Study Notes

Overview

Bread making is a fundamental topic that beautifully marries biology, chemistry, and culinary skill. For AQA GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition, candidates are expected to move beyond a simple recipe and demonstrate a robust understanding of the scientific principles at play. This includes the functional properties of key ingredients, the biological action of yeast, and the chemical changes that occur during baking. Examiners are looking for precise, scientific language and a clear explanation of cause and effect. Mastering this topic is crucial as it frequently appears in a variety of question formats, from short-answer knowledge recall to extended-response evaluative tasks. This guide will break down the core concepts, provide exam-focused advice, and equip you with the scientific vocabulary needed to achieve top marks.

The Science of Ingredients

Flour: The Structural Foundation

What it is: The primary ingredient, typically strong plain flour (or bread flour), provides the structure of the bread.

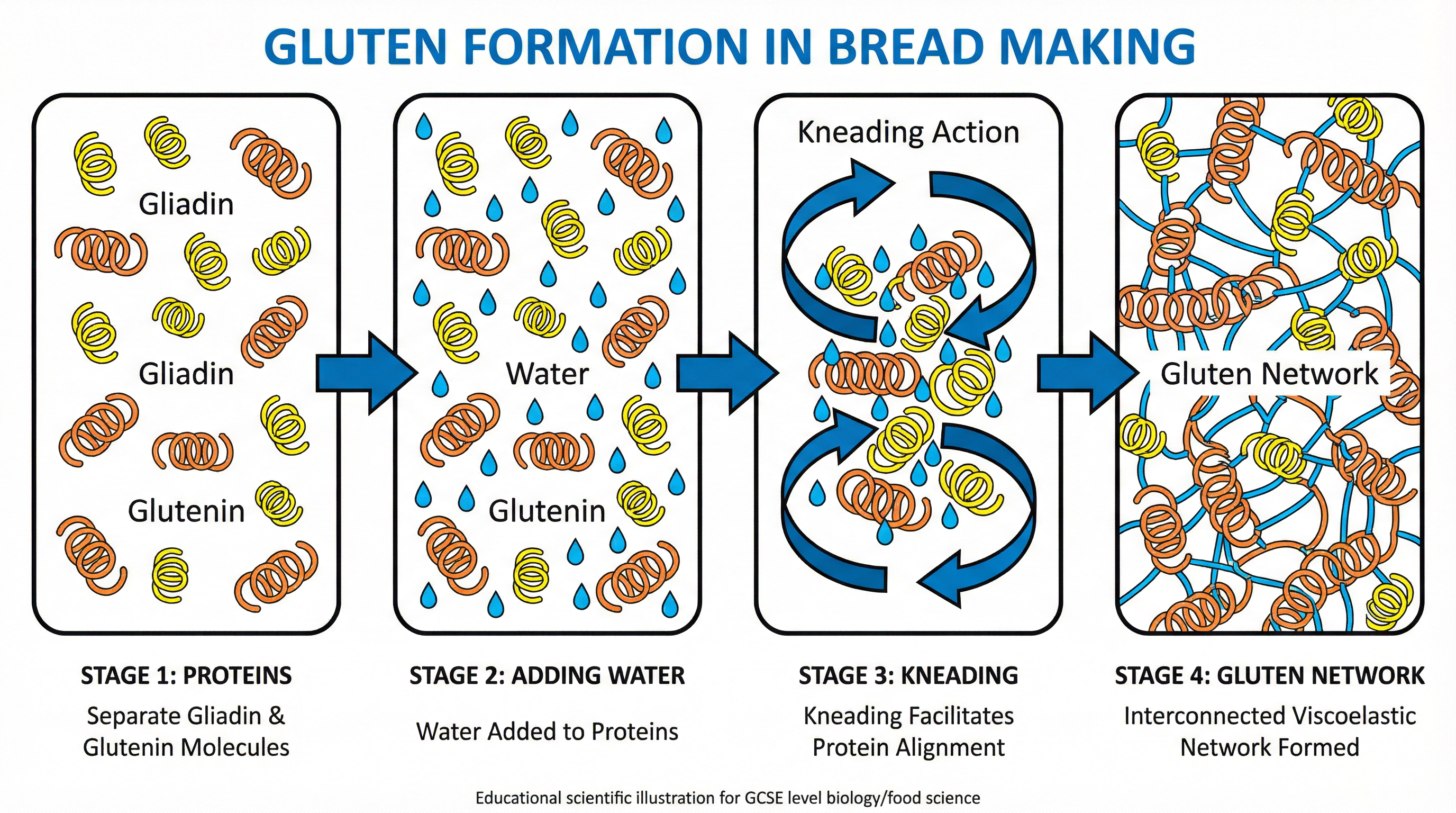

Why it matters: Strong plain flour has a high protein content (12-14%). These proteins, gliadin and glutenin, are essential for forming the gluten network. Credit is given for linking the flour type to its high protein content.

Specific Knowledge: Candidates must know the names of the two proteins. Using the term 'viscoelastic' to describe the gluten network will be rewarded.

Water: The Activator

What it is: Water hydrates the flour and activates the yeast.

Why it matters: Hydration allows the gliadin and glutenin proteins to combine and form gluten. The temperature of the water is critical for yeast activity. Examiners expect candidates to know the optimal temperature range.

