Study Notes

Overview

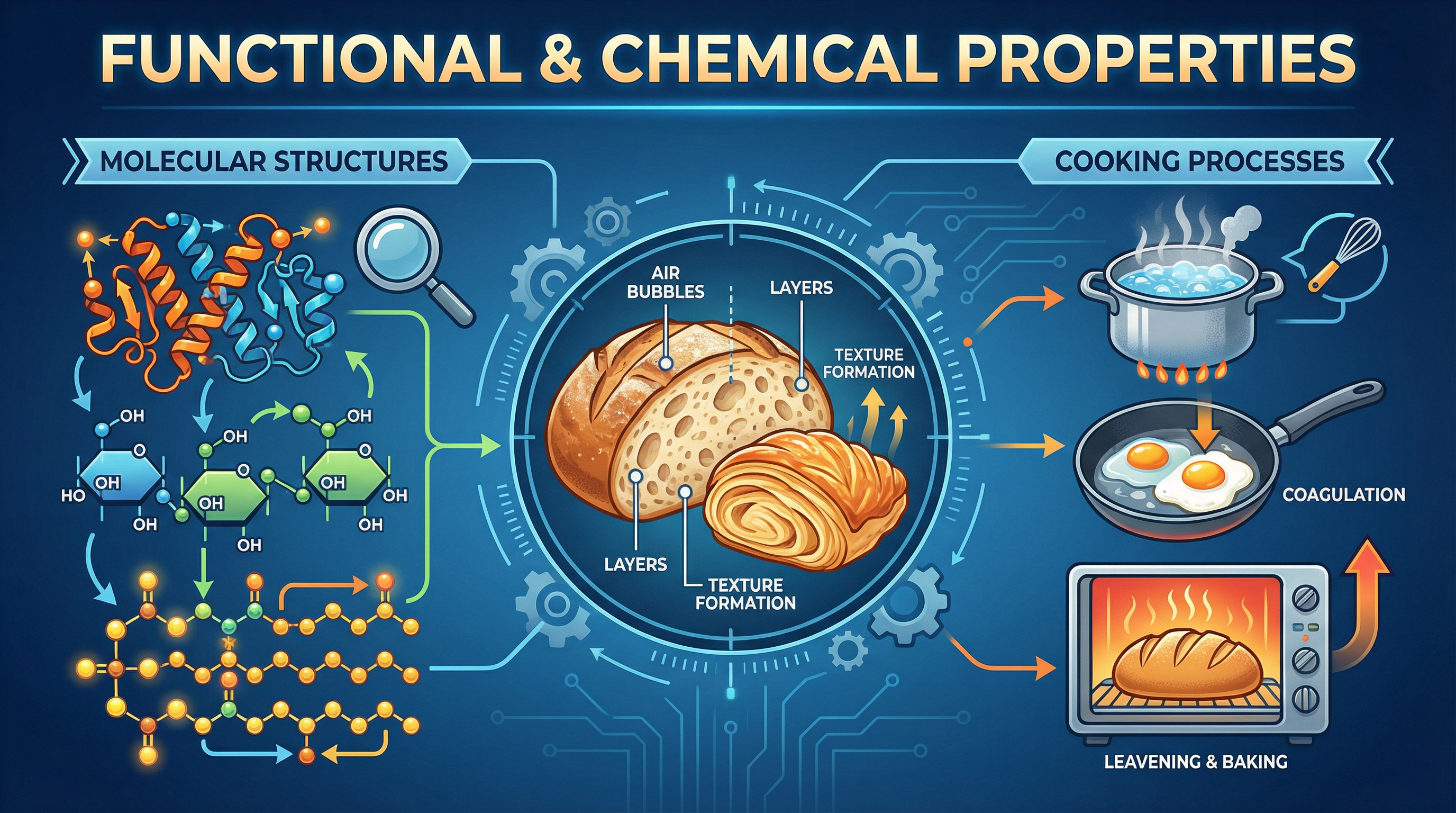

Welcome to the definitive guide for AQA GCSE Food Preparation and Nutrition, Section 3.2: Functional and Chemical Properties of Ingredients. This section is a cornerstone of the specification, carrying significant weight in your final exam (AO1: 40%, AO2: 40%). Examiners expect candidates to demonstrate a precise, scientific understanding of how proteins, carbohydrates, and fats behave during food preparation. This is not just about knowing recipes; it is about understanding the 'why' behind them. You will be expected to use accurate terminology to explain processes like coagulation, gelatinisation, and dextrinisation, and to link these chemical changes to the final sensory qualities of a dish. This guide will equip you with the detailed knowledge and exam technique required to analyse, explain, and evaluate these properties with confidence, ensuring you can provide the level of detail that examiners reward with the highest marks.

