Study Notes

Overview

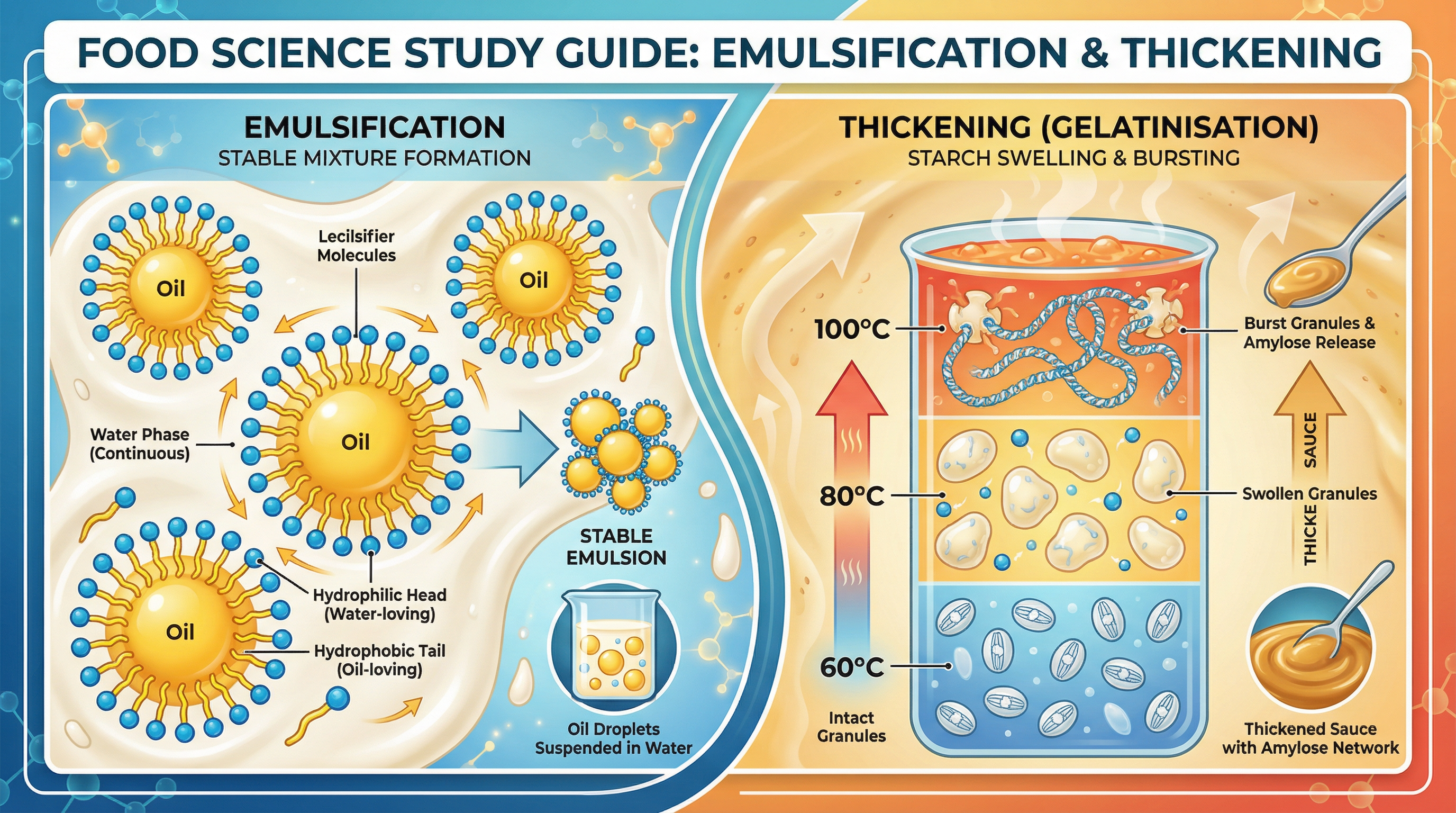

This study guide provides a comprehensive, exam-focused breakdown of two critical functional food properties for the AQA GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition specification: emulsification and thickening. AQA requires candidates to move beyond simple descriptions and demonstrate a precise understanding of the chemical and physical changes occurring at a molecular level. For emulsification, this means explaining how an emulsifying agent, such as lecithin, enables immiscible liquids like oil and water to mix and form a stable colloidal structure. For thickening, the focus is on the process of gelatinisation, where starch granules heated in a liquid swell, burst, and release amylose to create a viscous gel. Examiners award significant credit for the accurate use of scientific terminology and for structuring answers chronologically by temperature milestones. Mastering these concepts is not just about understanding how to make a sauce; it's about demonstrating the scientific knowledge (AO1) and application (AO2) that underpins culinary success, which together account for 60% of the total marks.

