Study Notes

Overview

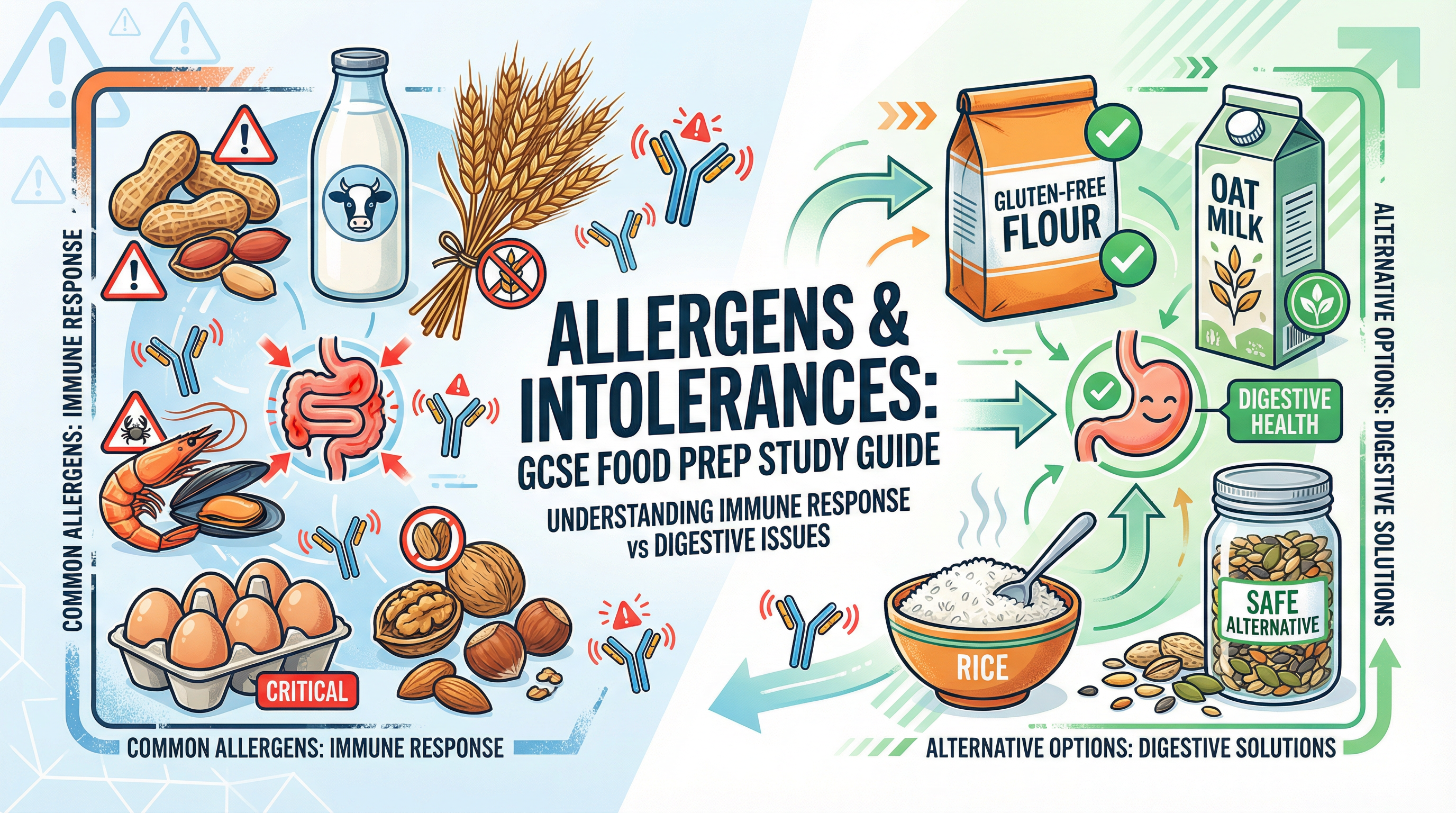

This topic explores the critical differences between food allergies and food intolerances, a core component of the AQA GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition specification. Examiners expect candidates to demonstrate a clear understanding of the distinct biological mechanisms: the immune response in allergies (specifically involving IgE antibodies) versus the enzymatic deficiencies in intolerances. Mastery of the 14 major allergens mandated by UK law is essential, as is the ability to analyse and mitigate risks of cross-contamination in both domestic and commercial kitchens. Furthermore, a significant portion of marks are awarded for the ability to justify the selection of alternative ingredients based on their functional properties when modifying recipes for specific dietary needs. This guide will provide the detailed knowledge and exam technique required to excel in questions related to this topic.

