Study Notes

Overview

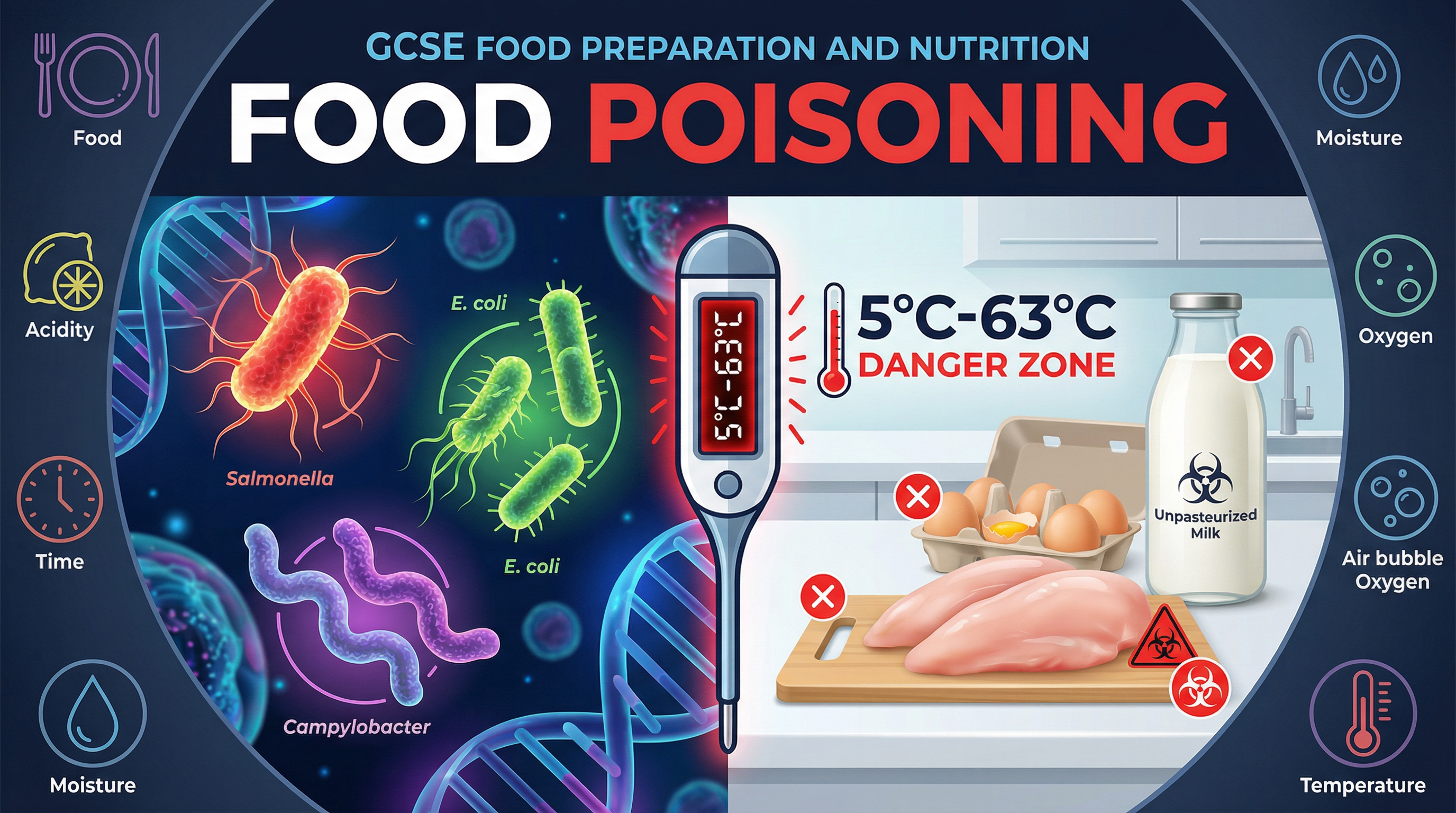

Food poisoning is a critical area of study within the AQA GCSE specification, carrying significant weight in the final examination. A thorough understanding is essential not just for food safety in practice, but for demonstrating the scientific knowledge that examiners reward. This guide covers the core principles of food microbiology, focusing on the conditions that promote the growth of pathogenic bacteria and the preventative measures used to control them. Candidates are expected to move beyond common sense and apply precise scientific terminology and data, such as the critical temperatures for food storage and cooking. Marks are awarded for linking specific bacteria like Salmonella and Campylobacter to their high-risk food sources and for explaining the implications of control measures, such as how correct refrigeration temperatures make bacteria dormant, rather than killing them. This topic requires a detailed, analytical approach to achieve the highest grades.

