Study Notes

Overview

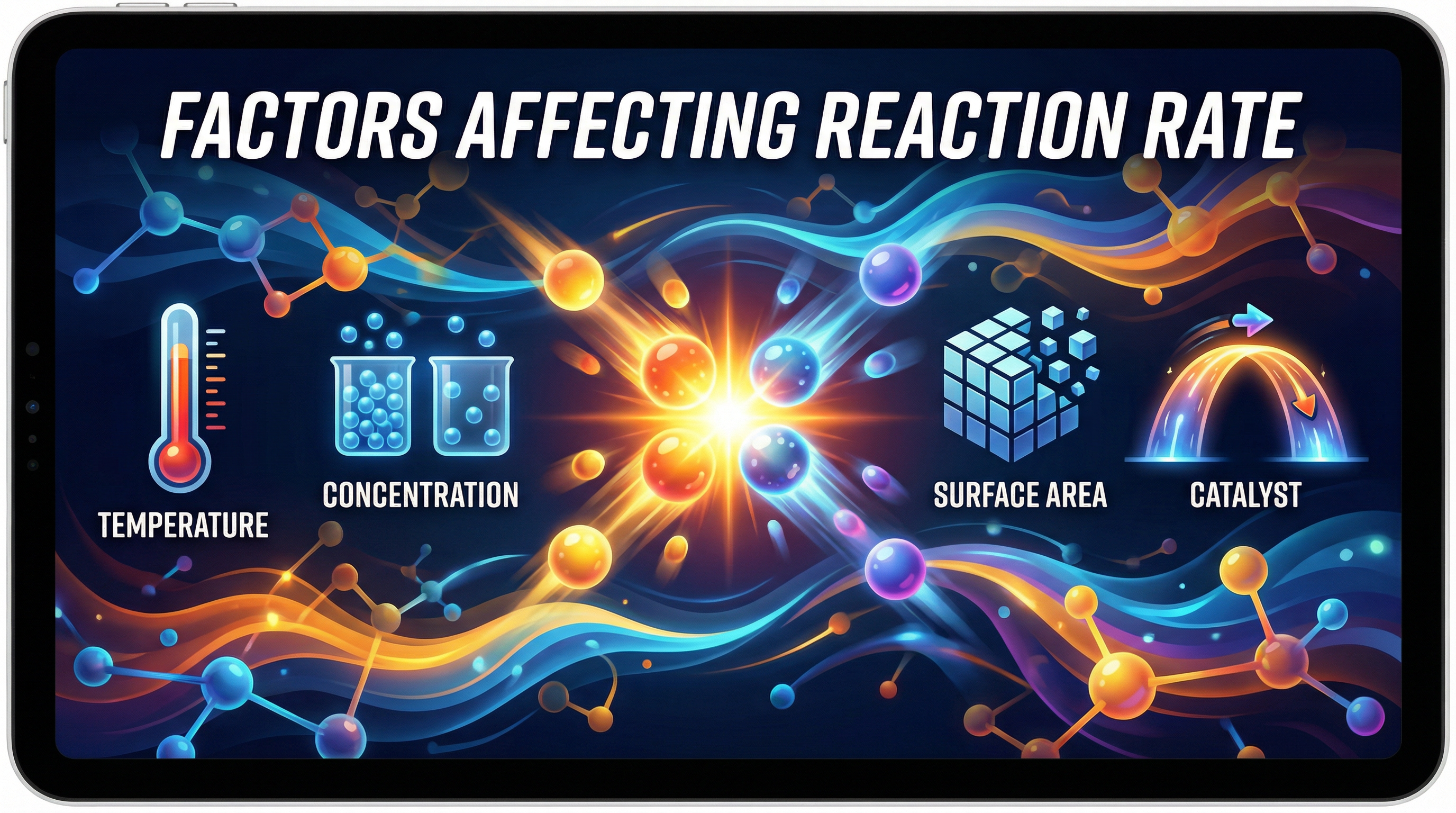

Factors Affecting Reaction Rate is a cornerstone topic in GCSE Chemistry that bridges theoretical understanding with practical application. This topic examines why some reactions occur rapidly while others proceed slowly, and crucially, how we can control reaction rates in industrial and laboratory settings. Understanding collision theory—the idea that particles must collide with sufficient energy and correct orientation—is fundamental to explaining all four factors: temperature, concentration, surface area, and catalysts. Edexcel examiners favor this topic because it allows them to assess your ability to explain particle-level processes, design valid experiments with appropriate controls, and analyze rate graphs mathematically using tangents. Typical exam questions range from 2-mark definitions to 6-mark extended response questions requiring you to plan investigations or explain multiple factors. This topic also connects synoptically to energetics, equilibrium, and industrial chemistry, making it a high-value area for revision.

