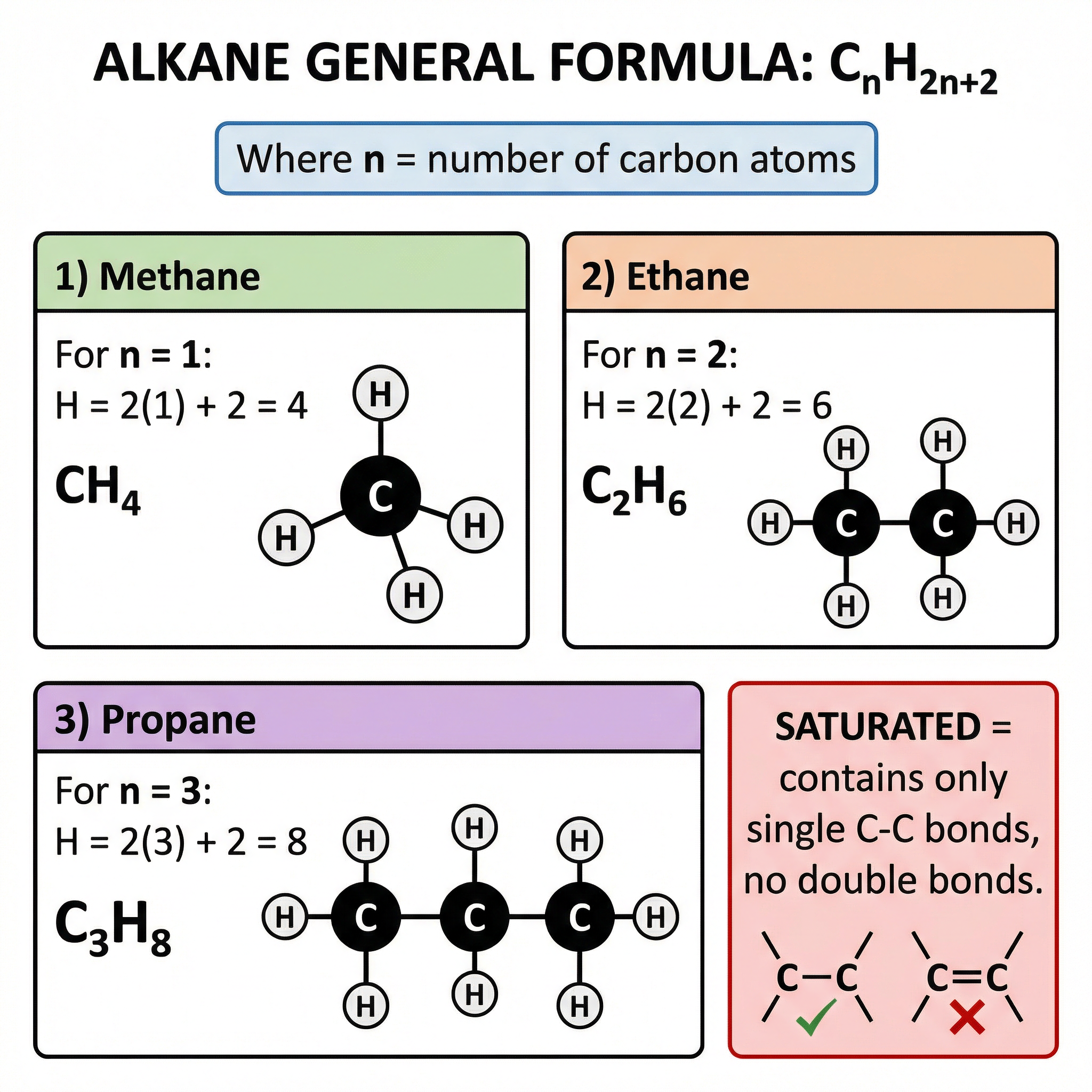

Alkanes are the primary type of hydrocarbon in crude oil. They are described as saturated because they only contain single carbon-carbon bonds. You must memorize their general formula:

C_n H_{2n+2}

- C represents a carbon atom.