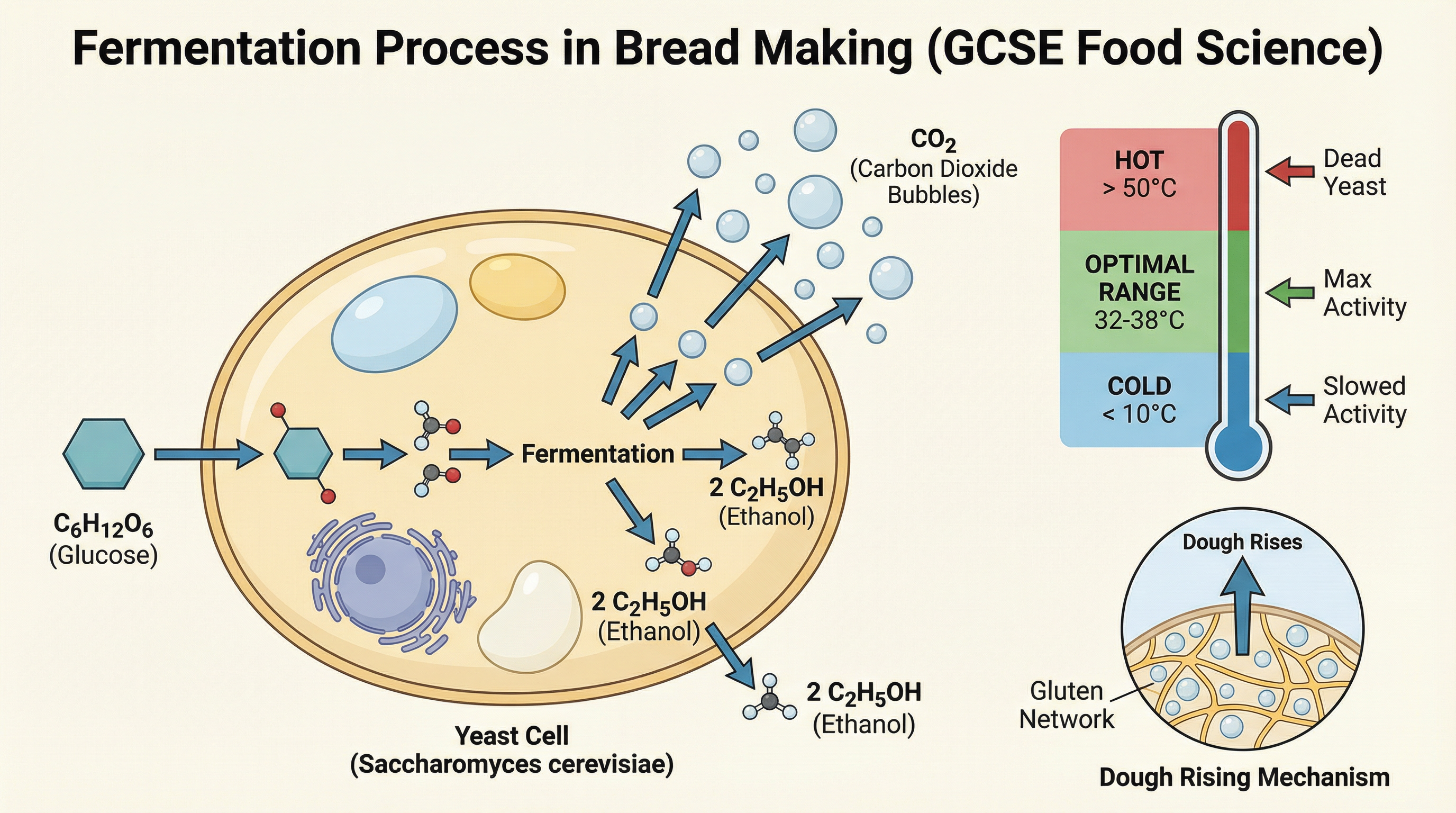

Specific Knowledge: The optimal temperature for yeast is 32-38°C. Water that is too hot (above 50°C) will kill the yeast, while cold water will significantly slow its activity.

Yeast: The Biological Raising Agent

What it is: A single-celled fungus (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) that acts as a biological raising agent.

Why it matters: Yeast performs anaerobic respiration (fermentation), converting glucose into carbon dioxide and ethanol. The CO2 gas is trapped by the gluten network, causing the dough to rise. This is a core concept that carries significant marks.

Specific Knowledge: The fermentation equation: Glucose → Carbon Dioxide + Ethanol. Candidates should not confuse yeast with chemical raising agents like baking powder.

Salt: The Controller

What it is: Sodium chloride, used in small quantities.

Why it matters: Salt plays a dual role. It adds flavour and, crucially, it controls the rate of fermentation by regulating the yeast's activity. It also strengthens the gluten network. A common mistake is to state that 'salt kills yeast' without qualification. While excessive salt or direct contact can inhibit or kill yeast, a small, controlled amount is beneficial.

Specific Knowledge: Salt should be around 2% of the flour weight. It should be mixed with the flour, not placed in direct contact with the yeast initially.