Key Concepts

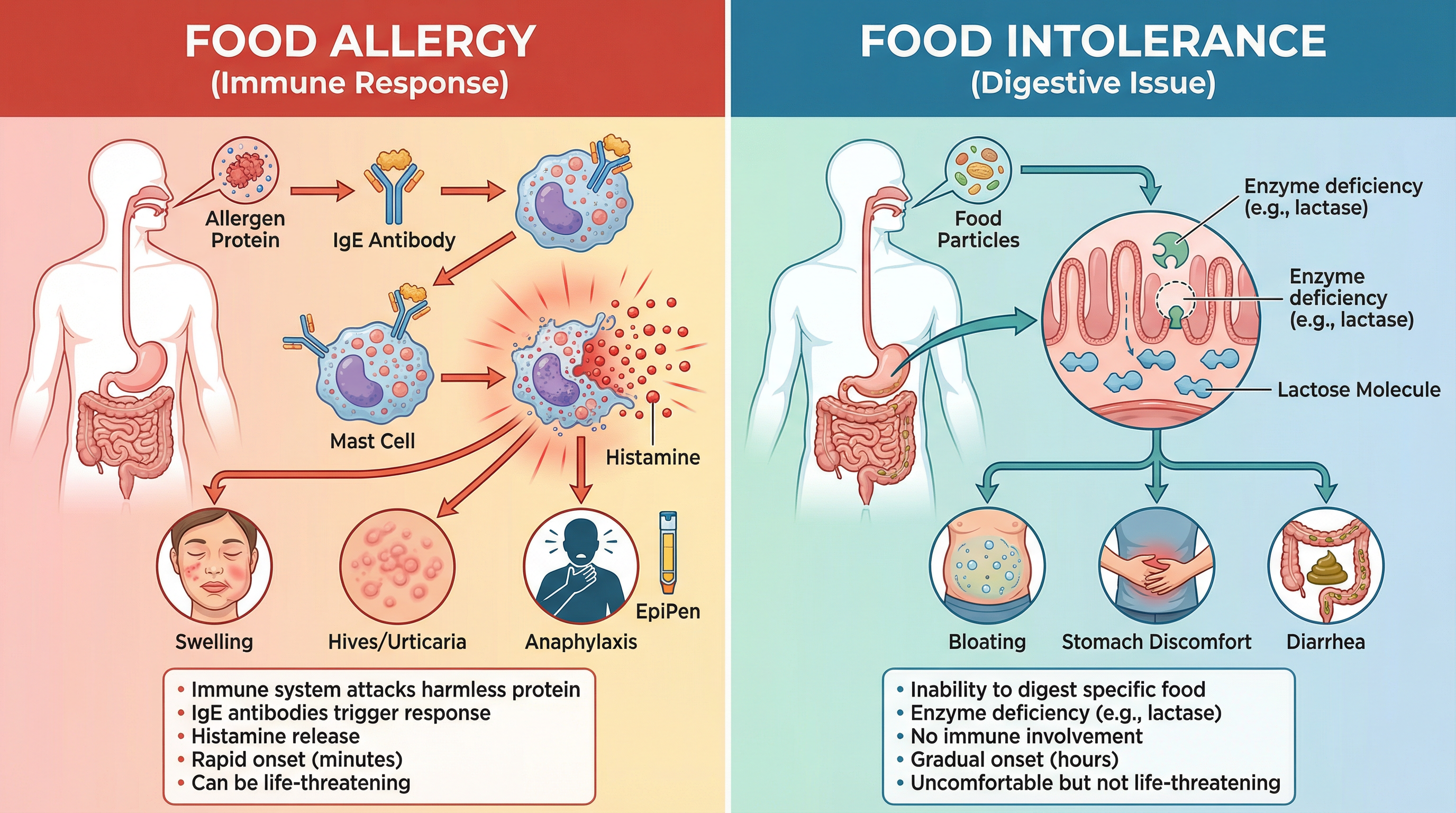

Food Allergy: The Immune System Response

What happens: A food allergy is a rapid and potentially life-threatening reaction caused by the immune system. The body mistakenly identifies a protein in a food (an allergen) as a threat and produces Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies. These antibodies attach to mast cells, which, upon subsequent exposure to the allergen, release large amounts of chemicals, including histamine. This chemical release causes allergic symptoms.

Why it matters: For the exam, candidates must use precise terminology. Credit is given for mentioning IgE antibodies, mast cells, and histamine release. The onset is rapid (minutes) and can be triggered by even a trace amount of the allergen. Symptoms range from mild (urticaria/hives, itching, swelling) to severe (anaphylaxis), which can be fatal.

Food Intolerance: A Digestive Issue

What happens: A food intolerance is a non-immune system response. It occurs when the body is unable to properly digest a certain food, often due to a lack of a specific enzyme. The most common example is lactose intolerance, where the body lacks the enzyme lactase to break down lactose (the sugar in milk). This leads to digestive discomfort as the undigested food ferments in the gut.