Key Processes: Emulsification

The Challenge: Immiscible Liquids

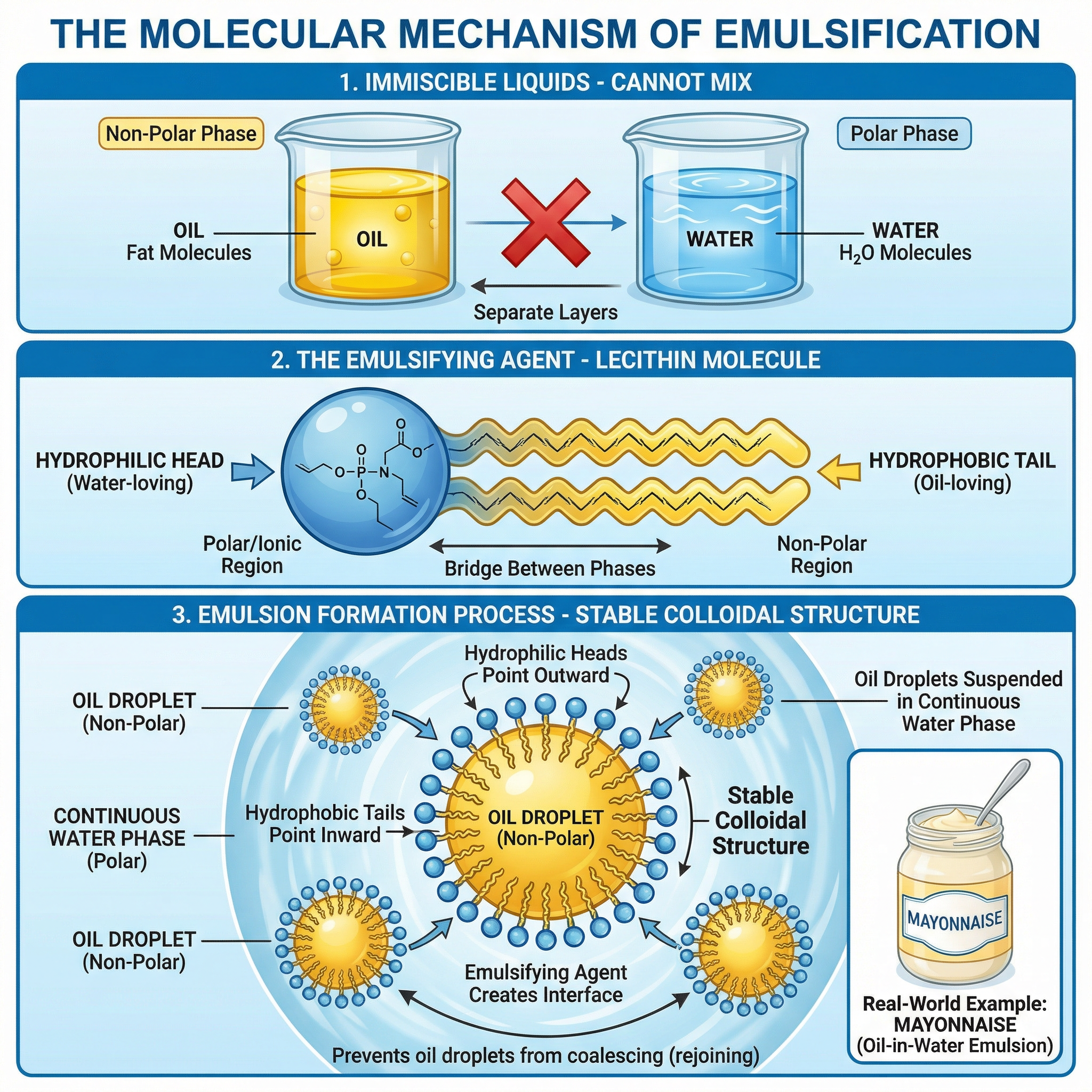

What happens: Oil (a non-polar liquid) and water (a polar liquid) do not naturally mix. When shaken together, they form a temporary suspension, but will quickly separate into layers upon standing. This is because the cohesive forces between water molecules are stronger than the adhesive forces between water and oil molecules.

Why it matters: Many fundamental food products, from mayonnaise and hollandaise sauce to salad dressings and even milk, are emulsions. Without a method to stabilize these mixtures, they would be unusable.

The Solution: The Emulsifying Agent

What happened: An emulsifying agent is a molecule that has both a water-loving (hydrophilic) part and an oil-loving (hydrophobic) part. The classic example for your exam is lecithin, found in egg yolks.

- Hydrophilic Head: This part of the molecule is polar and is attracted to water.

- Hydrophobic Tail: This part is non-polar and is attracted to oil.

When an emulsifier is added to an oil and water mixture and agitated (e.g., by whisking), the emulsifier molecules arrange themselves at the interface between the oil droplets and the surrounding water. The hydrophobic tails point into the oil droplet, and the hydrophilic heads point out into the water. This forms a protective layer around each oil droplet, preventing them from clumping together (coalescing) and creating a stable colloidal structure known as an emulsion.

Specific Knowledge: Candidates must be able to draw and label a diagram showing the orientation of lecithin molecules around an oil droplet in an oil-in-water emulsion. Credit is given for correctly identifying the hydrophilic head and hydrophobic tail.

Key Processes: Thickening (Gelatinisation)

