Study Notes

Overview

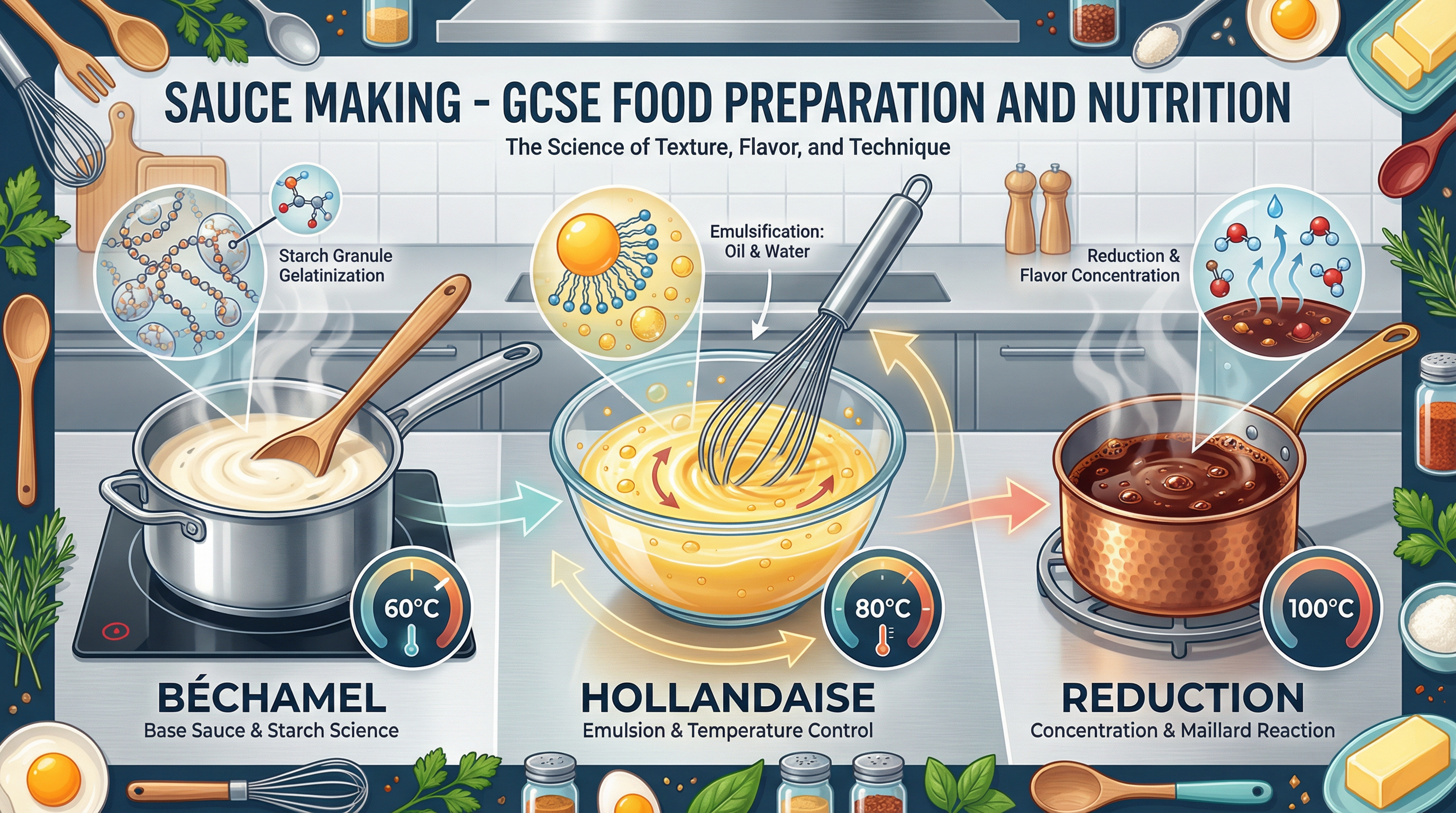

Sauce making is a fundamental culinary skill that forms a cornerstone of the AQA GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition specification. Beyond simply creating delicious accompaniments, this topic delves deep into the scientific principles that govern how ingredients interact. Examiners place a heavy emphasis on a candidate's ability to articulate the chemical and physical changes that occur during processes like gelatinisation, emulsification, and reduction. Understanding these concepts is not just about practical cooking; it is about demonstrating a robust knowledge of food science. This guide will equip you with the precise terminology, temperature points, and scientific explanations needed to excel in the exam. We will explore the functional properties of key ingredients, analyse common sauce faults from a scientific perspective, and provide worked examples that show you how to structure high-level responses. By mastering the content in this guide, you will be prepared to explain not just what happens in the pan, but why it happens at a molecular level, which is the key to unlocking the highest marks.

Key Scientific Principles

Gelatinisation: The Science of Starch Thickening

What it is: Gelatinisation is the process by which starch granules absorb liquid when heated, causing them to swell and burst, which in turn thickens the liquid. This is the primary method for thickening sauces like béchamel, velouté, and cheese sauce.