Why it matters: Candidates must clearly differentiate this from an allergy. Key marking points include mentioning enzyme deficiency, the digestive system (not immune), and the slower onset of symptoms (hours). Symptoms are generally less severe and may include bloating, gas, and diarrhoea. Individuals can often tolerate small amounts of the food without a reaction.

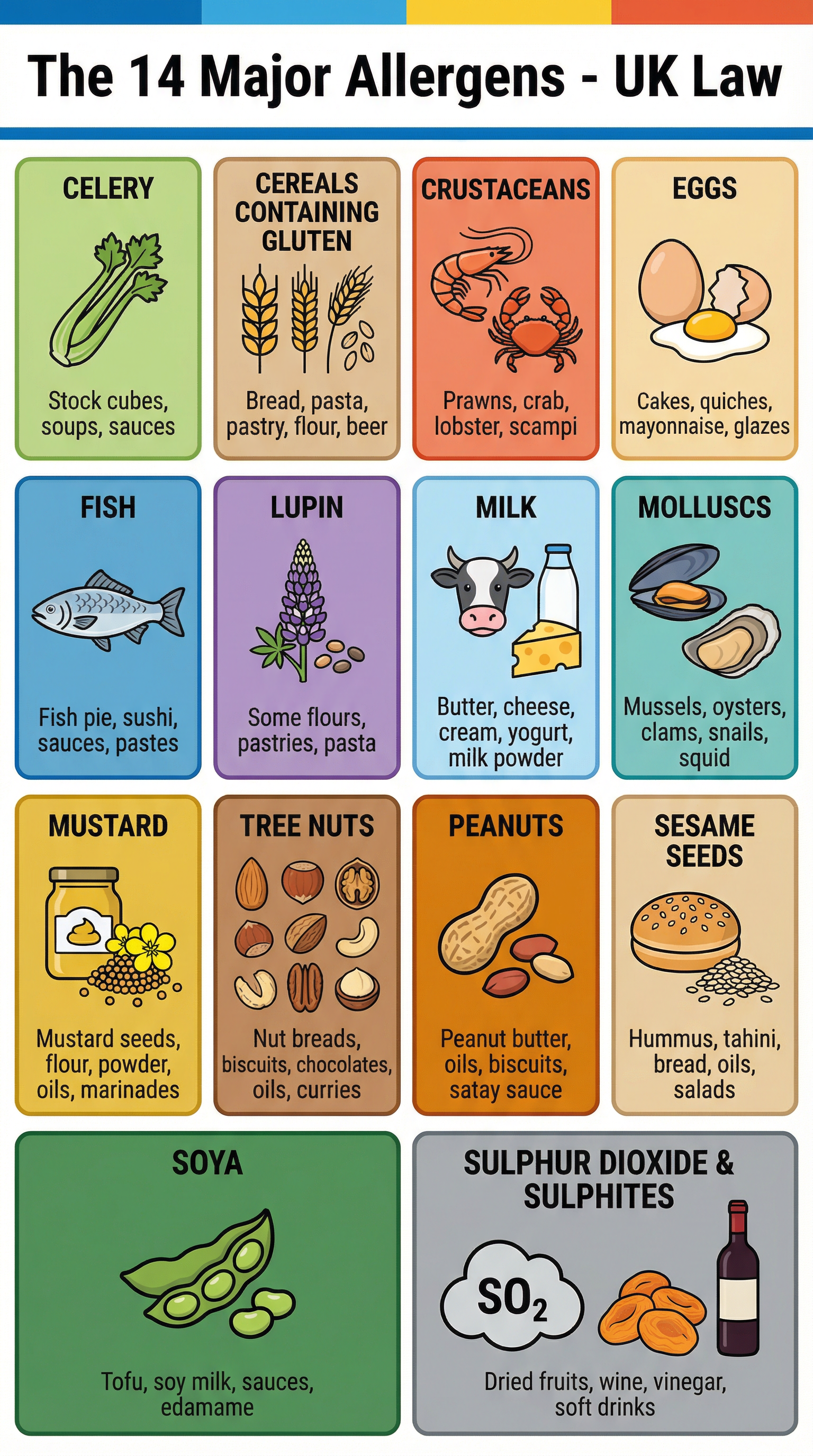

The 14 Major Allergens

What they are: UK and EU law requires that 14 specific allergens are clearly declared on food labels and menus. Candidates are expected to be able to list these.

Why it matters: Marks are awarded for naming the specific allergens, not broad categories. For example, candidates should write 'milk' not 'dairy', and distinguish between 'peanuts' and 'tree nuts'.

