Study Notes

Overview

This study guide delves into the scientific principles underpinning cooking methods, a cornerstone of the Edexcel GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition specification. Examiners expect candidates to demonstrate a clear understanding of how heat is transferred to food and the subsequent physicochemical changes that occur. A high-scoring answer moves beyond descriptive accounts of cooking, instead providing a robust scientific explanation. You will be expected to link the three methods of heat transfer—conduction, convection, and radiation—to specific cooking techniques and explain their impact on ingredients. Furthermore, you must be able to articulate how these processes alter the nutritional value, texture, and flavour of food, using precise terminology such as denaturation, coagulation, gelatinisation, and the Maillard reaction. This guide will equip you with the detailed knowledge and analytical framework required to explain not just how to cook, but why specific methods are chosen to achieve desired outcomes.

The Science of Heat Transfer

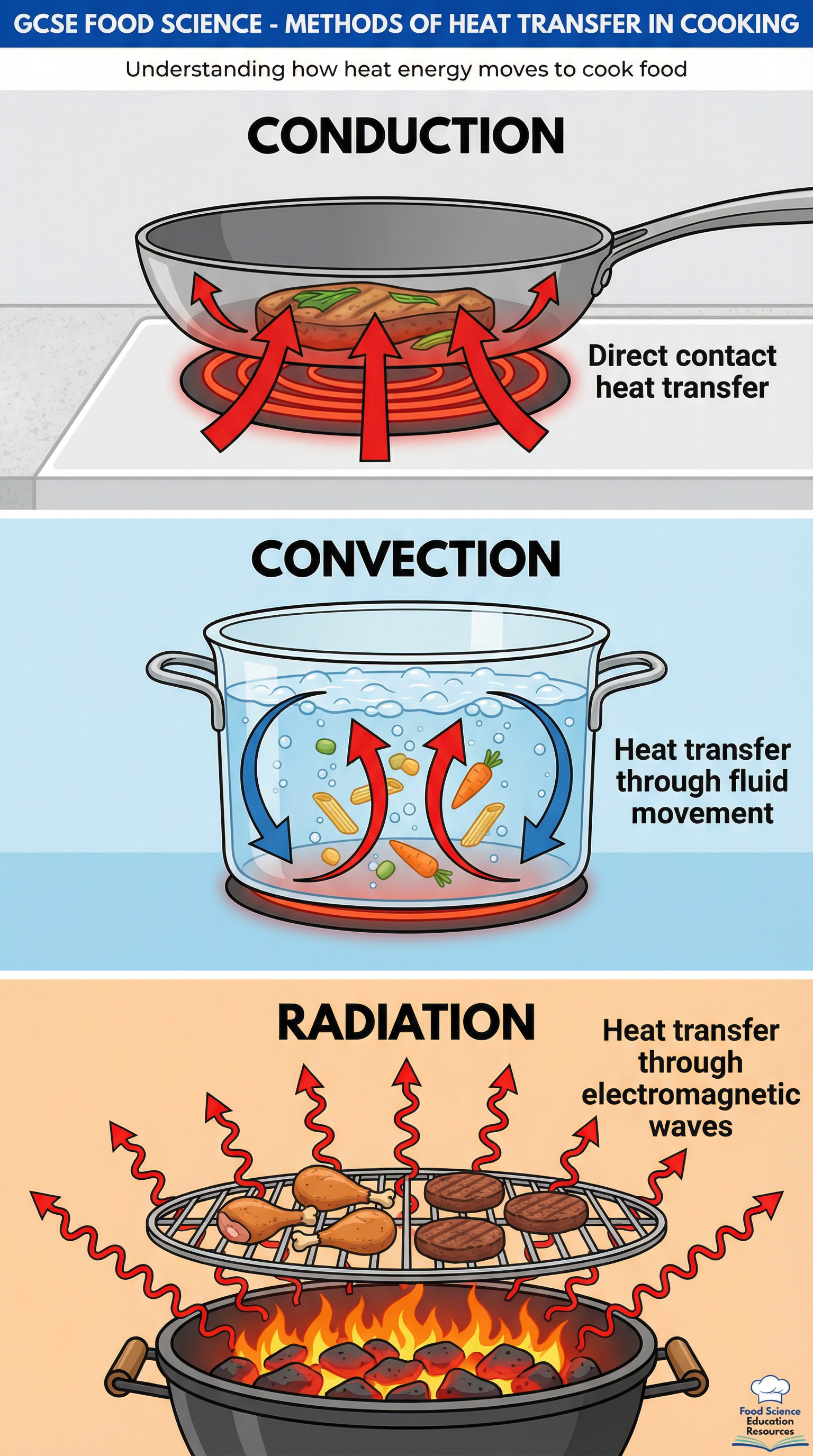

Understanding how heat energy moves is critical. All cooking methods rely on one or more of these three transfer mechanisms. Credit is awarded for identifying the primary method of heat transfer for a given cooking process.