Key Concepts

Concept 1: Collision Theory

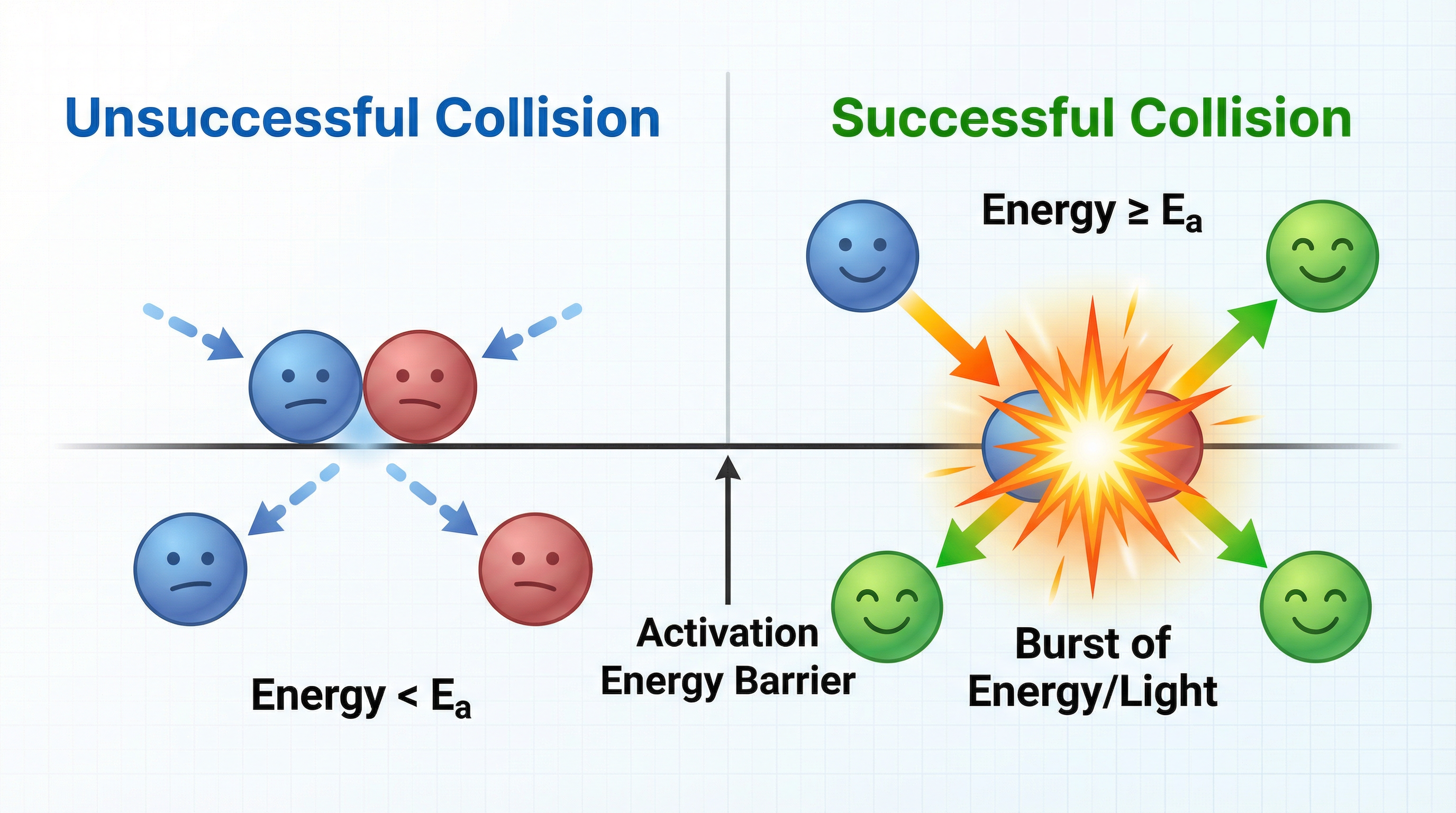

Collision theory is the foundation for understanding reaction rates. For a chemical reaction to occur, reactant particles must collide. However, not every collision results in a reaction—only successful collisions do. A successful collision requires two conditions: first, the particles must possess energy equal to or greater than the activation energy (Ea), which is the minimum energy needed to break bonds in the reactants; second, the particles must collide with the correct orientation so that reactive parts of the molecules come into contact. Think of activation energy as an energy barrier that must be overcome. If particles collide with insufficient energy or at the wrong angle, they simply bounce apart unchanged. The rate of reaction depends on both the frequency of collisions and the proportion of those collisions that are successful. This distinction is crucial for explaining why different factors affect rate in different ways.

Example: In the reaction between hydrochloric acid and marble chips (calcium carbonate), acid particles must collide with carbonate ions on the surface of the marble with enough energy to break the ionic bonds in CaCO₃. If the collision energy is below the activation energy, the particles rebound without reacting, even though they made contact.

Concept 2: Effect of Temperature

Temperature has the most significant effect on reaction rate, and explaining it fully is worth multiple marks in exams. When temperature increases, particles gain kinetic energy and move faster. This has two consequences. First, faster-moving particles collide more frequently per unit time, increasing the collision frequency. Second, and more importantly, a greater proportion of particles now possess energy equal to or greater than the activation energy. This means more collisions are successful. While both effects contribute to the increased rate, the second effect—the increased proportion of successful collisions—is the dominant factor. Examiners specifically look for candidates to mention both the increased frequency and the increased proportion of successful collisions. Stating only that "particles move faster" will earn partial credit but not full marks.