Key Pathogenic Bacteria

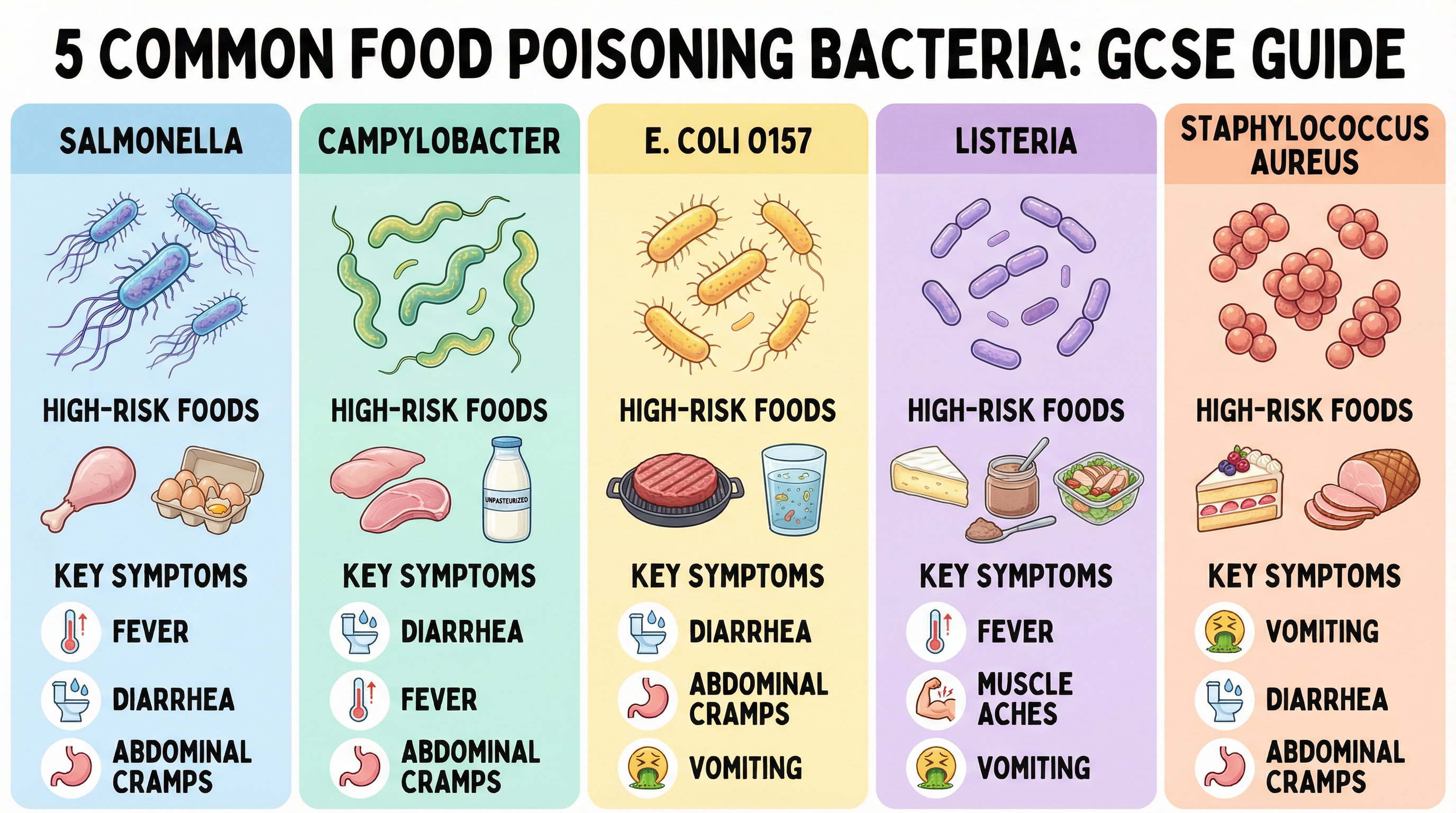

Examiners require candidates to have specific knowledge of the most common pathogenic bacteria responsible for food poisoning in the UK. Credit is given for linking the bacterium to its common food sources, symptoms, and onset times.