Key Chemical Processes

Protein: Denaturation and Coagulation

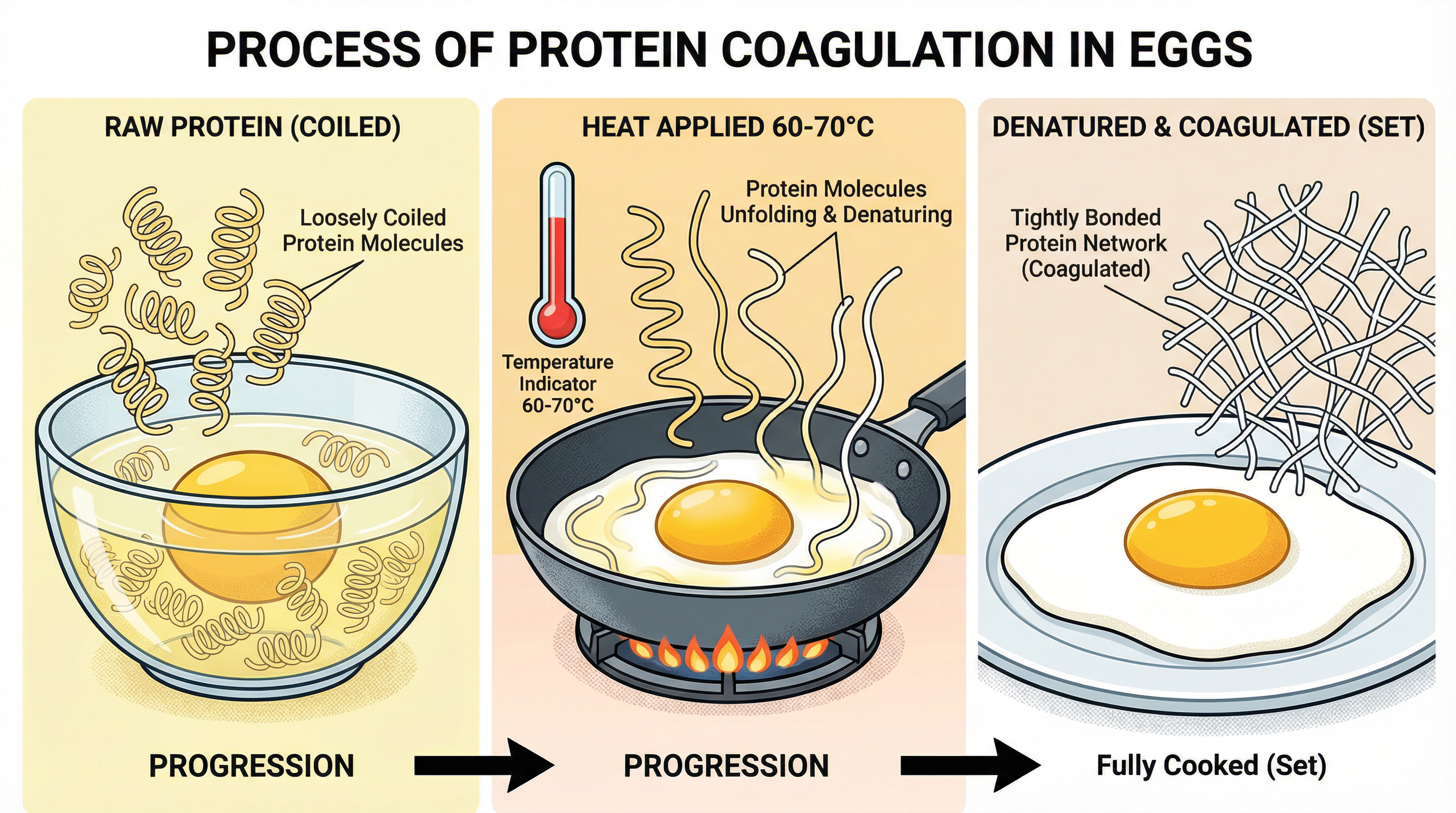

What happens: Proteins are large, complex molecules made of amino acids, initially folded into a specific 3D structure. The application of heat, acid, or mechanical agitation (like whisking) causes these proteins to unfold and lose their structure. This irreversible process is called denaturation. Following denaturation, the unfolded protein strands can then bond with each other to form a solid, three-dimensional network, trapping water. This is coagulation.