Example: Heating a mixture of sodium thiosulfate and hydrochloric acid from 20°C to 40°C might double or even triple the reaction rate. This dramatic increase occurs primarily because many more particles now exceed the activation energy threshold, not just because they're colliding more often.

Concept 3: Effect of Concentration and Pressure

Increasing the concentration of a solution, or the pressure of a gas, increases the number of particles in a given volume. With more particles present, there are more opportunities for collisions per unit time—the collision frequency increases. Crucially, concentration and pressure do not affect the energy of individual particles, so they do not change the proportion of successful collisions. They simply increase how often particles collide. This is a common source of error: candidates sometimes incorrectly state that increasing concentration increases the "energy" of collisions. It does not—it only increases their frequency. For gases, increasing pressure has the same effect as increasing concentration because you're compressing more particles into the same space.

Example: Doubling the concentration of hydrochloric acid from 1.0 mol/dm³ to 2.0 mol/dm³ doubles the number of acid particles in the same volume, so acid particles collide with marble chips twice as often, doubling the initial rate of reaction.

Concept 4: Effect of Surface Area

Surface area applies to reactions involving solids. Only particles on the surface of a solid are available to collide with particles in a surrounding liquid or gas. If you break a solid into smaller pieces, you increase the total surface area exposed to reactants. More surface area means more particles are available for collision at any given moment, increasing the collision frequency and therefore the rate. This is why powdered reactants react much faster than large lumps of the same mass. In practical terms, this is why industrial processes often use finely divided catalysts or powdered reactants to maximize reaction rates.

Example: A single large marble chip might have a surface area of 2 cm², but if you crush it into powder, the total surface area might increase to 200 cm² or more. This hundred-fold increase in surface area leads to a dramatic increase in reaction rate with acid, as many more carbonate ions are now accessible to acid particles.