Conduction

What it is: The transfer of heat through direct contact. Heat energy excites molecules, which vibrate and pass the energy to adjacent molecules.

How it works: When a frying pan is placed on a hot hob, the metal heats up. When food is added to the pan, the heat is transferred directly from the pan to the surface of the food. Metals like copper and aluminium are excellent conductors, which is why they are used for cookware.

Exam Example: "In pan-frying, heat is transferred to the chicken breast via conduction from the hot surface of the pan."

Convection

What it is: The transfer of heat through the movement of fluids (liquids or gases). When a fluid is heated, it becomes less dense and rises. Cooler, denser fluid sinks to take its place, creating a circular flow called a convection current.

How it works: In a conventional oven, the air is heated by an element. This hot air circulates around the food, cooking it. In a pot of boiling water, convection currents ensure the water is evenly heated, cooking the food submerged within it.

Exam Example: "Baking a cake relies on convection currents, as the hot air circulates within the oven to cook the batter evenly."

Radiation

What it is: The transfer of heat via infrared electromagnetic waves. Unlike conduction and convection, it does not require a medium to travel through.

How it works: A grill or toaster uses a heating element that emits intense infrared radiation. These waves travel through the air and are absorbed by the surface of the food, causing it to heat up rapidly. This is why grilling is excellent for browning surfaces.

Exam Example: "Grilling a sausage cooks it primarily through radiation, where infrared waves from the heating element are absorbed by the meat's surface."

Key Chemical Changes in Food

Cooking is applied chemistry. You must be able to name and explain the key chemical changes that occur when proteins, carbohydrates, and fats are heated.