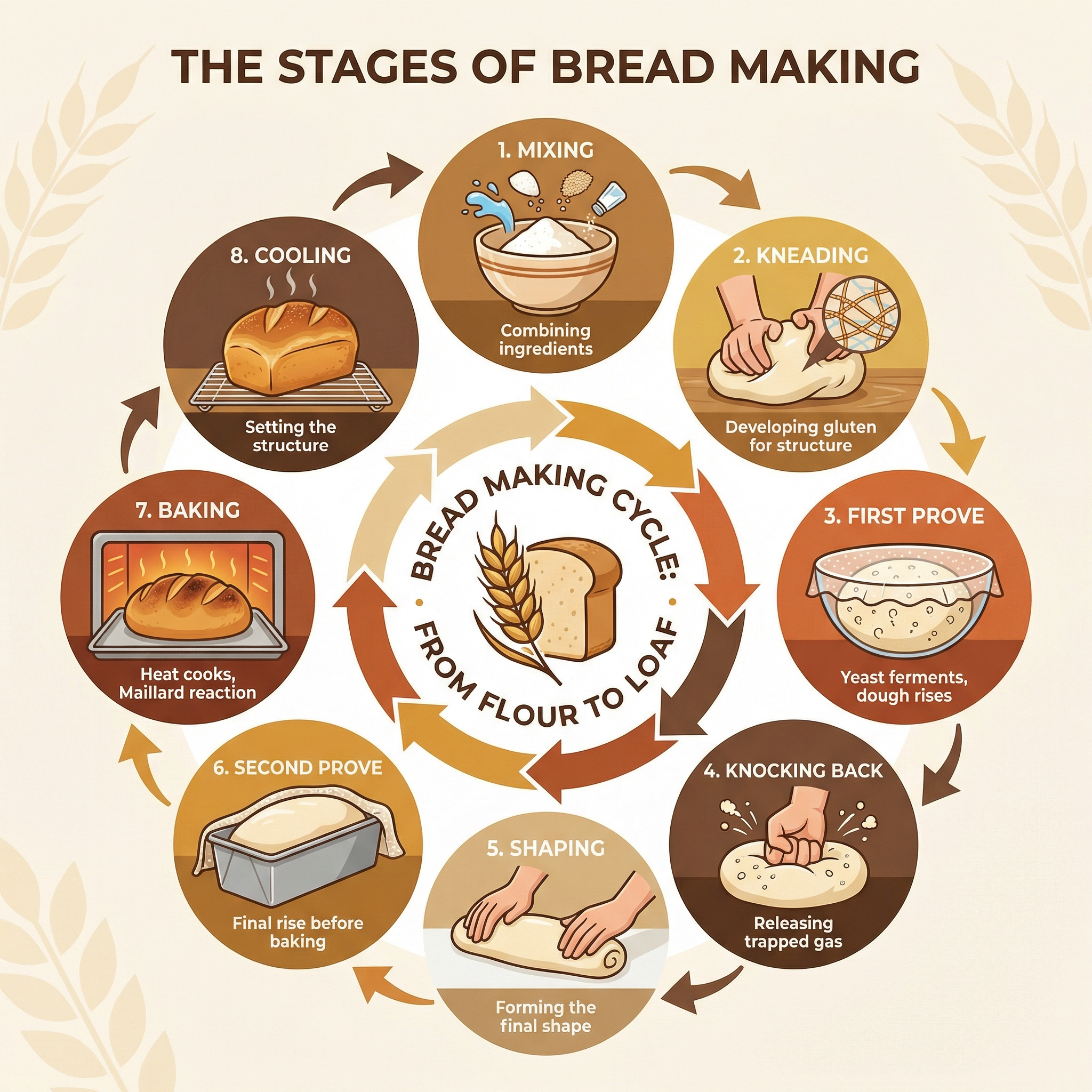

Key Processes in Bread Making

1. Gluten Formation

What happens: When water is added to flour and the dough is kneaded, the gliadin and glutenin proteins bond to form the gluten network. Kneading stretches and aligns these protein strands, creating a strong, stretchy, and elastic (viscoelastic) web.

Why it matters: This network is the framework of the bread. Its ability to stretch allows it to trap the CO2 produced by the yeast, leading to a well-risen loaf. Its elasticity helps the dough hold its shape.

2. Fermentation (Proving)

What happens: After kneading, the dough is left in a warm place to prove. During this time, the yeast ferments the sugars in the flour, releasing CO2 gas. The gas bubbles become trapped in the gluten network, causing the dough to increase in volume.

Why it matters: This is the primary leavening process. The length of proving time and the temperature directly impact the final texture and flavour of the bread. Over-proving can cause the gluten structure to collapse, while under-proving results in a dense loaf.

3. Baking: The Final Transformation

What happens: In the oven, a series of chemical and physical changes occur:

- Oven Spring: A rapid final rise as the CO2 gas expands in the heat.

- Yeast is Killed: At around 60°C, the yeast dies, and fermentation stops.

- Gluten Sets: The gluten network coagulates and sets, forming the permanent structure of the bread.

- Dextrinisation: The heat breaks down starch on the crust into simpler sugars, which then brown, creating a golden colour. This is a key term.

- Maillard Reaction: A chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars at high temperatures, which contributes to the brown colour and rich, savoury flavour of the crust.

Why it matters: Baking transforms the dough into an edible, digestible, and appealing product. Candidates must be able to distinguish between dextrinisation and the Maillard reaction to gain full credit. Describing the browning as 'caramelisation' is a common error.