- H represents a hydrogen atom.

- n is the number of carbon atoms in the molecule.

This formula is not given on the formula sheet, so it must be memorized. It allows you to work out the molecular formula of any alkane if you know the number of carbon atoms.

Example: A molecule of hexane has 6 carbon atoms (n=6). Using the formula, the number of hydrogen atoms will be (2 * 6) + 2 = 14. So, the molecular formula for hexane is C_6H_14.

Practical Applications

The fractions from crude oil are incredibly important and have a wide range of uses. Examiners expect you to know the main fractions and at least one use for each. This is a common source of 1 or 2-mark questions.

| Fraction | Approx. Chain Length | Boiling Range (°C) | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refinery Gases | C1 - C4 | < 25 | LPG for domestic heating and cooking |

| Gasoline (Petrol) | C5 - C12 | 40 - 75 | Fuel for cars |

| Kerosene | C11 - C16 | 160 - 250 | Fuel for jet engines, paraffin for lamps |

| Diesel (Gas Oil) | C15 - C18 | 250 - 350 | Fuel for lorries, buses, and trains |

| Fuel Oil | C20 - C50 | 350 - 400 | Fuel for ships, power stations, heating |

| Bitumen | > C70 | > 400 | Surfacing roads, roofing |

Podcast Script

"GCSE CHEMISTRY PODCAST: CRUDE OIL COMPOSITION

Duration: 10 minutes

Speaker: Female educator (warm, engaging, confident tone)

[INTRO - 1 minute]

Hello and welcome to this GCSE Chemistry revision podcast on Crude Oil Composition. I'm here to help you master Topic 2.7 from the Edexcel specification, and trust me, this is one of those topics that comes up year after year in the exams, so it's definitely worth your time.

Today, we're going to explore what crude oil actually is, how we separate it into useful fractions through fractional distillation, and why different hydrocarbons behave so differently. By the end of this podcast, you'll understand exactly what examiners are looking for when they ask about crude oil, and you'll have some brilliant memory tricks to help you remember the key facts.

So, let's dive in.

[CORE CONCEPTS - 5 minutes]

First things first: what is crude oil? In your exam, you need to define it as a finite resource and a complex mixture of hydrocarbons. That word "finite" is important because it means crude oil will eventually run out, it's not renewable. And when we say "mixture," we mean it contains many different compounds that aren't chemically bonded together. This is crucial because it means we can separate them using physical methods, not chemical reactions.

Now, crude oil on its own isn't particularly useful. We need to separate it into different fractions, and we do this using fractional distillation. Picture a tall tower, called a fractionating column. This column has a temperature gradient, and this is absolutely key: it's hottest at the bottom, around 350 degrees Celsius, and coolest at the top, around 25 degrees Celsius. Many students get this backwards in exams, so remember: hot at the bottom, cool at the top.

Here's how it works. Crude oil is heated until it vaporizes, and these hot vapors enter the column at the bottom. As the vapors rise up the column, they cool down. Each hydrocarbon has a different boiling point, so as the vapors cool, different hydrocarbons condense at different heights. When a vapor reaches a level where the temperature is below its boiling point, it condenses back into a liquid and is collected. That's your fraction.

Let me give you the six main fractions in order from top to bottom, and I want you to memorize this sequence because it's exam gold. At the top, we collect gases, used for camping gas and cooking. Then petrol, which fuels cars. Next is kerosene, that's aircraft fuel. Below that is diesel for lorries and trains. Then fuel oil for ships and heating. And finally, at the very bottom, we get bitumen, which is used for roads and roofs. A great mnemonic for this is "Good Penguins Keep Diving For Biscuits." Gases, Petrol, Kerosene, Diesel, Fuel oil, Bitumen.