Why it matters: Coagulation is fundamental to cooking. It is responsible for the setting of eggs in a quiche, the firming of meat during cooking, and the creation of cheese from milk. Marks are awarded for explaining this two-stage process clearly.

Specific Knowledge: Candidates must know the critical temperature for egg protein coagulation: 60°C - 70°C. For example, when making a baked egg custard, the egg proteins denature and coagulate within this temperature range to set the liquid into a smooth, solid gel.

Carbohydrates: Gelatinisation, Dextrinisation, and Caramelisation

1. Starch Gelatinisation

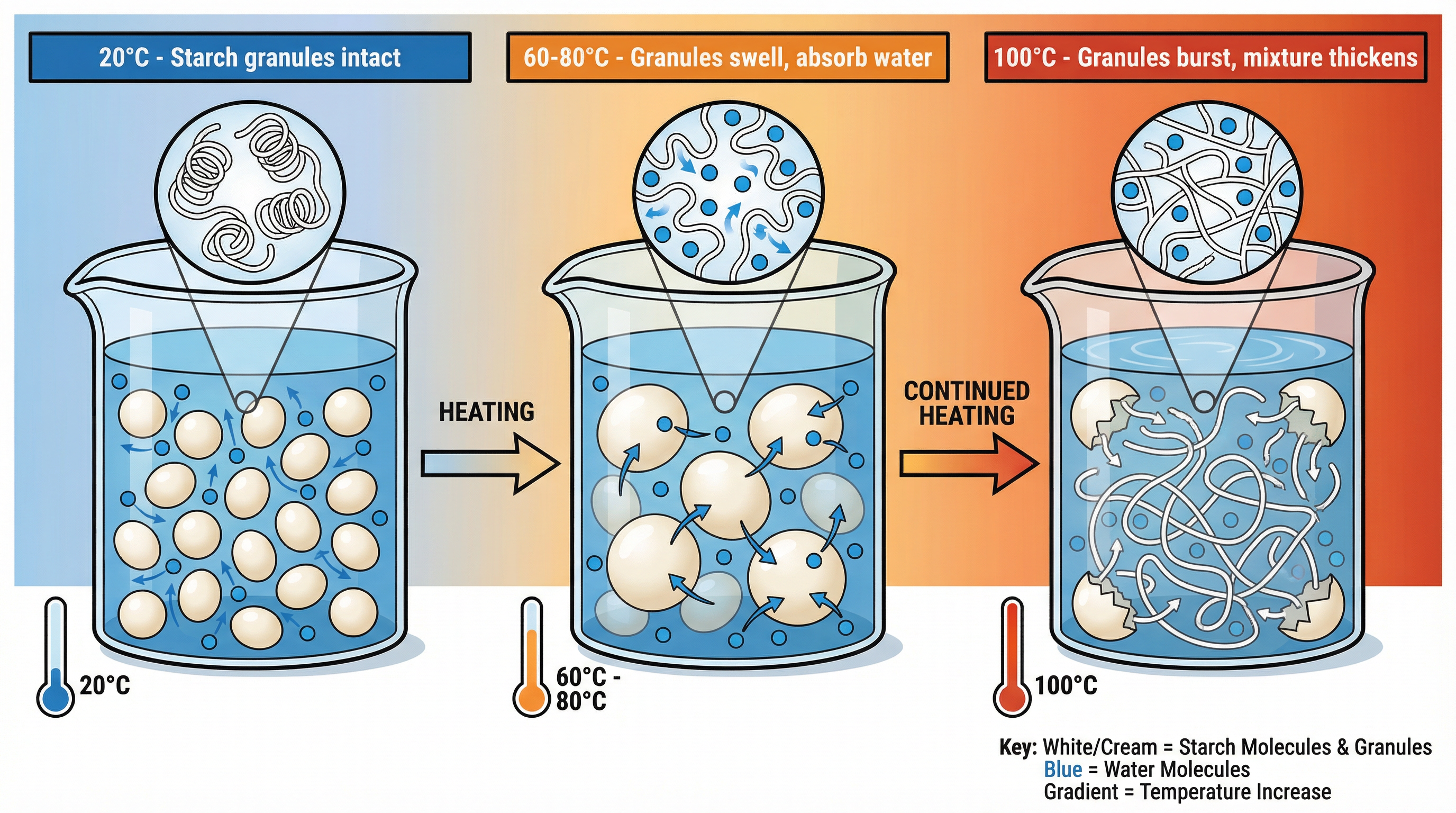

What happens: Starch granules are insoluble in cold water. When heated in the presence of a liquid, they begin to absorb water and swell from around 60°C. At approximately 80°C, the granules rupture, releasing long starch molecules (amylose and amylopectin) that form a network, trapping the water and thickening the liquid. The mixture becomes a viscous gel.

Why it matters: This process is essential for thickening sauces (e.g., a béchamel), baking cakes, and cooking pasta and rice. Credit is given for explaining the role of both heat and liquid.

Specific Knowledge: Key temperature range: 60°C - 100°C. Candidates should be able to describe the stages of swelling and bursting to explain the thickening process fully.

2. Dextrinisation

What happens: When starchy foods like bread or flour are subjected to dry heat, the long starch molecules break down into smaller molecules called dextrins. This chemical change results in the characteristic browning and development of a slightly sweet, nutty flavour.

Why it matters: This is the process responsible for the golden-brown crust on bread, the browning of toast, and the colour of baked goods. It is a common point of confusion with caramelisation, and distinguishing them is key.

Specific Knowledge: This is a reaction involving starch and dry heat. No sugar is required. For example, when a slice of bread is toasted, the surface starch dextrinises, creating a brown, crisp layer.

3. Caramelisation

What happens: Caramelisation is the oxidation of sugar when heated to high temperatures (around 160°C - 180°C). The sugar melts, boils, and breaks down, forming hundreds of new compounds that create a complex, sweet, nutty flavour and a rich brown colour.

Why it matters: This process is used to make caramel sauce, spun sugar, and contributes to the flavour of many baked goods and roasted vegetables (like onions and carrots).