Concept 5: Catalysts

A catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction without being chemically changed or used up by the reaction. Catalysts work by providing an alternative reaction pathway with a lower activation energy. By lowering Ea, a catalyst allows a greater proportion of collisions to be successful, even though the particles' energy distribution remains unchanged. Importantly, a catalyst does not provide energy to the reaction—it is not a fuel or reactant. It simply makes it easier for particles to overcome the energy barrier. Catalysts are crucial in industry because they allow reactions to proceed at useful rates without requiring high temperatures, saving energy and costs. Different reactions require different catalysts; for example, iron is used in the Haber process, while manganese(IV) oxide catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide.

Example: The decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (2H₂O₂ → 2H₂O + O₂) is very slow at room temperature. Adding a small amount of manganese(IV) oxide (MnO₂) dramatically increases the rate by providing a lower-energy pathway. The MnO₂ can be recovered unchanged at the end, demonstrating that it is not consumed.

Mathematical and Scientific Relationships

Rate of Reaction

Rate of reaction is defined as the change in concentration (or amount) of a reactant or product per unit time. It is typically measured in units such as cm³/s (for gas volume), g/s (for mass change), or mol/dm³/s (for concentration change). The general formula is:

Rate = Change in quantity / Time takenFor example, if 50 cm³ of gas is produced in 10 seconds, the mean rate is 50 ÷ 10 = 5 cm³/s.