Salmonella

- High-Risk Foods: Raw and undercooked poultry (chicken, turkey), eggs, and products containing raw eggs (e.g., homemade mayonnaise).

- Mechanism: Salmonella bacteria live in the gut of many farm animals and can contaminate food during slaughter or processing. They are destroyed by thorough cooking.

- Symptoms: Fever, diarrhoea, and abdominal cramps. Onset time is typically 12-72 hours.

- Examiner Note: Candidates must specify that cooking to a core temperature of 75°C is required to kill Salmonella.

Campylobacter

- High-Risk Foods: Raw and undercooked poultry, unpasteurised milk, and contaminated water.

- Mechanism: This is the most common cause of food poisoning in the UK. It spreads easily via cross-contamination, for example, from washing raw chicken under a tap.

- Symptoms: Diarrhoea (often bloody), abdominal pain, and fever. Onset time is 2-5 days.

- Examiner Note: High marks are awarded for explaining cross-contamination prevention, such as using separate chopping boards for raw and cooked foods.

E. coli O157

- High-Risk Foods: Undercooked beef (especially minced beef), unpasteurised milk, and contaminated salad vegetables or water.

- Mechanism: A particularly nasty strain that can cause serious illness. It lives in the gut of cattle and can be transferred to the surface of meat during processing.

- Symptoms: Severe abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhoea. Can lead to kidney failure.

- Examiner Note: Credit is given for linking E. coli to the importance of cooking minced meat products thoroughly until the juices run clear and there is no pink meat visible.

Listeria monocytogenes

- High-Risk Foods: Chilled, ready-to-eat foods such as pâté, soft cheeses (e.g., Brie, Camembert), and smoked salmon.

- Mechanism: Unlike many other bacteria, Listeria can grow at refrigeration temperatures (below 5°C). It is particularly dangerous for vulnerable groups like pregnant women.

- Symptoms: Flu-like symptoms, fever, and muscle aches. Can cause miscarriage in pregnant women.

- Examiner Note: Candidates should highlight the importance of adhering to 'use-by' dates and maintaining a fridge temperature of 0-5°C.

Staphylococcus aureus

- High-Risk Foods: Foods that are handled extensively and not subsequently cooked, such as cold cooked meats, cream cakes, and sandwiches.

- Mechanism: The bacteria are carried on the skin, hair, and in the noses of up to 50% of people. They produce toxins that are not destroyed by cooking.

- Symptoms: Rapid onset (1-6 hours) of severe vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhoea.

- Examiner Note: This is a key example of food poisoning caused by a toxin. Marks are awarded for explaining the importance of high standards of personal hygiene to prevent contamination.