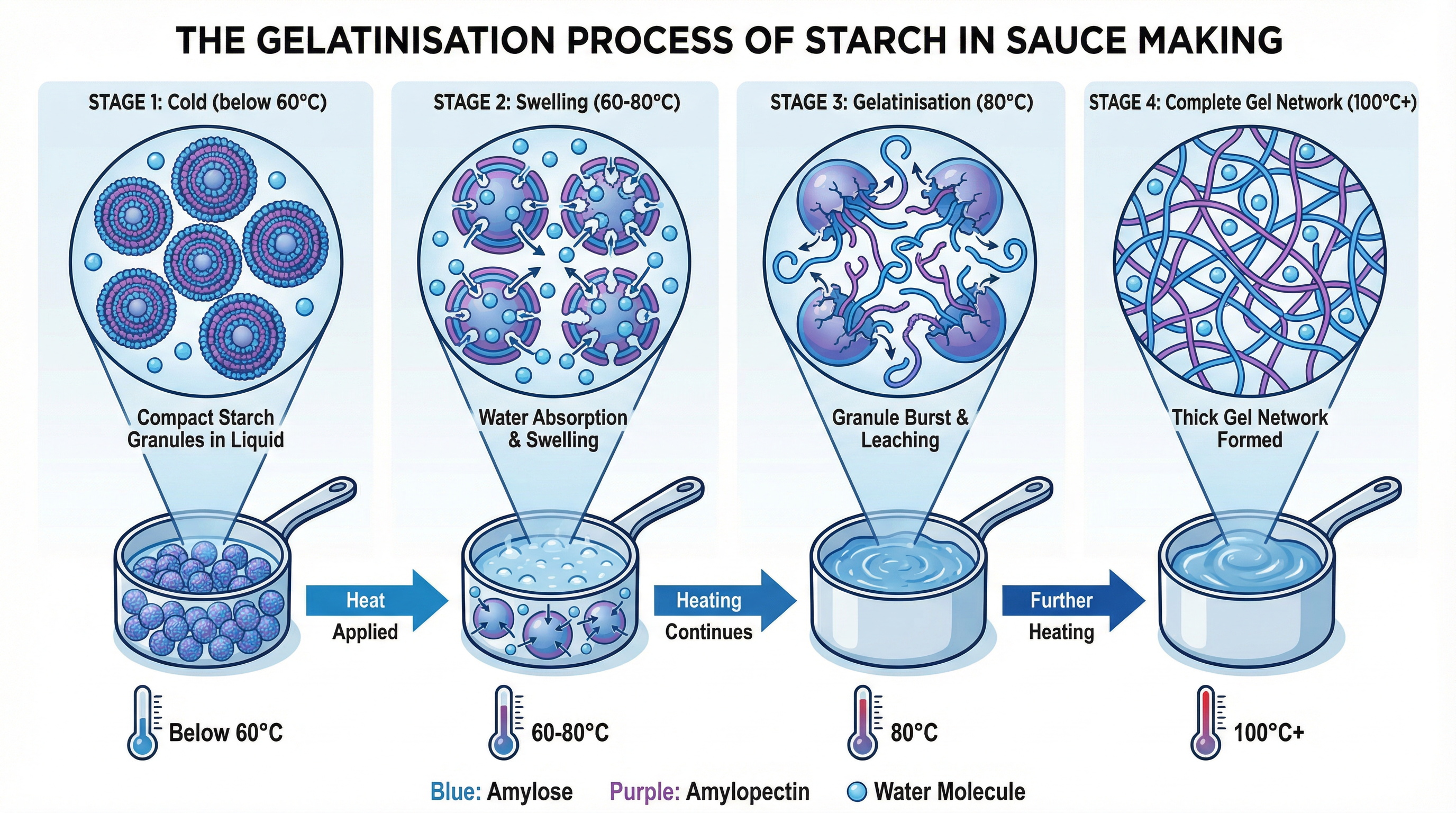

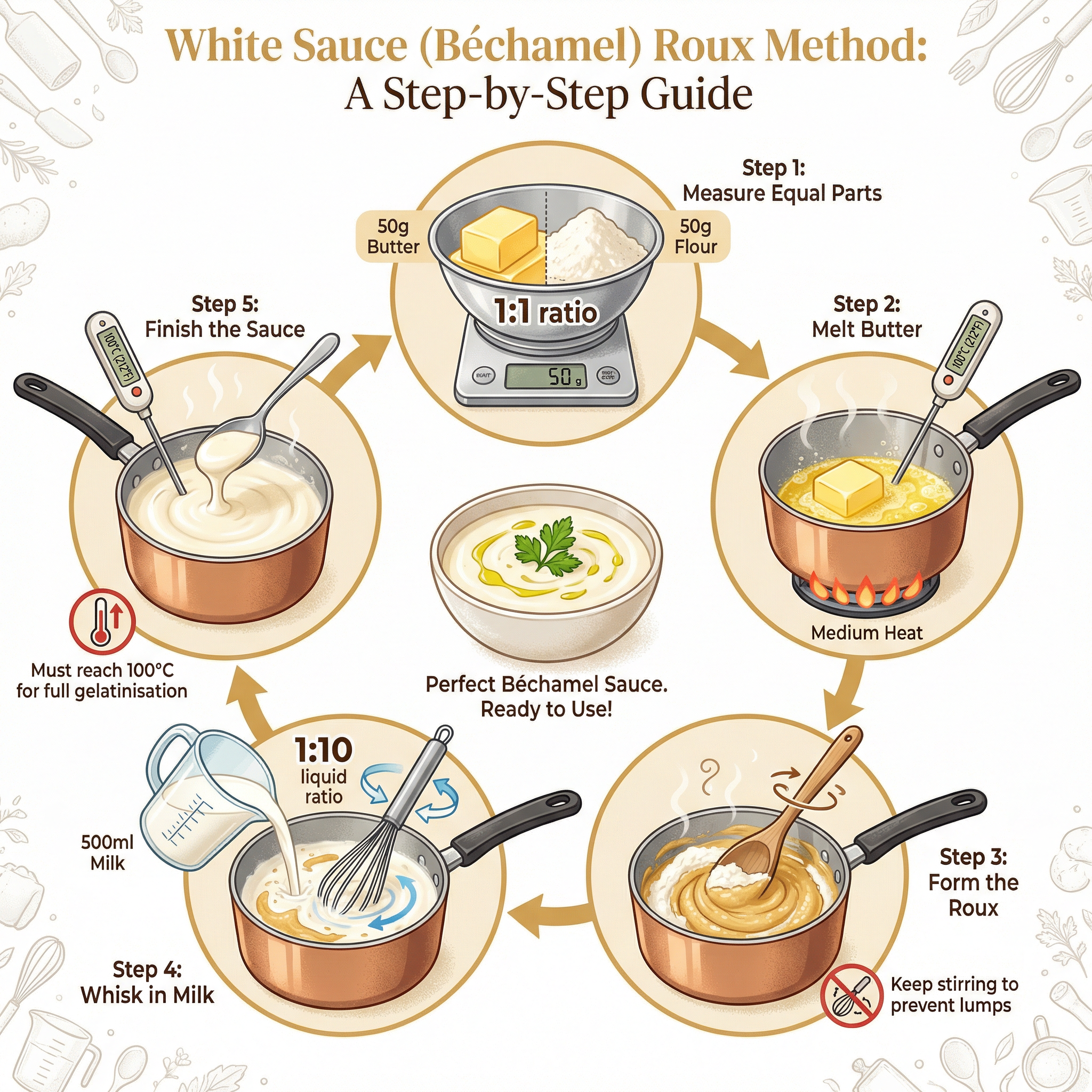

The Process Step-by-Step:

- Cold Liquid (Below 60°C): Starch granules (e.g., from flour) are suspended in the cold liquid but remain separate and do not absorb much water.

- Heating (60°C - 80°C): As the temperature rises to 60°C, the starch granules begin to absorb the surrounding liquid and swell significantly. Continuous stirring (agitation) is vital at this stage to prevent the granules from sticking together and forming lumps.

- Bursting Point (80°C): At approximately 80°C, the swollen granules rupture (burst), releasing long-chain starch molecules (amylose and amylopectin) into the liquid.

- Gel Formation (100°C): As the sauce reaches boiling point (100°C), these starch molecules form a complex three-dimensional network that traps water molecules. This network is what gives the sauce its thick, viscous, and smooth texture. The sauce must reach this temperature to achieve its maximum thickness and to cook out the raw taste of the flour.

Why it matters for the exam: Candidates must use precise temperatures and terminology. Simply stating that the sauce 'thickens with heat' will not receive many marks. Credit is given for explaining the swelling and bursting of starch granules and the formation of a starch-protein network. You must also be able to explain the importance of agitation.

Specific Knowledge: Know the key temperatures: 60°C (swelling starts), 80°C (granules burst), 100°C (gelatinisation complete). Remember the standard ratio for a roux-based sauce: 1 part fat : 1 part flour : 10 parts liquid (e.g., 50g butter, 50g flour, 500ml milk).