Cross-Contamination

What it is: The unintentional transfer of allergens from one food to another. This can happen directly (e.g., a knife used to cut a nut-containing cake is then used on a plain cake) or indirectly (e.g., airborne flour particles settling on a gluten-free dish).

Why it matters: In exam questions, candidates must identify specific cross-contamination risks in a given scenario (e.g., a busy kitchen) and propose practical control measures. Examples include using separate colour-coded chopping boards, dedicated fryers, and storing allergen-containing ingredients separately.

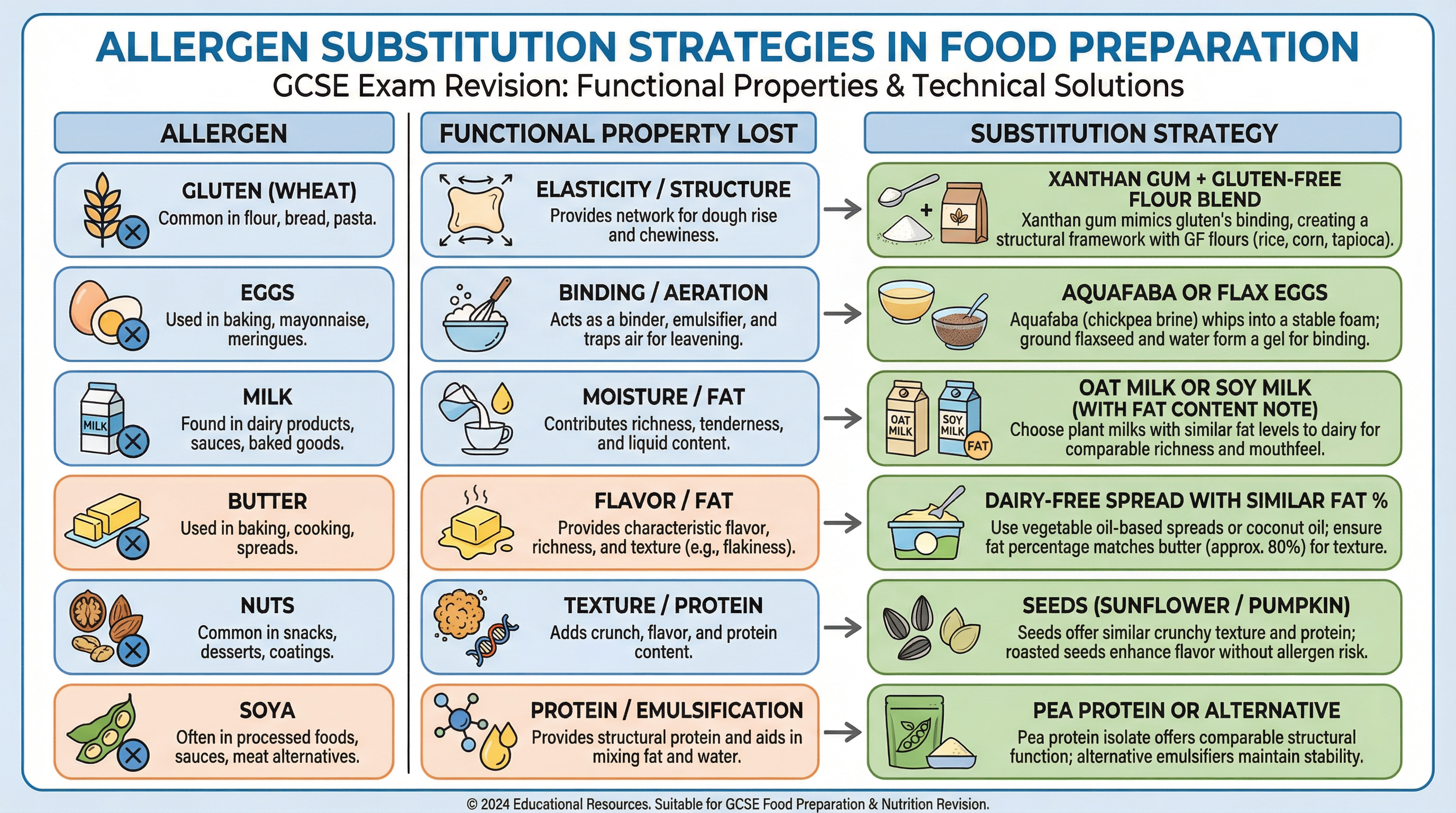

Functional Properties & Substitution

What it is: When removing an allergen from a recipe, its function must be replaced. For example, gluten in flour provides structure and elasticity; eggs can be used for binding, aeration, or emulsification.

Why it matters: High-level answers will not just suggest a substitute, but will explain why it works. Candidates must demonstrate an understanding of the functional properties of ingredients and how to replicate them with alternatives.