The Science of Starch

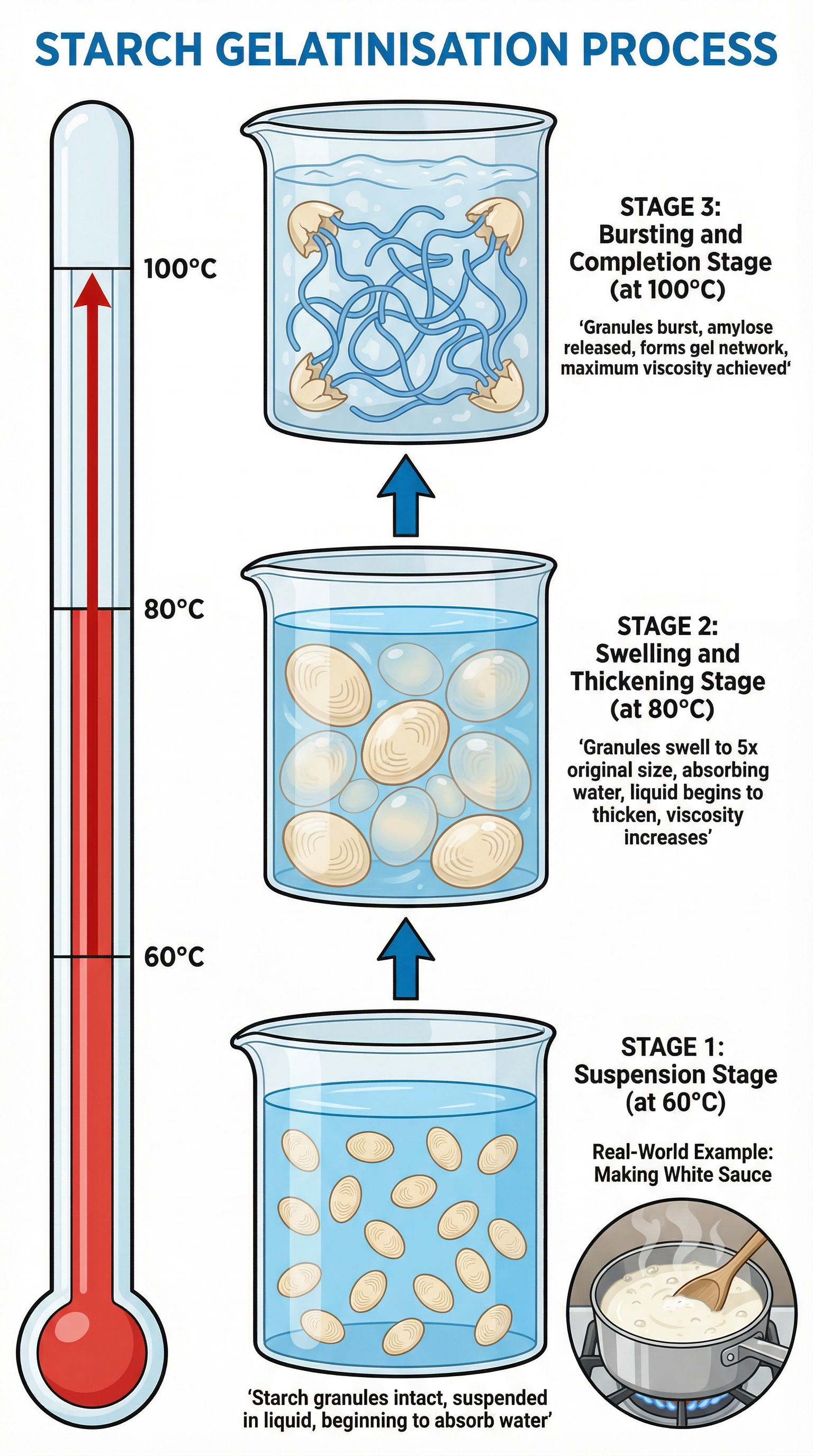

What happened: Gelatinisation is the process where starch granules absorb liquid in the presence of heat, causing them to swell and thicken the liquid. This is fundamental to making sauces, gravies, and custards.

Why it matters: It is a primary method of thickening in cooking. Understanding the temperature-specific stages is crucial for controlling the texture of a final product and for achieving high marks in the exam.

The Three Critical Stages of Gelatinisation

Examiners expect candidates to describe this process chronologically, referencing the key temperature points.

- Suspension (Up to 60°C): Starch granules are suspended in cold liquid. They are insoluble and remain separate. No thickening occurs.

- Swelling & Thickening (60°C - 80°C): As the liquid is heated, the starch granules begin to absorb water and swell significantly, up to five times their original size. The liquid begins to thicken as the swollen granules take up more space, increasing the viscosity.

- Bursting & Completion (80°C - 100°C): At around 80°C, the granules are fully swollen. As the temperature approaches boiling point (100°C), the granules burst and release long-chain starch molecules, primarily amylose, into the surrounding liquid. These amylose molecules form a complex three-dimensional network that traps the water molecules, resulting in a thick, viscous gel. This is the point of maximum thickness.

Specific Knowledge: Candidates must state that the granules burst to release amylose. Simply stating that they swell is insufficient for top marks. Mentioning the term syneresis (the weeping of liquid from a gel, often caused by overheating or over-stirring which breaks the amylose network) will also gain credit.