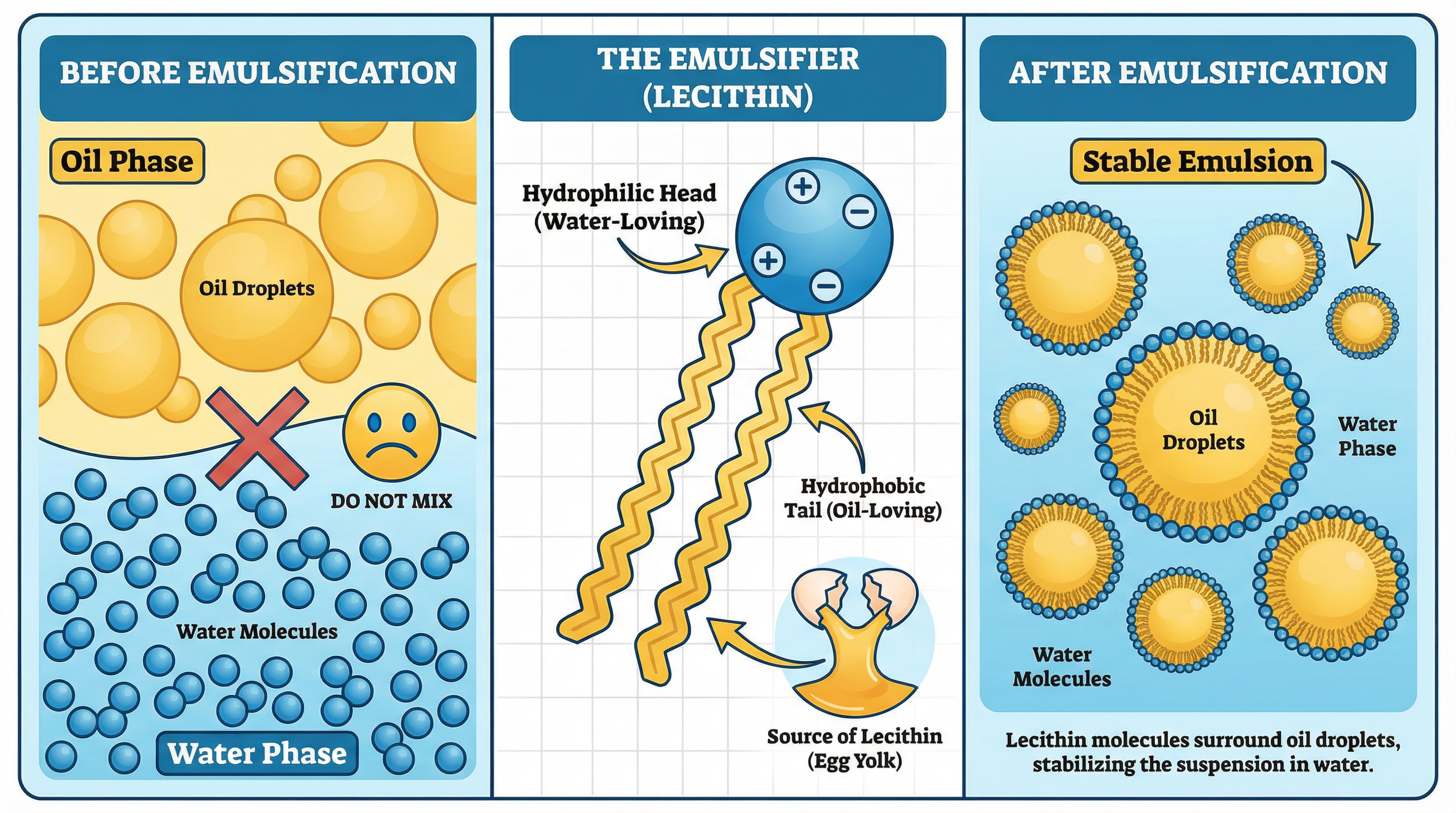

Emulsification: Making Oil and Water Mix

What it is: Emulsification is the process of dispersing one liquid (like oil) into another liquid with which it is immiscible (like water or vinegar). This is essential for creating stable sauces like mayonnaise, hollandaise, and vinaigrettes.

The Key Component - The Emulsifier: An emulsifier is a molecule that has a water-loving (hydrophilic) head and an oil-loving (hydrophobic) tail. In sauce making, the most common emulsifier is lecithin, which is found in egg yolks.

How it works:

- Immiscible Liquids: Oil and water naturally separate into layers because their molecules are not attracted to each other.

- Introducing the Emulsifier: When egg yolk is whisked with an acidic liquid (like lemon juice or vinegar), the lecithin molecules are dispersed.

- Creating the Emulsion: As oil is slowly added while whisking vigorously, the lecithin molecules arrange themselves around the tiny oil droplets. The hydrophobic tails point inwards, into the oil droplet, while the hydrophilic heads face outwards, into the surrounding watery liquid. This creates a stable suspension of oil droplets in water, preventing them from separating.

Why it matters for the exam: Marks are awarded for identifying lecithin as the emulsifier and explaining its dual hydrophilic/hydrophobic structure. You must be able to describe how this structure allows it to bond with both oil and water to create a stable emulsion. High-level responses will also discuss factors that can cause an emulsion to break (e.g., adding the oil too quickly, incorrect temperature).

Specific Knowledge: Lecithin (from egg yolk) is the key emulsifier. Know the difference between a temporary emulsion (like a vinaigrette, which separates on standing) and a permanent emulsion (like mayonnaise, which remains stable).

Reduction and Coagulation

Reduction: This is the process of simmering a sauce for a period to allow some of the water to evaporate. This has two main effects:

- Intensifies Flavour: As water is removed, the concentration of flavour compounds from the other ingredients (e.g., stock, wine, herbs) increases, resulting in a richer, more potent taste.

- Increases Viscosity: With less water, the sauce naturally becomes thicker.

Why it matters: You need to explain that flavour is intensified due to the increased concentration of flavour molecules.