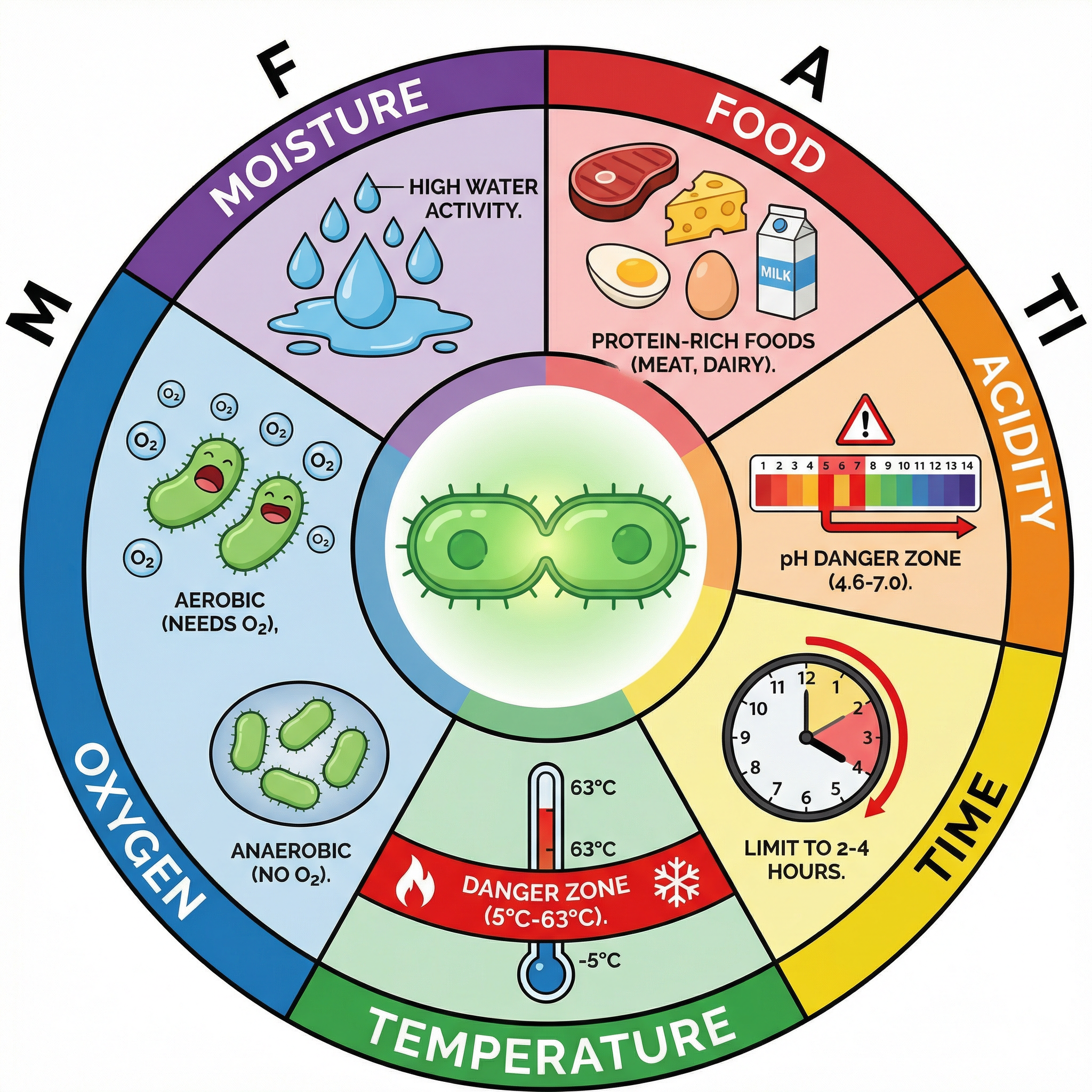

Conditions for Bacterial Growth: FAT TOM

To secure top marks, candidates must be able to explain the six conditions that bacteria need to multiply. The mnemonic FAT TOM is an essential tool for structuring answers.

- Food: Bacteria require nutrients to grow, especially high-protein foods like meat, fish, poultry, eggs, and dairy products.

- Acidity: Bacteria prefer neutral or low-acidity environments. The pH 'danger zone' is between 4.6 and 7.0. Preservation methods like pickling use acid (vinegar) to make the environment hostile to bacteria.

- Time: In ideal conditions, bacteria can multiply (through binary fission) every 20 minutes. Food left in the danger zone for more than 2-4 hours can become unsafe.

- Temperature: This is the most critical factor. The temperature danger zone is 5°C to 63°C. Within this range, bacteria multiply rapidly. Freezing (below 0°C) makes bacteria dormant, while cooking to a core temperature of 75°C kills most types.

- Oxygen: Some bacteria are aerobic (require oxygen), while others are anaerobic (do not require oxygen). This is why vacuum packing can be an effective preservation method.

- Moisture: Bacteria need water to grow. This is measured by 'water activity'. Drying foods (like beef jerky or dried fruit) removes moisture and inhibits bacterial growth.