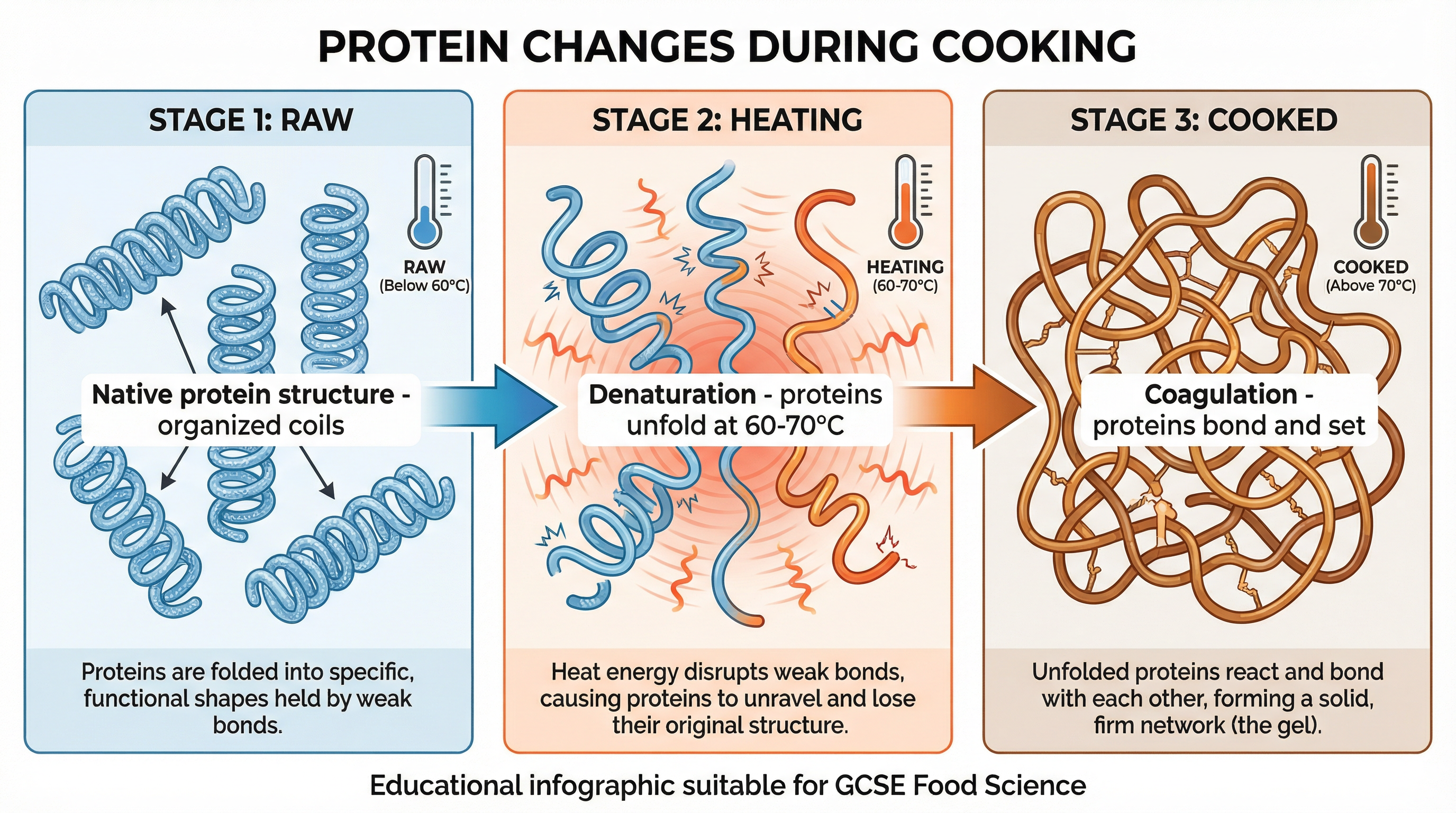

Protein: Denaturation & Coagulation

Proteins are long chains of amino acids, folded into complex, specific shapes. Heat disrupts these structures.

- Denaturation: This is the initial unfolding and uncoiling of the protein's natural structure. The weak bonds holding the protein in its shape are broken by heat energy (typically between 60-70°C). The protein changes from a complex 3D shape to a more linear chain. This change is irreversible.

- Coagulation: As heating continues, the denatured protein chains bond with each other, forming a solid, firm network. Water becomes trapped within this network. A clear example is a raw egg (liquid) turning solid and opaque upon cooking.

Exam Knowledge: Use these terms to describe changes in meat, fish, eggs, and dairy.

Carbohydrates: Gelatinisation, Dextrinisation & Caramelisation

Carbohydrates undergo several important changes when heated.

- Gelatinisation: This occurs when starch granules are heated in the presence of a liquid. The granules absorb the liquid, swell, and eventually rupture (at around 85°C), releasing starch molecules that thicken the liquid. This is the principle behind thickening sauces with flour or cornflour.

- Dextrinisation: This is the browning of starch when subjected to dry heat. The heat breaks down the long starch molecules into smaller, sweeter-tasting molecules called dextrins. This is responsible for the brown colour and crisp texture of toast and baked goods.

- Caramelisation: This is the breakdown of sugar by heat (at high temperatures, ~160°C+). The sugar melts and undergoes a series of chemical reactions, creating a range of brown-coloured, nutty, and bitter flavour compounds. It is distinct from the Maillard reaction as it involves only sugar, not protein.

Fats: Melting & Smoking

Fats simply melt when heated, changing from a solid to a liquid state. If heated to a very high temperature, fats will begin to break down, producing a blue smoke. This is known as the 'smoke point' and indicates the fat is degrading.