Coagulation: This is the change in the structure of protein from a liquid to a solid or thicker liquid, brought about by heat, acid, or enzymes. In sauce making, this is most relevant to egg-based sauces like custard.

- The Process: When an egg-based sauce is heated, the protein chains unfold and then join together, trapping the liquid within their network. This causes the sauce to thicken and set.

- Temperature Control: This process is highly temperature-sensitive. If heated too quickly or to too high a temperature (above 85°C for egg proteins), the proteins will over-coagulate, squeezing out the trapped liquid and causing the sauce to curdle or scramble.

Why it matters: Candidates must differentiate between coagulation (protein-based) and gelatinisation (starch-based). For coagulation, you must stress the importance of gentle heating and temperature control to avoid curdling.

Second-Order Concepts

Causation

- Lumps in a Roux Sauce: Caused by adding liquid too quickly to the roux, or insufficient agitation (stirring/whisking). This prevents the starch granules from dispersing evenly before they begin to swell, causing them to clump together.

- A Split Mayonnaise: Caused by adding the oil too quickly, which overwhelms the emulsifier (lecithin) and prevents it from surrounding the oil droplets effectively. It can also be caused by the ingredients being too cold.

- A Curdled Custard: Caused by overheating the egg proteins (above 85°C). The proteins over-coagulate, tighten, and squeeze out the liquid they were holding, resulting in a grainy, separated texture.

Consequence

- Correct Gelatinisation: The consequence is a smooth, viscous, and stable sauce that coats the back of a spoon. The raw flour taste is eliminated.

- Stable Emulsification: The consequence is a thick, creamy, and glossy sauce where oil and water remain combined, providing a rich mouthfeel.

- Successful Reduction: The consequence is a sauce with a deep, concentrated flavour and a syrupy consistency, often seen in high-end restaurant dishes like a jus.

Change & Continuity

- Change: The primary change during sauce making is the transformation of state from liquid to a thicker, more viscous liquid or semi-solid gel. Ingredients undergo irreversible chemical and physical changes (e.g., starch granules bursting, proteins denaturing).

- Continuity: The base ingredients (fat, flour, liquid, eggs) and the fundamental scientific principles have remained the same for centuries. A béchamel made today follows the same principles of gelatinisation as one made 200 years ago.

Significance

Understanding the science of sauce making is significant because it moves a candidate from being a recipe-follower to a knowledgeable food scientist. It allows for the prediction of results, the diagnosis and correction of faults, and the creative adaptation of recipes for different dietary needs (e.g., using cornflour for a gluten-free diet) while still achieving the desired functional and sensory outcomes. This is a key skill assessed by AQA.

Dietary Adaptation Skills

Examiners frequently test a candidate's ability to adapt a standard sauce recipe for specific dietary needs. This requires you to justify your ingredient choices based on their functional performance.

| Dietary Need | Standard Ingredient to Replace | Replacement Ingredient | Scientific Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coeliac Disease (Gluten-Free) | Wheat Flour (in roux) | Cornflour, Arrowroot, or Potato Starch | These are all gluten-free starches that still undergo gelatinisation when heated with a liquid. They will swell and burst to thicken the sauce, performing the same functional role as wheat flour. |

| Lactose Intolerance | Cow's Milk (in béchamel) | Lactose-free milk, Soya milk, Oat milk | These liquids can still be used as the medium for gelatinisation. The starch granules will absorb these liquids just as they would cow's milk. Note that flavour and colour may be affected. |

| Vegan Diet | Butter (in roux), Milk, Eggs (in hollandaise) | Oil or vegan spread, Plant-based milk (soya, oat), Silken tofu or aquafaba (for emulsification) | For a roux, oil can replace butter as the fat. For emulsification, a different emulsifying agent is needed as lecithin from eggs cannot be used. This is a more complex adaptation requiring knowledge of alternative emulsifiers. |

| Low-Fat Diet | Butter/Fat (in roux) | Use a slurry (starch mixed with cold water) | To reduce fat, a roux can be avoided. A slurry of cornflour and water can be added to the hot liquid. The gelatinisation process will still occur, thickening the sauce without the need for fat. |