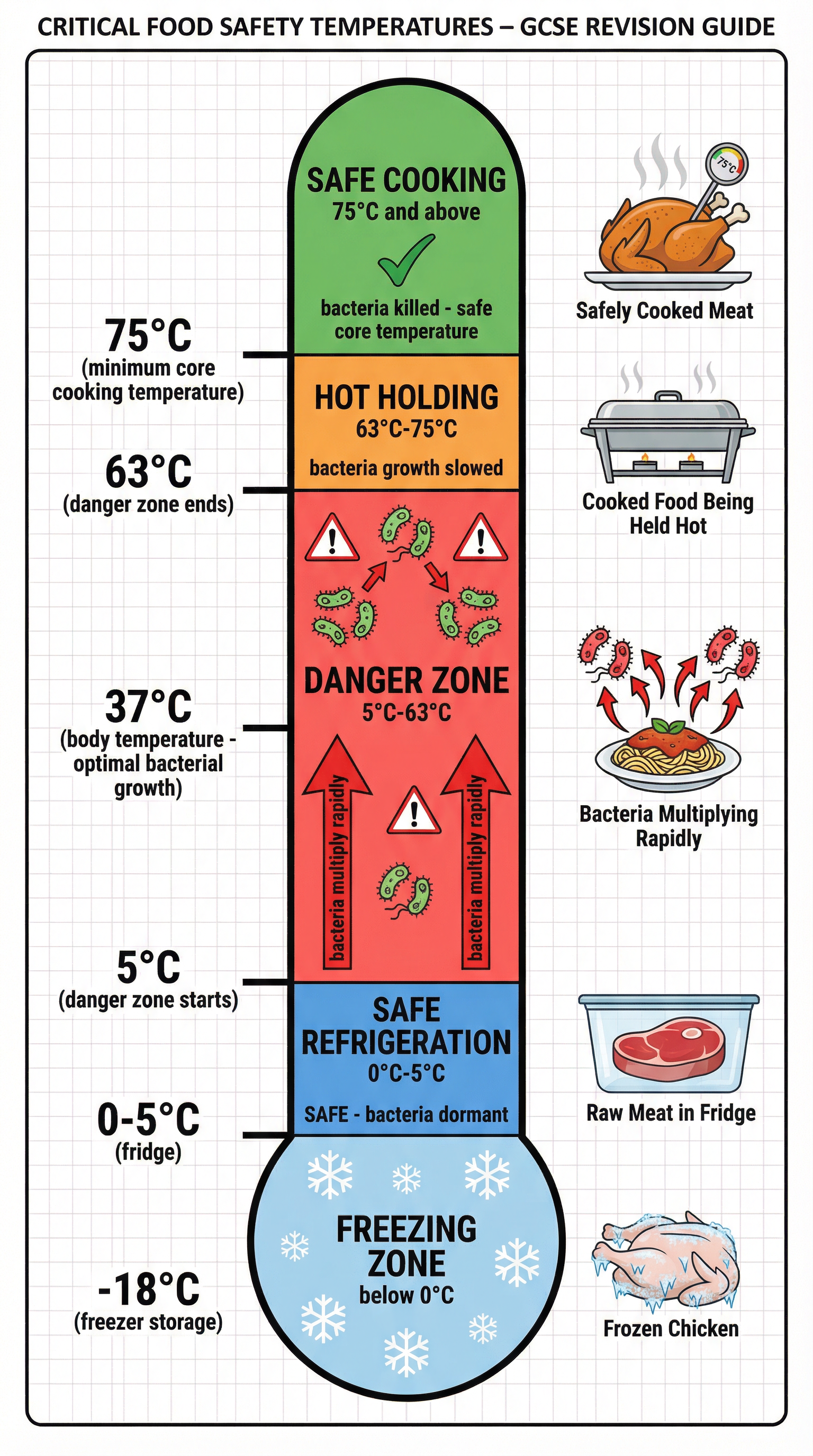

Critical Temperature Control

Examiners expect precise temperature values in answers relating to food safety. Vague statements like 'cook food well' will not receive full credit.

- Freezer Temperature: -18°C. At this temperature, bacteria are dormant.

- Fridge Temperature: 0°C to 5°C. At this temperature, the growth of most pathogenic bacteria is slowed down significantly. Listeria is a key exception.

- The Danger Zone: 5°C to 63°C. This is the range where bacteria multiply most rapidly. Food should be kept out of this zone as much as possible.

- Hot Holding Temperature: Above 63°C. Food being kept hot (e.g., on a buffet) must be held above this temperature to prevent bacterial growth.

- Core Cooking Temperature: 75°C. Food must reach this internal temperature for at least 30 seconds (or an equivalent time/temperature combination) to ensure pathogenic bacteria are killed. A food probe is used to check this.