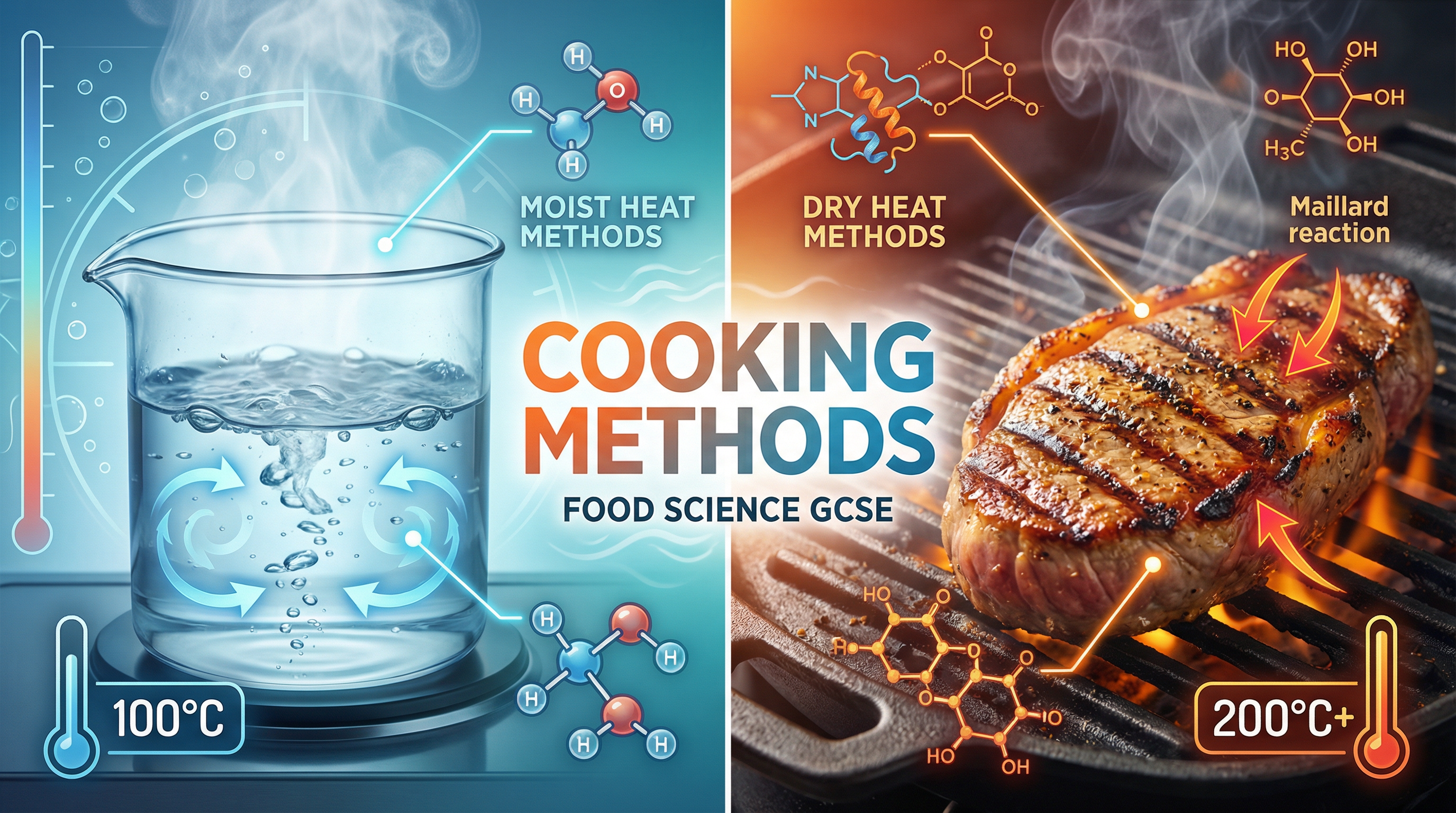

The Maillard Reaction: The Science of Browning

The Maillard reaction is one of the most important reactions in food chemistry and a favourite of examiners. It is a complex chemical reaction between amino acids (from proteins) and reducing sugars that occurs in the presence of dry heat. It is responsible for the characteristic brown colour and savoury flavour of many cooked foods, such as seared steak, baked bread, and roasted coffee.

Conditions Required: Dry heat (conduction or radiation), temperatures above 140°C.

Outcome: Development of a brown crust, complex aromas, and deep, savoury flavours.