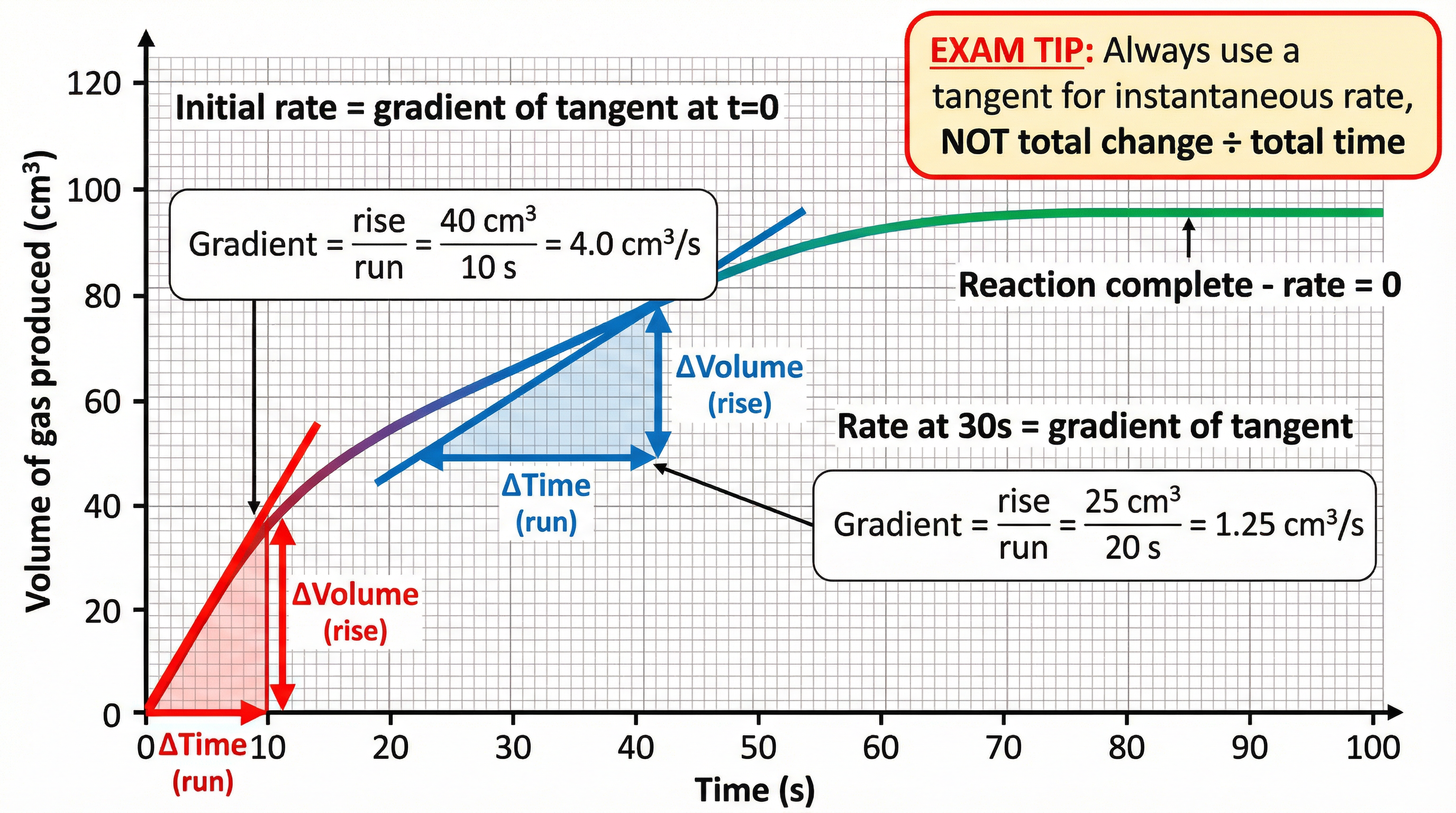

Instantaneous Rate from Graphs

When analyzing a rate graph (e.g., volume of gas produced vs. time), the instantaneous rate at any point is found by drawing a tangent to the curve at that point and calculating its gradient:

Gradient = Rise / Run = Δy / ΔxFor example, if a tangent at t = 30s rises by 25 cm³ over a horizontal distance of 20 s, the rate at 30s is 25 ÷ 20 = 1.25 cm³/s. Always include units in your final answer. The steeper the gradient, the faster the rate. At the start of a reaction, the curve is steepest (highest rate), and as the reaction proceeds, the curve levels off (rate decreases) until it becomes horizontal (rate = 0, reaction complete).

Inverse Relationship: Time and Rate

There is an inverse relationship between the time taken for a reaction to complete and the rate of reaction:

Rate ∝ 1 / TimeIf a reaction takes half the time, the rate has doubled. This relationship is often tested when candidates measure the time for a cross to disappear in the sodium thiosulfate reaction. A shorter time indicates a faster rate, not a slower one.

Practical Applications

Required Practical: Investigating Reaction Rates

Edexcel includes a required practical where candidates investigate how changing concentration, temperature, or surface area affects the rate of a reaction. A common setup involves reacting marble chips (calcium carbonate) with hydrochloric acid and measuring the volume of carbon dioxide gas produced over time using a gas syringe or measuring cylinder over water.

Apparatus: Conical flask, marble chips, hydrochloric acid, gas syringe or inverted measuring cylinder, stopwatch, balance (for mass loss method), water bath (for temperature investigations).

Method (investigating effect of concentration):

- Measure 50 cm³ of 1.0 mol/dm³ HCl into a conical flask.

- Add 5 g of marble chips and immediately start the stopwatch.

- Record the volume of gas produced every 10 seconds until the reaction stops.

- Repeat with 0.75 mol/dm³, 0.5 mol/dm³, and 0.25 mol/dm³ HCl, keeping all other variables constant.

- Plot graphs of volume vs. time and draw tangents to calculate initial rates.

Control Variables: Volume of acid (50 cm³), mass of marble chips (5 g), size of marble chips (use same batch), temperature (use water bath if necessary).

Expected Results: Higher concentration produces steeper initial gradients (faster initial rate) and the same final volume of gas (if acid is in excess) or different final volumes (if marble is in excess).

Common Errors: Not controlling temperature, using different-sized marble chips, not starting the stopwatch immediately, incorrectly calculating rate by using total change ÷ total time instead of tangent gradient.

How Examiners Test It: You may be asked to plan an investigation (6 marks), identify control variables (2-3 marks), draw or interpret rate graphs (3-4 marks), or calculate rates from data (2-3 marks).

Industrial Applications

Understanding reaction rates is vital in industry. The Haber process for ammonia production uses high temperature (450°C) and an iron catalyst to achieve economically viable rates. Contact process for sulfuric acid uses vanadium(V) oxide as a catalyst. Catalytic converters in cars use platinum and rhodium to speed up the conversion of harmful exhaust gases. In all cases, controlling rate factors maximizes efficiency and profitability while minimizing energy costs.

Listen to the Podcast

Listen to this 10-minute educational podcast for a comprehensive audio review of all key concepts, exam tips, and a quick-fire recall quiz to test your understanding.