Now, why do different hydrocarbons condense at different heights? It all comes down to their molecular structure. Hydrocarbons in crude oil are mostly alkanes, and alkanes have the general formula C-n-H-2n-plus-2, where n is the number of carbon atoms. This formula tells you that alkanes are saturated, meaning they only have single carbon-carbon bonds, no double bonds.

Short-chain hydrocarbons, like methane or butane with just a few carbon atoms, have low boiling points. They're runny, easy to ignite, and burn with a clean flame. Long-chain hydrocarbons, like those with 20 or 30 carbon atoms, have high boiling points. They're thick and viscous, hard to ignite, and burn with a smoky flame.

The reason for this difference is intermolecular forces. Longer molecules have stronger intermolecular forces between them, so you need more energy to overcome these forces and turn the liquid into a gas. That's why long-chain hydrocarbons have higher boiling points and condense lower down in the column where it's hotter.

Here's a critical exam point: during fractional distillation, no covalent bonds are broken. We're only overcoming intermolecular forces. If a question asks you to explain the process, make sure you say "intermolecular forces are overcome," not "bonds are broken." That's a mark lost if you get it wrong.

[EXAM TIPS & COMMON MISTAKES - 2 minutes]

Let's talk about how to maximize your marks on this topic. Edexcel loves to test your understanding of the temperature gradient. If you're asked to describe the fractionating column, you must state that it's hotter at the bottom and cooler at the top. Don't assume the examiner knows you know this, write it down.

Another common mistake is confusing fractional distillation with cracking. Fractional distillation is a physical separation process, no chemical reactions occur. Cracking, which you'll study separately, is a chemical process that breaks long-chain hydrocarbons into shorter ones. Keep these distinct in your mind.

When defining "saturated," make sure you're talking about organic chemistry, not solutions. A saturated hydrocarbon means it contains only single carbon-carbon bonds, no double bonds. Students often write about solutions where no more solute can dissolve, but that's not what saturated means in this context.

And here's a top tip: if you're given a molecular formula and asked if it's an alkane, use the general formula C-n-H-2n-plus-2 to check. For example, if you're given C-5-H-12, substitute n equals 5 into the formula: 2 times 5 plus 2 equals 12. Yes, it's an alkane. This is a quick way to verify your answer and pick up easy marks.

Finally, know your fractions and their uses. Examiners love to test whether you can match kerosene to aircraft fuel or diesel to trains and lorries. Make sure you've memorized these.

[QUICK-FIRE RECALL QUIZ - 1 minute]

Right, let's test your recall with some quick-fire questions. I'll give you a moment to think of the answer after each one.

Question 1: What is the general formula for alkanes? The answer is C-n-H-2n-plus-2.

Question 2: Is the fractionating column hotter at the top or the bottom? The answer is hotter at the bottom.

Question 3: What does "saturated" mean for a hydrocarbon? It means it contains only single carbon-carbon bonds, no double bonds.

Question 4: Which fraction is used as aircraft fuel? The answer is kerosene.

Question 5: During fractional distillation, do covalent bonds break? No, only intermolecular forces are overcome.

How did you do? If you got them all right, brilliant. If not, go back and review those sections.

[SUMMARY & SIGN-OFF - 1 minute]

Okay, let's wrap up. Crude oil is a finite resource and a complex mixture of hydrocarbons, mostly alkanes. We separate it using fractional distillation in a column that's hot at the bottom and cool at the top. Different fractions condense at different heights based on their boiling points, which depend on the strength of intermolecular forces. Short chains have low boiling points and are runny, while long chains have high boiling points and are viscous.

Remember your mnemonic: Good Penguins Keep Diving For Biscuits. And always use the general formula C-n-H-2n-plus-2 to check if a molecule is an alkane.

This topic is worth around 5 to 8 marks in your exam, and with the knowledge you've gained today, you're well-prepared to earn every single one of them.

Thanks for listening, and good luck with your revision. You've got this!