Impact of Cooking on Nutritional Value

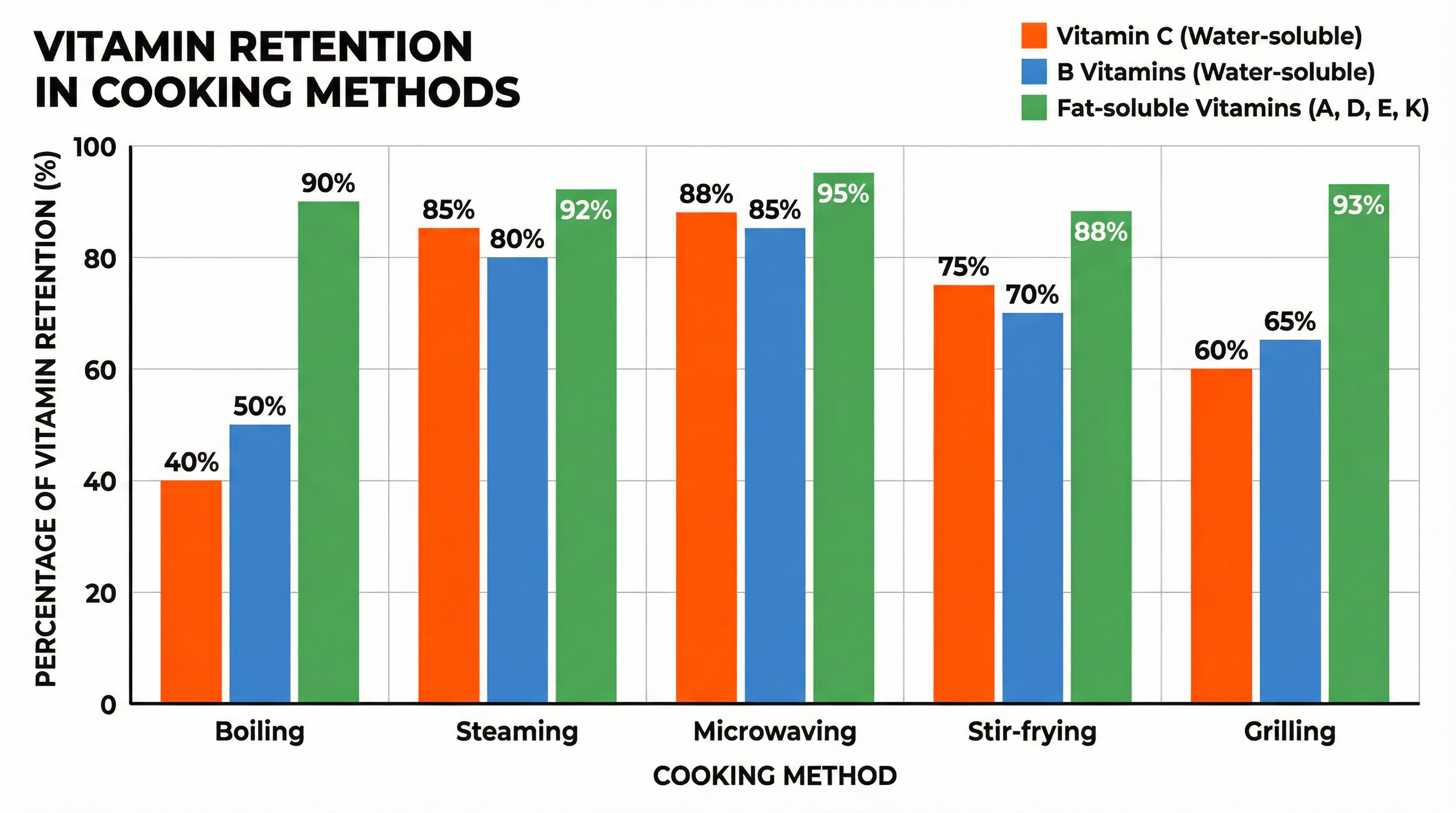

Cooking can both improve and diminish the nutritional content of food. A key area for exam questions is the effect of cooking on vitamins.

- Water-Soluble Vitamins (Vitamin C and B-Group): These are volatile and easily destroyed by heat and light. They also leach (dissolve) into cooking water. Boiling causes the highest loss of these vitamins. Methods like steaming, stir-frying, and microwaving, which use less water and shorter cooking times, result in much better retention.

- Fat-Soluble Vitamins (A, D, E, K): These are more stable to heat than water-soluble vitamins. They are not lost in cooking water but can be lost if the fat they are dissolved in is discarded.

- Minerals: Minerals are stable to heat but can be leached into cooking water during boiling.

Exam Tip: When asked to evaluate a cooking method, always consider its impact on water-soluble vitamins. Credit is given for suggesting methods that conserve nutritional value, such as steaming vegetables instead of boiling them.