Specific Knowledge: This involves sugar and high heat. Candidates must know the approximate temperature and be able to differentiate it clearly from dextrinisation.

Fats: Emulsification and Aeration

1. Emulsification

What happens: Fats (oils) and water do not naturally mix. An emulsion is a stable mixture of these two immiscible liquids, achieved with the help of an emulsifier. The emulsifier molecule has a hydrophilic (water-loving) head and a hydrophobic (water-hating) tail. It arranges itself at the boundary between the oil and water, preventing them from separating.

Why it matters: Emulsification is crucial for making sauces like mayonnaise and hollandaise, as well as salad dressings and milk.

Specific Knowledge: The primary emulsifier in egg yolk is lecithin. Candidates should be able to explain how its molecular structure allows it to stabilise oil-in-water or water-in-oil emulsions.

2. Aeration

What happens: Aeration is the process of incorporating air into a mixture. Fats like butter and margarine are effective at trapping air bubbles, especially when creamed with sugar. The fat forms a plastic-like network that holds the air.

Why it matters: This process is vital for the light, open texture of cakes and biscuits. The trapped air expands upon heating, acting as a raising agent.

Specific Knowledge: The property of fat that allows it to be creamed is its plasticity. Credit is given for explaining that creaming fat and sugar creates a foam of small air bubbles held within the fat, which provides leavening.

Raising Agents

What happens: Raising agents introduce gas into a mixture, which expands when heated, causing the product to rise and develop a light, open texture.

Why it matters: Essential for bread, cakes, scones, and pastries. Candidates must be able to compare and contrast the different types.

Specific Knowledge: There are three types:

- Chemical: Bicarbonate of soda (alkali) reacts with an acid (like buttermilk or lemon juice) in the presence of moisture to produce carbon dioxide (CO2). Baking powder is a pre-mixed version containing both acid and alkali.

- Biological: Yeast is a single-celled fungus that feeds on sugar in a warm, moist environment, producing CO2 and alcohol through fermentation.

- Mechanical: Air is incorporated by whisking, sieving, or creaming (aeration). Steam is produced when a mixture with a high water content is heated rapidly in a hot oven (e.g., choux pastry, Yorkshire puddings).

{{asset:raising_agents_comparison.png